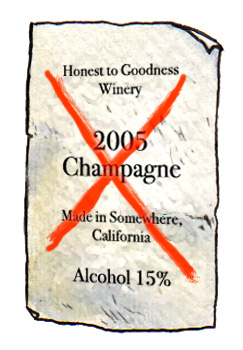

Alcohol percentages noted on lablels seem to be dropping after rising for many years.

Goldfarb’s Pressing Matters

Are Hot Wines Getting “Warm”?

Alcohol levels in U.S. wines have increased in the past decade. Look on the shelf of any wine store to see the evidence, as alcohol percentages noted on labels commonly stay above 14 percent. But those numbers seem to be coming down now. Well, maybe.

by

Alan Goldfarb

December 21, 2006

There’s been lots of chatter about “hangtime” or prolonged maturation of grapes, a topic promulgated by certain growers and thereby fostered by a small cadre of wine writers – yours truly among them. Thus, if my very informal survey is any indication, we may be witnessing the beginning of a trend that will see alcohol levels drop over the next few vintages.

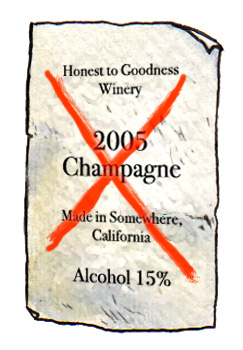

It used to be, of course, that the gold standard – read French – was usually set at about 12.5 percent alcohol. In a good year, this would be an integral component that would produce what was thought to be a balanced wine. But with new world sensibilities of flavor and fiercely fought commerce--and given the inherent warmer climates of California, Australia and South America--alcohol levels have crept to 15 and even 16 percent – unheard of before in a non-dessert wine.

It used to be, of course, that the gold standard – read French – was usually set at about 12.5 percent alcohol. In a good year, this would be an integral component that would produce what was thought to be a balanced wine. But with new world sensibilities of flavor and fiercely fought commerce--and given the inherent warmer climates of California, Australia and South America--alcohol levels have crept to 15 and even 16 percent – unheard of before in a non-dessert wine.

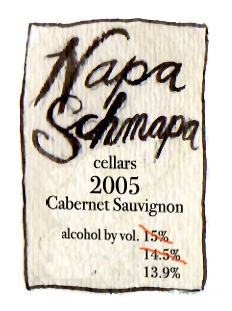

Given that 14 percent is the U.S. Tax and Trade Bureau’s (TTB) tariff-related demarcation point between “table wine” and “dessert wine”; and that 14 percent is a kind of Maginot line or a tacit point at which some wine critics begin to blanch, anything under 14 percent in wines from the Napa Valley becomes a magnet for further inspection.

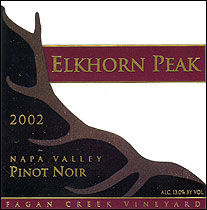

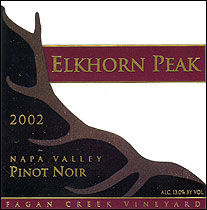

For instance, wines such as Elkhorn Peak’s 2002 Pinot Noir, which came in at a listed 13 percent (the lowest percentage incidentally, in the survey), and the ’03 Amici Cabernet Sauvignon and the ’03 Corison Kronos Cabernet (both at 13.4), all exhibited perfect pitch – or balance. That is, in addition to the restrained alcohol levels not contributing to the sweetness or hotness of the wine, the fruit was bright but not overly ripe, and the acids – TA (total acidity – a measure of all the acids) and the pH (a measurement of the acidity in grape juice) – served contrapuntally. (See Alan Goldfarb’s reviews of these wines at Elkhorn Peak Cellars, Amici, Corison Winery.)

(Note: While conducting the survey I kept in mind that some winemakers may or may not have manipulated their wines in the cellar to achieve better balance; or fudged the numbers for the taxman. As for alcohol levels, they can be reduced by the use of technical devices such as by reverse osmosis or through a spinning cone, or by adding water. All methods, which are commonly known to be used, are legal but have restrictions. As for the tax implications, the Feds require an approximately 50 percent higher tax on alcohol levels above 14.001 percent. That can total as much as $3.73 per case, but is discounted for smaller wineries. Additionally, winemakers are legally afforded a leeway on labels of 1 to 1.5 percent either way.)

So, are alcohol levels trending down? Given that my survey is nothing more than a straw poll and certainly not based upon scientific data, I asked several industry sources if they are witnessing what I am.

“Yes I do think it’s a trend. … From our standpoint -- Pinot Noir production -- we’re looking to get back to lower alcohol-content wines,” says Ken Nerlove, the owner of Elkhorn Peak Winery in Jamieson Canyon. “You need to have the alcohol in the wine, but when you start to get to higher levels, you start to get that hot taste and that’s not considered a taste you want.

“We’ve tended to pick the grapes at a lower sugar level to keep alcohol down. This year we picked our grapes at 24.5 Brix which gives you 12.25 percent alcohol. (Which, by the time the wine is finished, should come in just under 14). “Our winemaker (Kent Rasmussen) feels you get a better balanced wine (with lower alcohol levels) and we feel the public is getting away from high alcohol wine.”

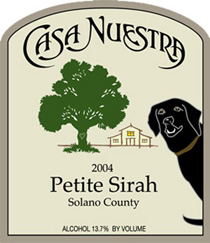

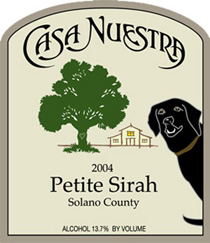

However, Allen Price, the winemaker at Casa Nuestra northeast of St. Helena, doesn’t think we’re seeing a trend of lower alcohol wines, although it is his practice to try and keep his wines under 14 percent.

However, Allen Price, the winemaker at Casa Nuestra northeast of St. Helena, doesn’t think we’re seeing a trend of lower alcohol wines, although it is his practice to try and keep his wines under 14 percent.

“No, it’s not a trend. The trend is still strong to go way over 14, which is pursuing the holy grail of wines of special interest,” Price believes. “I don’t think the backlash has hit yet.”

By “special interest,” Price refers to the so-called “cult” wines, wines that are extremely hard to find, extremely expensive, and can be extremely high in alcohol. They are wines that are favored by the few who have disposable income, as well as by collectors. He insists that he doesn’t make wines with high alcohol in the interest of what he calls “relief of people.” By which he means, “That’s about intoxication and palate fatigue (and) that happens above 14 percent.

“These wines of special interest show well, but if you are going to try two sips of them, you’re going to risk a backlash of palate fatigue.

“If you’re under 14 percent, it makes the wine a lot more drinkable. You do sacrifice some of the richness though if you stay in that department. Wines, particularly reds, get richer if you go 14, 15, 16. …But alcohol is part of the flavor. Consequently, we try to keep our wines at about 13.6, 13.7.”

“If you’re under 14 percent, it makes the wine a lot more drinkable. You do sacrifice some of the richness though if you stay in that department. Wines, particularly reds, get richer if you go 14, 15, 16. …But alcohol is part of the flavor. Consequently, we try to keep our wines at about 13.6, 13.7.”

Charles Smith, the co-owner and winemaker at Smith-Madrone Winery on Spring Mountain, is also a believer that alcohol is a necessary component to being “part of the flavor.”

“Some of the over-14 percent wines are very good. That’s undeniable,” Smith concurs. “It’s possible to have a very high-alcohol wine in the 14.5-14.8 range that’s “moderate, relatively speaking.”

The pH and TA levels have to be in balance with the alcohol, says Smith, who has always strived to keep his wines relatively low in alcohol. However, he concedes even his wines are “creeping up” and stepping into that field mined with 14-point wines. “We’re susceptible,” is how he puts it. “We have to compete. I admire some of those wines. I have to confess our wines are going up, too. I would say that literally no one is picking Cab at 23.5 brix any longer. It’s just not happening. “The new 23.5 is 25.”

Thus, Smith thinks, “… There are wines that are very ripe and very high in alcohol and then there’s a group of wines for me that don’t work. The pHs are too high, the TAs are too low, there’s no backbone and they’re made to drink and drink now. … They’ve pushed it over the cliff. I find after the first sip or two they just don’t have enough grip.”

Cathy Corison of Corison Winery, just south of St. Helena, believes that she’s witnessing a “sea change” of less alcoholic wines. She herself is a believer in lower alcohol. Bu

It used to be, of course, that the gold standard – read French – was usually set at about 12.5 percent alcohol. In a good year, this would be an integral component that would produce what was thought to be a balanced wine. But with new world sensibilities of flavor and fiercely fought commerce--and given the inherent warmer climates of California, Australia and South America--alcohol levels have crept to 15 and even 16 percent – unheard of before in a non-dessert wine.

It used to be, of course, that the gold standard – read French – was usually set at about 12.5 percent alcohol. In a good year, this would be an integral component that would produce what was thought to be a balanced wine. But with new world sensibilities of flavor and fiercely fought commerce--and given the inherent warmer climates of California, Australia and South America--alcohol levels have crept to 15 and even 16 percent – unheard of before in a non-dessert wine. Given that 14 percent is the U.S. Tax and Trade Bureau’s (TTB) tariff-related demarcation point between “table wine” and “dessert wine”; and that 14 percent is a kind of Maginot line or a tacit point at which some wine critics begin to blanch, anything under 14 percent in wines from the Napa Valley becomes a magnet for further inspection.

For instance, wines such as Elkhorn Peak’s 2002 Pinot Noir, which came in at a listed 13 percent (the lowest percentage incidentally, in the survey), and the ’03 Amici Cabernet Sauvignon and the ’03 Corison Kronos Cabernet (both at 13.4), all exhibited perfect pitch – or balance. That is, in addition to the restrained alcohol levels not contributing to the sweetness or hotness of the wine, the fruit was bright but not overly ripe, and the acids – TA (total acidity – a measure of all the acids) and the pH (a measurement of the acidity in grape juice) – served contrapuntally. (See Alan Goldfarb’s reviews of these wines at Elkhorn Peak Cellars, Amici, Corison Winery.)

(Note: While conducting the survey I kept in mind that some winemakers may or may not have manipulated their wines in the cellar to achieve better balance; or fudged the numbers for the taxman. As for alcohol levels, they can be reduced by the use of technical devices such as by reverse osmosis or through a spinning cone, or by adding water. All methods, which are commonly known to be used, are legal but have restrictions. As for the tax implications, the Feds require an approximately 50 percent higher tax on alcohol levels above 14.001 percent. That can total as much as $3.73 per case, but is discounted for smaller wineries. Additionally, winemakers are legally afforded a leeway on labels of 1 to 1.5 percent either way.)

So, are alcohol levels trending down? Given that my survey is nothing more than a straw poll and certainly not based upon scientific data, I asked several industry sources if they are witnessing what I am.

“Yes I do think it’s a trend. … From our standpoint -- Pinot Noir production -- we’re looking to get back to lower alcohol-content wines,” says Ken Nerlove, the owner of Elkhorn Peak Winery in Jamieson Canyon. “You need to have the alcohol in the wine, but when you start to get to higher levels, you start to get that hot taste and that’s not considered a taste you want.

“We’ve tended to pick the grapes at a lower sugar level to keep alcohol down. This year we picked our grapes at 24.5 Brix which gives you 12.25 percent alcohol. (Which, by the time the wine is finished, should come in just under 14). “Our winemaker (Kent Rasmussen) feels you get a better balanced wine (with lower alcohol levels) and we feel the public is getting away from high alcohol wine.”

However, Allen Price, the winemaker at Casa Nuestra northeast of St. Helena, doesn’t think we’re seeing a trend of lower alcohol wines, although it is his practice to try and keep his wines under 14 percent.

However, Allen Price, the winemaker at Casa Nuestra northeast of St. Helena, doesn’t think we’re seeing a trend of lower alcohol wines, although it is his practice to try and keep his wines under 14 percent. “No, it’s not a trend. The trend is still strong to go way over 14, which is pursuing the holy grail of wines of special interest,” Price believes. “I don’t think the backlash has hit yet.”

By “special interest,” Price refers to the so-called “cult” wines, wines that are extremely hard to find, extremely expensive, and can be extremely high in alcohol. They are wines that are favored by the few who have disposable income, as well as by collectors. He insists that he doesn’t make wines with high alcohol in the interest of what he calls “relief of people.” By which he means, “That’s about intoxication and palate fatigue (and) that happens above 14 percent.

“These wines of special interest show well, but if you are going to try two sips of them, you’re going to risk a backlash of palate fatigue.

“If you’re under 14 percent, it makes the wine a lot more drinkable. You do sacrifice some of the richness though if you stay in that department. Wines, particularly reds, get richer if you go 14, 15, 16. …But alcohol is part of the flavor. Consequently, we try to keep our wines at about 13.6, 13.7.”

“If you’re under 14 percent, it makes the wine a lot more drinkable. You do sacrifice some of the richness though if you stay in that department. Wines, particularly reds, get richer if you go 14, 15, 16. …But alcohol is part of the flavor. Consequently, we try to keep our wines at about 13.6, 13.7.” Charles Smith, the co-owner and winemaker at Smith-Madrone Winery on Spring Mountain, is also a believer that alcohol is a necessary component to being “part of the flavor.”

“Some of the over-14 percent wines are very good. That’s undeniable,” Smith concurs. “It’s possible to have a very high-alcohol wine in the 14.5-14.8 range that’s “moderate, relatively speaking.”

The pH and TA levels have to be in balance with the alcohol, says Smith, who has always strived to keep his wines relatively low in alcohol. However, he concedes even his wines are “creeping up” and stepping into that field mined with 14-point wines. “We’re susceptible,” is how he puts it. “We have to compete. I admire some of those wines. I have to confess our wines are going up, too. I would say that literally no one is picking Cab at 23.5 brix any longer. It’s just not happening. “The new 23.5 is 25.”

Thus, Smith thinks, “… There are wines that are very ripe and very high in alcohol and then there’s a group of wines for me that don’t work. The pHs are too high, the TAs are too low, there’s no backbone and they’re made to drink and drink now. … They’ve pushed it over the cliff. I find after the first sip or two they just don’t have enough grip.”

Cathy Corison of Corison Winery, just south of St. Helena, believes that she’s witnessing a “sea change” of less alcoholic wines. She herself is a believer in lower alcohol. Bu