Appearances can be deceptive. Numerous Iowa corn fields are turning into vineyards.

Appearances can be deceptive. Numerous Iowa corn fields are turning into vineyards.

Midwestern Magic: Iowa’s Home-Grown Innovators

by Clark Smith

March 19, 2009

ould there be a more unlikely spot for me to ask you wine lovers to cast a gaze upon? Hey, a scant seven years ago, Iowa was home to only a dozen wineries, making mostly fruit wines. But in 2009 we can count 80 wineries producing 600 wines. (Lest those numbers invite comparison to California in 1970, we are still only talking a state-wide total of 100,000 cases.) Yet for the adventurous connoisseur, those ranks include some of the most interesting, well made, and flat out delicious wines on the continent.

ould there be a more unlikely spot for me to ask you wine lovers to cast a gaze upon? Hey, a scant seven years ago, Iowa was home to only a dozen wineries, making mostly fruit wines. But in 2009 we can count 80 wineries producing 600 wines. (Lest those numbers invite comparison to California in 1970, we are still only talking a state-wide total of 100,000 cases.) Yet for the adventurous connoisseur, those ranks include some of the most interesting, well made, and flat out delicious wines on the continent.

Yeah, right. But hear me out. The can-do attitude of Iowa’s new generation of farmer vintners has deep regional roots. The Amana Colony, once reclusive pioneers seeking a quiet corner in which to build their utopia, started growing wine in 1852. They emerged a century later as a household synonym for quality, innovative kitchen appliances, including the first microwave, that famous technical leap of questionable culinary pedigree. Iowans have always been up for an out-of-the-box technical challenge. The corn-into-fuel homegrown energy scheme for decreasing our foreign oil dependence has set convention on its ear, sparking debate among both physicist and politicians.

And there you have it. Ingenious, home-grown, and fighting for acceptance. Yet we have all learned to respect Iowa’s smarts. This is where America turns every four years for the intense populist grilling of our aspiring Presidents. Now Iowa again demands our attention, this time from the connoisseur.

The renowned Maytag Farms Blue Cheese is an Iowa appellation classic.

Yet outside Snootsville, local wineries were quietly building a following. Trouble was that there was no legal way to distribute. So in 2001, the Iowa legislature took action, passing the Native Winery Bill, which provided for direct sales to consumers and earmarked taxes for Iowa State University to teach them how to make wines worth crowing about. The minute the rules changed, Iowa’s winery boom exploded.

Imported Sage Makes Wines That Age

I.S.U.’s next move? Kidnap Murli Dharmadhikari. Say what? Well, folks, just ask any Midwest winemaker from Missouri to Tennessee, and they will tell you that the most important enologist in America is Murli D., or Murli Doktari, or simply Doctor Murli. This diminutive and unassuming New Delhi import has quietly led a Midwest winegrower revolution over the last 20 years, which has transformed the landscape between the Appalachians and the Rockies

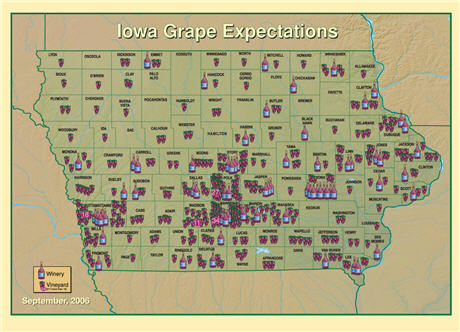

An Iowa State University map of wineries in the state shows the surprising proliferation of the Iowa wine business.

How does he do it? Simple. When a small farm wants to look at winegrowing, Murli is there, gratis, courtesy of the State program. Job One is to look at the terroir and figure out which varieties are most likely to survive the winters and the marketplace in a particular site. Charming and unintimidating, Murli puts his clients through a crash course in basic viticulture and, later on, basic winemaking. There is equipment to pick out, recipes to create, and lab skills to learn.

Because of his belief in basic fundamentals, the wines of Murli’s clients bear his stamp of simple purity: clean, varietal and always well balanced, wines that succeed by not trying too hard. And they have been taking the fairs by storm, first in Ohio, then Nebraska, then Missouri, and now in the Hawkeye State.

These wines are not an acquired taste. Designed to lure first-time tourists away from Budweiser and Pepsi, they are long on varietal fruit and zesty acidity, with every sugar level from bone dry to sticky sweet. Another great spin-off of the short growing season is that, for all their rich flavor, Iowa alcohols clock in at a civilized 10 – 12 percent. Prices are easy on the wallet. For adventuresome wine lovers tired of the under-fruited, over-stylized trends now plaguing more established regions, Iowa may just be tonight’s perfect choice.

Upper Meets Lower Midwest: The Two Varietal Strategies of Iowa

Besides needing a short growing season and the ability to ward off mildew in its humid summers, varietal choices in Iowa have less to do with climate in the growing season than with winterkills survival [pdf] , which requires a wood hardening that most vinifera can’t manage. Iowa’s viticulture is thus divided into two subregions: 1) cold, and 2) friggin’ bone chilling. The Arctic winds of January blow down off the Canadian Shield through Minnesota, plunging Northern Iowa to -30°F in a bad year.Two grapes capable of withstanding cold-climate Upper Midwest conditions, a new white and a venerable red of long standing, have emerged to lead the pack as Iowa’s signature varietals: the aromatic Minnesota-bred charmer Edelweiss and the venerable French/American hybrid Marechal Foch, whose unique attributes have created a devoted cult following. Other cold-hardy whites include La Crescent, La Crosse, Brianna, Petite Amie, and St. Pepin, and the red list is topped by St. Croix, De Chaunac, and Frontenac. [Check out APPELLATION AMERICA’s detailed Grape Index for information on these and other mentioned varietals.]

By the time the winter gales reach the southern part of the State, they have warmed to a nice balmy -10°F, warm enough for the traditional hybrids now popular in New York and Missouri – familiar dry whites such as Seyval Blanc and Vidal Blanc, the recent sensation Chardonel, the delicious Riesling-like Vignoles, the perfumey Traminette, and the popular fruit-bomb rosé Catawba. Reds include the rustic, high acid Baco Noir, the perfumey, Burgundy-like Chambourcin, and the big Rhône-style native American grape Norton.

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

click here

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

click here

Print this article | Email this article | More about Iowa | More from Clark Smith