The characteristics of the wine in your glass depend in part on the terroir in which the

grapes were grown.

Why Terroir is Essential To Wine Evaluation

The wine rating numbers game has blinded reviewers and consumers who don’t consider the unique influences of taste which are contributed by where the grapes were grown. It is time to take terroir into consideration.

by

Dan Berger

December 27, 2006

Since most people who call themselves wine collectors buy wines which achieve high scores in a revered wine publication, the question of difference among wines is a key factor in how they decide what to buy. You may have seen the cartoon (drawn by artist Bob Johnson) in which the guy at the tasting bar says, “This wine is repulsive,” and the clerk tells him that the wine just got a 98 from a wine magazine. The guy replies, “I’ll take a case.”

So the fact that these people may not like a wine on first taste doesn’t necessarily mean that they begin to ignore the reviewer. It may mean that they begin to learn to like the style of wine he likes. And if the reviewers are ignoring certain valid styles of wine and rewarding only the narrow bandwidth of style they prefer, otherwise excellent wines are being ignored.

A problem here is that few people taste before they buy and those who do often have so little schooling in the breadth of wines available that they wouldn’t appreciate a “classic” wine from a region about which they know little.

Cases in point are everywhere. The first time wine lovers try a Chinon, a Brunello, or a Cahors, they might have raised eyebrows and asked rhetorically, “What’s this stuff?” No, they’re not easily understood, but all have their adherents.

Few people I know purchase a range of single bottles of just-released wine, taste them all with similar wines about which little is known, and then try to make a decision about which wine will justify an outlay of cash. This takes a lot of work, and the short-hand method is to simply to buy by the numbers.

Few people I know purchase a range of single bottles of just-released wine, taste them all with similar wines about which little is known, and then try to make a decision about which wine will justify an outlay of cash. This takes a lot of work, and the short-hand method is to simply to buy by the numbers.

But tasting the wine before buying is no guarantee of a good consumer decision, especially if the tasters all go by weight. To many people, the key factor in what wines to buy is power. For me, weight is one of the least important aspects of a fine wine, and one that ought to be considered only after other elements are present in the wine. Balance is critical for all wines, both those we’ll consume now and those intended to be aged.

But another crucial factor that adds value to a wine for us is regionality -- the ability of a wine to show graphically where it came from and what it says about its site. It is this very factor that appears to be completely missing in the glossy magazines and private newsletters that review wine based almost solely on weight.

I once was asked if I could tell from a smell and a taste where a particular wine came from. I said it was difficult, especially these days when wines are being made so similarly in terms of over-ripe components. Today, it’s hard to tell the difference between some Pinot Noir and Syrah.

To be sure, varietal character is certainly a more vital aspect of a wine’s personality, so I give added value to a wine that offers a distinctive regional character, especially if that character is one that is fairly identifiable, and typical of the area. Accordingly, if the major reviewers are giving high scores to Cabernet Sauvignons that smell like Syrah, it’s evident why they may be willing to completely ignore the even more subtle elements of regional character.

This is a topic that is hard to discuss since the elements which comprise terroir can be subtle. It certainly means less in the United States than it does in Europe or even Australia. The Aussies in particular demand and appreciate the regional characteristics in their own wines. They see the substantive differences between Shiraz from Coonawarra, Hunter and Barossa. They find, and truly understand, the different characteristics of Riesling from Clare, Eden, Coonawarra and Barossa. In some ways, it speaks to their sophistication; the fact that they can dissect wines and appreciate them on different levels.

They find, and truly understand, the different characteristics of Riesling from Clare, Eden, Coonawarra and Barossa. In some ways, it speaks to their sophistication; the fact that they can dissect wines and appreciate them on different levels.

Similarly, Bordeaux used to be a place of regional mandate in a wine. A St.-Estephe was harder than a Margaux, and you just accepted that fact, and reveled in the mystery and the difference. As scores became more and more the dominant means of “describing” a wine, the need to see terroir issues as essential in the appreciation of a wine declined. Now some Volnay producers aim to make a wine that has the weight of Echezeaux.

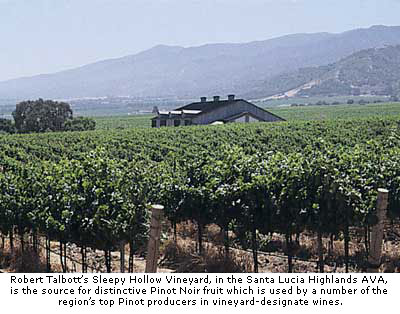

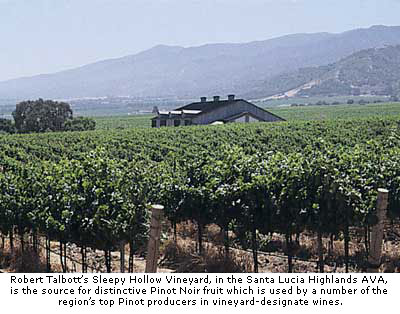

In California, the distinction between a Russian River Valley Pinot Noir and one from Santa Lucia Highlands has been one of the least looked-at issues, especially when one wine gets a 92 and the other an 87, making the former wine “better” than the latter. Yet if one were to pour the two wines blind for various groups of qualified wine judges under differing criteria, look at how the results could be skewed.

Indeed, I see regionality as a vital aspect of the evaluation of any wine. Good judges should use regionality to justify a rating for each wine. But regionality is not automatically a part of most American wine judges’ psyche. Weight, richness, and “hedonistic” appreciation of a wine’s flavors seem far more the dominant aspects of most evaluations we see or read about.

Indeed, I see regionality as a vital aspect of the evaluation of any wine. Good judges should use regionality to justify a rating for each wine. But regionality is not automatically a part of most American wine judges’ psyche. Weight, richness, and “hedonistic” appreciation of a wine’s flavors seem far more the dominant aspects of most evaluations we see or read about.

True, we have a fallacy here. If judges are judging wines in a truly double-blind setting, then they cannot know the region from which each wine comes, and thus for them to rate a wine highly as typical of a particular region is risky. What if the wine doesn’t actually come from the region the judge assumes it did?

Yet the Australians have a perfect justification for awarding a gold medal to a Shiraz that seems like it’s

So the fact that these people may not like a wine on first taste doesn’t necessarily mean that they begin to ignore the reviewer. It may mean that they begin to learn to like the style of wine he likes. And if the reviewers are ignoring certain valid styles of wine and rewarding only the narrow bandwidth of style they prefer, otherwise excellent wines are being ignored.

A problem here is that few people taste before they buy and those who do often have so little schooling in the breadth of wines available that they wouldn’t appreciate a “classic” wine from a region about which they know little.

Cases in point are everywhere. The first time wine lovers try a Chinon, a Brunello, or a Cahors, they might have raised eyebrows and asked rhetorically, “What’s this stuff?” No, they’re not easily understood, but all have their adherents.

Few people I know purchase a range of single bottles of just-released wine, taste them all with similar wines about which little is known, and then try to make a decision about which wine will justify an outlay of cash. This takes a lot of work, and the short-hand method is to simply to buy by the numbers.

Few people I know purchase a range of single bottles of just-released wine, taste them all with similar wines about which little is known, and then try to make a decision about which wine will justify an outlay of cash. This takes a lot of work, and the short-hand method is to simply to buy by the numbers.

But tasting the wine before buying is no guarantee of a good consumer decision, especially if the tasters all go by weight. To many people, the key factor in what wines to buy is power. For me, weight is one of the least important aspects of a fine wine, and one that ought to be considered only after other elements are present in the wine. Balance is critical for all wines, both those we’ll consume now and those intended to be aged.

But another crucial factor that adds value to a wine for us is regionality -- the ability of a wine to show graphically where it came from and what it says about its site. It is this very factor that appears to be completely missing in the glossy magazines and private newsletters that review wine based almost solely on weight.

I once was asked if I could tell from a smell and a taste where a particular wine came from. I said it was difficult, especially these days when wines are being made so similarly in terms of over-ripe components. Today, it’s hard to tell the difference between some Pinot Noir and Syrah.

To be sure, varietal character is certainly a more vital aspect of a wine’s personality, so I give added value to a wine that offers a distinctive regional character, especially if that character is one that is fairly identifiable, and typical of the area. Accordingly, if the major reviewers are giving high scores to Cabernet Sauvignons that smell like Syrah, it’s evident why they may be willing to completely ignore the even more subtle elements of regional character.

This is a topic that is hard to discuss since the elements which comprise terroir can be subtle. It certainly means less in the United States than it does in Europe or even Australia. The Aussies in particular demand and appreciate the regional characteristics in their own wines. They see the substantive differences between Shiraz from Coonawarra, Hunter and Barossa.

They find, and truly understand, the different characteristics of Riesling from Clare, Eden, Coonawarra and Barossa. In some ways, it speaks to their sophistication; the fact that they can dissect wines and appreciate them on different levels.

They find, and truly understand, the different characteristics of Riesling from Clare, Eden, Coonawarra and Barossa. In some ways, it speaks to their sophistication; the fact that they can dissect wines and appreciate them on different levels.

Similarly, Bordeaux used to be a place of regional mandate in a wine. A St.-Estephe was harder than a Margaux, and you just accepted that fact, and reveled in the mystery and the difference. As scores became more and more the dominant means of “describing” a wine, the need to see terroir issues as essential in the appreciation of a wine declined. Now some Volnay producers aim to make a wine that has the weight of Echezeaux.

In California, the distinction between a Russian River Valley Pinot Noir and one from Santa Lucia Highlands has been one of the least looked-at issues, especially when one wine gets a 92 and the other an 87, making the former wine “better” than the latter. Yet if one were to pour the two wines blind for various groups of qualified wine judges under differing criteria, look at how the results could be skewed.

- Group One is told only that the two wines scored 92 and 87. In evaluating the wines, the wine with the greatest intensity would be identified as the 92, for that is (generally) how scores are achieved.

- Group Two is told that the two wines represent different growing regions, and are not told which growing regions they are. In that case, the wine with the stronger pyrazine character (bell pepperish) scores lower, and thus the one with less of that component would be rated higher. Pyrazine taken out of context is not, in and of itself, a particularly inviting characteristic to most wine judges.

- Group Three is served both wines and the tasters are told that one is from Russian River, the other from Santa Lucia Highlands, and that their evaluation ought to include the issue of varietal and regional character, which in each case is slightly different.

Indeed, I see regionality as a vital aspect of the evaluation of any wine. Good judges should use regionality to justify a rating for each wine. But regionality is not automatically a part of most American wine judges’ psyche. Weight, richness, and “hedonistic” appreciation of a wine’s flavors seem far more the dominant aspects of most evaluations we see or read about.

Indeed, I see regionality as a vital aspect of the evaluation of any wine. Good judges should use regionality to justify a rating for each wine. But regionality is not automatically a part of most American wine judges’ psyche. Weight, richness, and “hedonistic” appreciation of a wine’s flavors seem far more the dominant aspects of most evaluations we see or read about.

True, we have a fallacy here. If judges are judging wines in a truly double-blind setting, then they cannot know the region from which each wine comes, and thus for them to rate a wine highly as typical of a particular region is risky. What if the wine doesn’t actually come from the region the judge assumes it did?

Yet the Australians have a perfect justification for awarding a gold medal to a Shiraz that seems like it’s