“Whatever people in general do not understand, they are always prepared to dislike; the incomprehensible is always the obnoxious.”

~Letitia E. Landon, author (1802-1838)

In this space, it’s my intention to provide wine enthusiasts with a winemaking insider’s point of view on issues which concern them. As much as possible, I intend to skirt my personal endeavors and serve the readers’ interest above my own. But to do so, it seems I need to clear the air, just this once, by delving once again into the tired old issue of wine manipulation.

Here’s the reader feedback from

my first column. Kudos for content, dings for not dodging the controversy which surrounds my persona. Apparently, if I’m to be of any use as a window for readers on the winemaker’s perspective, we need to address the fact that a lot of people are not pleased with me.

For those of you who have been off-planet lately, I live at the center of a global maelstrom concerning winemakers’ obligations to consumers. The charge: Aiding and Abetting Wine Manipulation in the First Degree. Defendant’s Plea: Guilty as Charged. And by the way, where’s my Medal of Honor?

In this discussion, I don’t intend to call anybody out. I’ll mention by name only those who have conducted themselves with honor in this debate and deserve mention for it. To aid discussion of this complex and highly charged subject, I’m going to try some analogies to other branches of cooking and presentation: classic cuisine, musicianship, even women’s cosmetics.

Critics and winemakers have hit a stormy little patch in a great marriage, and we need to talk. We’re driving the kids crazy.

The ire and vitriol which characterize this debate have the taste of betrayal and broken agreements. I’m going to try to get to the bottom of what those are. I’m confident we can put enmity behind us once we realize that all the players are good guys who want the same things. Critics and winemakers have hit a stormy little patch in a great marriage, and we need to talk. We’re driving the kids crazy.

An honest, open debate on this topic would have been well-settled years ago. Ideally, proponents of the new techniques would present their wines and skeptics would taste them and discuss their findings. None of this is happening. Unlike the free, open ‘70’s and ‘80’s, winemakers are lying low and keeping mum while paparazzi fire live ammo over their heads.

Before I launch into a discussion of modern winemaking tools, I should articulate my bias for those who do not know me. Actually I have two. The first is as an owner of Vinovation Inc., a wine production consulting firm which sells goods, services, machines and consulting to 1200 wineries worldwide. Having dedicated myself to improving winemaking, I’m inclined to argue in defense of my approach. As I explained in my last piece on alcohol levels, I bear some responsibility for the shift in attitude connected with the general rise in alcohol levels in this country. As

Tom Wark rightly observed, I have been at the center of the move toward the Big Wine. I certainly don’t apologize for my contribution,

WineSmith’s Napa-grown “Faux Chablis” is a dead ringer for the real thing.

WineSmith’s Napa-grown “Faux Chablis” is a dead ringer for the real thing.

but it’s fair to say that there have been plenty of terrible wines made as we flail around trying to perfect this newly-born sort of New World long suit.

Secondly, I make and sell wine. Since my training is largely French, the niche I’ve chosen is stylistically Old World. I enjoy offering wines which show possibilities for California outside the mainstream:

Chablis-style Chardonnays, racy Cab Francs, and Loire-style Chenin Blanc aged sur lies. That’s pretty confusing to the marketplace, so I’m not likely to grow much. I’d be very pleased if readers of this column decided to

try my experiments and judge my success for themselves.

UK wine writer Jaime Goode went through my wines in November and came up with an article which I thought articulated my struggle well:

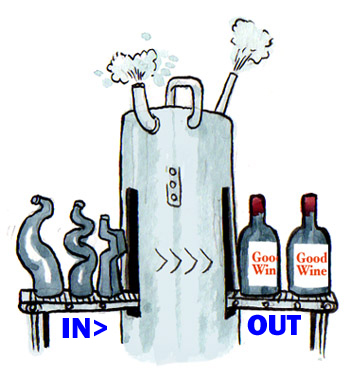

The surprising juxtaposition of Technology and Natural Winemaking.

here

here are plenty of heroes in this story. One is Randy Dunn, who is quite open in his

praise of RO (Reverse Osmosis) and his

condemnation of overripe fruit. Another is Michael Havens, who agreed in 2001, in the interest of openness and consumer education, to have his face plastered all over the

The New York Times as an “outed” micro-ox practitioner. There are some journalist heroes out there, too. Some have supported the politically incorrect view that good wine is good wine, and those who can enhance distinctive terroir expression are welcome to their tools:

Jamie Goode

,

Patrick Matthews

,

Derrick Schneider. Others lean to the conservative, but are tireless, rigorous and open:

Eric Asimov,

Alice Feiring.

You decide: Is the wine industry’s glass half full or half empty?

You decide: Is the wine industry’s glass half full or half empty?There are villains, too. Some writers are widening the information disconnect between winemakers and wine buffs with all the good-hearted integrity of a Beverly Hills divorce attorney. Many

paparazzi who have come to interview me, agenda in hand, tasted through my wines, and responded like any modern journalist when confronted with an inconvenient truth. They ignored it. Despite many compliments delivered in person, their lambastes of wine technology contain scarcely a word about my wines.

I make Eurocentric, balanced, distinctive, somewhat offbeat wines, which share the purpose of presenting alternative styles for California and thus don’t resemble the mainstream. They are not impact wines. They are harmonious, skillfully crafted wines of balance and harmony, each a unique expression of terroir. They age well.

Writers love to coax winemakers to be open. Then sometimes they nail them. When I started posting the particulars of techniques used for specific wines, it proved helpful in convincing Vinovation’s winery clients to explore style options outside the lockstep mainstream, but among the media, it has mostly made me a target. No points for honesty from this bunch. Since I consider inauthenticity the heart of the problem, it’s ironic to watch critics go for the throat when a winemaker tells the truth.

Likewise there are retailers who have joined the bandwagon, dropping wines they really like when they discover they are made by someone willing to be honest about their production methods. More dupes than villains.

I don’t know if that certain writer for the

Wine Spectator who started it all in 2001 (and continues to rail against technology) has ever tasted my wines, though I sent him a flight. He won’t return my calls.

Marketing vs. Terroir: Ninety percent of the wine we drink is supplied by ten percent of wineries, mostly big corporate outfits - commodity McWine in a dozen conventional styles - who deliver their product with scientific precision and industrial efficiency.

Marketing vs. Terroir: Ninety percent of the wine we drink is supplied by ten percent of wineries, mostly big corporate outfits - commodity McWine in a dozen conventional styles - who deliver their product with scientific precision and industrial efficiency.It is time for all players to start being straight. It feels to me like many journalists are afraid to put their weapons on safety and venture out from their entrenched positions. Ye passionate scribes: I implore you to make a rigorous accounting of your politics, and consider if the wine world might be better off if winemakers could speak freely of their work without attracting fragging from those who claim to revere their craft.

It’s the downside of bounty. Unlike in my salad days, a flat-out crappy bottle of wine today is quite rare. The problems which commonly haunted wine lists twenty years ago – oxidized, sour, vinegary, or just incredibly funky – are scarce today. But the science and practical expertise which eradicated these problems have sown their own generation of complaints.

It’s a timeless irony. The problems we complain of today are actually children of the solutions we found to yesterday’s problems. Our

malaise du jour? Much of this good clean wine is pretty doggone boring.

The Good, The Bad and the Funky

No doubt about it. Ninety percent of the wine we drink is supplied by ten percent of wineries, mostly big corporate outfits - commodity McWine in a dozen conventional styles - who deliver their product with scientific precision and industrial efficiency. For the most part, marketing departments at large wineries and the winemakers who work for them are astoundingly responsive to market demands. Most wine is a commodity that sells based on very specific parameters that have been honed over the last couple of decades. The simple fact is that unusual wines, wines of distinction, don’t sell very easily, so the mega-boutiques don’t waste time and money making them. For them, producing “interesting” wine equals fiscal suicide.

The remaining tenth is divided among thousands of small niche producers whose main problem is an honest point of distinction. It may be an extrinsic strategy: a cute dog on

The simple fact is that unusual wines, wines of distinction, don’t sell very easily, so the mega-boutiques don’t waste time and money making them.

the label, a memorable tasting room experience, a promising appellation pedigree, or some other oddity unrelated to what’s in the bottle. But often as not, it’s intrinsic, i.e. in the bottle, a distinctive style which builds a following over time.

Anyone who hasn’t tried to do so can’t possibly imagine how much work it is to establish a new brand today. In truth, there is almost no receptivity for a new player outside the norm. You would think that all that web-kvetching about terroir would show up in the marketplace in a way that a guy could use to build a brand.

In your dreams, maybe. It’s really weird to spend all day trying to shoehorn a damned good Euro-centric Cabernet Franc or Chablis-styled Chardonnay onto crowded retail shelves and then to come home to an Internet forever moaning about sameness and “anywhere-ness.” Us small winery guys keep wondering: When are you te

here are plenty of heroes in this story. One is Randy Dunn, who is quite open in his praise of RO (Reverse Osmosis) and his condemnation of overripe fruit. Another is Michael Havens, who agreed in 2001, in the interest of openness and consumer education, to have his face plastered all over the The New York Times as an “outed” micro-ox practitioner. There are some journalist heroes out there, too. Some have supported the politically incorrect view that good wine is good wine, and those who can enhance distinctive terroir expression are welcome to their tools: Jamie Goode

here are plenty of heroes in this story. One is Randy Dunn, who is quite open in his praise of RO (Reverse Osmosis) and his condemnation of overripe fruit. Another is Michael Havens, who agreed in 2001, in the interest of openness and consumer education, to have his face plastered all over the The New York Times as an “outed” micro-ox practitioner. There are some journalist heroes out there, too. Some have supported the politically incorrect view that good wine is good wine, and those who can enhance distinctive terroir expression are welcome to their tools: Jamie Goode

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,