Because of the severe winters, vines are buried after harvest and dug back up in late Spring in Prince Edward County.

Prince Edward County is Officially

Sanctioned as the Latest DVA

by

Tony Aspler

June 21, 2007

”We are coming of age,” said Richard Johnston, Chair of the Prince Edward County Winegrowers Association (PECWA), as Prince Edward County has become the newest DVA in Ontario, Canada.

“In eight short but challenging years, we have gone from being dismissed as preposterous dreamers trying to grow fine wines in an impossibly cool climate to heralded winegrowers using innovative viticultural techniques to grow prize-winning wines that reflect the unique terroir attributes of this historic agricultural area.”

heralded winegrowers using innovative viticultural techniques to grow prize-winning wines that reflect the unique terroir attributes of this historic agricultural area.”

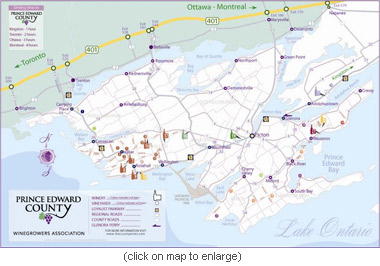

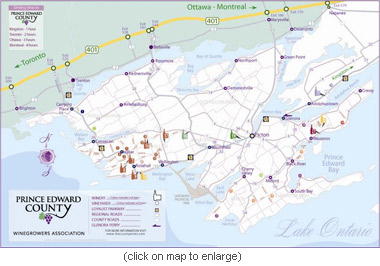

Currently there are 14 wineries operating in the new DVA (Designated Viticultural Area), which juts out into Lake Ontario, a two and a half-hour drive east of Toronto.

Think of Prince Edward County as Sonoma to Niagara’s Napa, slightly less-developed and sophisticated but more rural and bucolic than its established neighbor to the west. The region was settled by United Empire Loyalists fleeing the American Revolution who cleared the land and planted barley and hops. A testament to the wealth of those industrious nineteenth-century farmers who supplied American breweries with their hops and malted barley are the fieldstone farm houses and solid brick homes of Picton, Wellington, and Bloomfield.

With the introduction of tariffs against these products in 1880, the local farmers turned to green peas and other vegetables suitable for canning. A thriving cheese industry developed because the region could sustain animal feed crops as well as fruit orchards. Yes, even grapes were grown. As early as the 1870s, there was a winery in Hillier whose wines were good enough to take a gold medal at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.

At the press conference announcing the Prince Edward County DVA, a poster label tells the story.dredging of the 8-kilometre Murray Canal between 1882 and 1889 effectively cut off the county from the mainland, creating an island of 250,000 acres with an estimated 800 kilometers of shoreline. The land here is essentially a large limestone plateau, rising at its highest point to 150 meters above sea level. The presence of upper-bedrock limestone soil has attracted wine growers who seek to produce the wine lover’s Holy Grail – Pinot Noir. The limestone, threaded with shale and clay, makes for good drainage.

Much of the county has a shallow soil depth before you reach bedrock, but its relatively low rainfall, coupled with the ameliorating effects of the Bay of Quinte and Lake Ontario, makes the region ideal for growing orchard fruits, tomatoes, corn, peas – and wine grapes.

Still, it’s what’s above the ground that will intrigue the wine traveler. This is a landscape of undulating pasture land and charming villages with stone farm houses, pioneer barns, and handsome Victorian mansions. The shoreline culminates in one of the greatest natural beach areas in Canada, Sandbanks Provincial Park. The major cluster of wineries is in Hillier Township, where the gravelly, reddish-brown, clay-loam soil is high in limestone fragments and well drained as a result.

The climate here, and in Athol, North Marysburg, and Hallowel, is moderated by the large bodies of water that surround the county, but the temperature is, on average, lower than that of the Niagara Peninsula. The last spring frost can be as late as mid-May, and the first frost arrives in mid-October, giving Prince Edward a slightly shorter growing season than Ontario’s other viticultural regions.

average, lower than that of the Niagara Peninsula. The last spring frost can be as late as mid-May, and the first frost arrives in mid-October, giving Prince Edward a slightly shorter growing season than Ontario’s other viticultural regions.

Winter is the enemy here, and, to protect the vines against polar temperatures, the growers have to bury their vines. They use a trellis system that allows them to lower the bottom wire so they can “hill” up by back-hoeing to cover next year’s canes with earth. In the spring they uncover them, a laborious and difficult procedure, but this method allows them to save at least 50 per cent of their buds. Given the difficulty of raising wine grapes in this climate, the growers share a kind of messianic quality, a pride and a loyalty to their unrelenting soil similar to what you find among Quebec’s vignerons.

“The VQA was proactively helpful in guiding us through the application process and Minister Phillips has been incredibly quick in agreeing to afford us this new status for which all our members are very grateful,” said Richard Johnston.

Prior to receiving DVA status, county wineries could purchase only a limited amount of grapes grown in other areas. Now, having proven the county’s authenticity as a grape-growing region, wineries will be able to import unlimited tonnage from other Ontario DVAs.

“Admittedly, some members of the industry are nervous that gaining entrance into the wine club could ironically water down the amount of authentic county wines we produce,” said Johnston. “However, our customers show a great preference for wines that are true to this agricultural region and we believe that will continue to be the driving force behind our industry.”

According to their press release, “Under the DVA rules, authentic county wines that receive VQA approval will now be allowed to be designated VQA Prince Edward County on the bottle label; previously they could only be identified as VQA Ontario. However, non-VQA wines will lose the right to bear the county name, which until now has been regulated by PECWA (in order) to give consumers a guarantee that the origin of the wine grapes is 100 per cent county grown.

According to their press release, “Under the DVA rules, authentic county wines that receive VQA approval will now be allowed to be designated VQA Prince Edward County on the bottle label; previously they could only be identified as VQA Ontario. However, non-VQA wines will lose the right to bear the county name, which until now has been regulated by PECWA (in order) to give consumers a guarantee that the origin of the wine grapes is 100 per cent county grown.

Authentic county wines that are not VQA approved will still be allowed to carry the names of the county’s historic townships to identify their place of origin, part of the sub-appellation system developed by PECWA to assure wine authenticity. Wines may not be VQA approved for various reasons, such as a winery has chosen not to seek approval or is not a member of VQA, a wine has failed the VQA tasting test, or the wine is made from grape varietals that are excluded by VQA.

Ironically, under the new DVA rules, VQA wine bearing the county name won’t have to be as auth

“In eight short but challenging years, we have gone from being dismissed as preposterous dreamers trying to grow fine wines in an impossibly cool climate to

heralded winegrowers using innovative viticultural techniques to grow prize-winning wines that reflect the unique terroir attributes of this historic agricultural area.”

heralded winegrowers using innovative viticultural techniques to grow prize-winning wines that reflect the unique terroir attributes of this historic agricultural area.”

Currently there are 14 wineries operating in the new DVA (Designated Viticultural Area), which juts out into Lake Ontario, a two and a half-hour drive east of Toronto.

Think of Prince Edward County as Sonoma to Niagara’s Napa, slightly less-developed and sophisticated but more rural and bucolic than its established neighbor to the west. The region was settled by United Empire Loyalists fleeing the American Revolution who cleared the land and planted barley and hops. A testament to the wealth of those industrious nineteenth-century farmers who supplied American breweries with their hops and malted barley are the fieldstone farm houses and solid brick homes of Picton, Wellington, and Bloomfield.

With the introduction of tariffs against these products in 1880, the local farmers turned to green peas and other vegetables suitable for canning. A thriving cheese industry developed because the region could sustain animal feed crops as well as fruit orchards. Yes, even grapes were grown. As early as the 1870s, there was a winery in Hillier whose wines were good enough to take a gold medal at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.

An Unlikely Wine Region Matures

Like Pelee Island, Prince Edward County might seem an unlikely wine region – an island, formerly a peninsula, midway between Toronto and Kingston. The

At the press conference announcing the Prince Edward County DVA, a poster label tells the story.

Much of the county has a shallow soil depth before you reach bedrock, but its relatively low rainfall, coupled with the ameliorating effects of the Bay of Quinte and Lake Ontario, makes the region ideal for growing orchard fruits, tomatoes, corn, peas – and wine grapes.

Still, it’s what’s above the ground that will intrigue the wine traveler. This is a landscape of undulating pasture land and charming villages with stone farm houses, pioneer barns, and handsome Victorian mansions. The shoreline culminates in one of the greatest natural beach areas in Canada, Sandbanks Provincial Park. The major cluster of wineries is in Hillier Township, where the gravelly, reddish-brown, clay-loam soil is high in limestone fragments and well drained as a result.

The climate here, and in Athol, North Marysburg, and Hallowel, is moderated by the large bodies of water that surround the county, but the temperature is, on

average, lower than that of the Niagara Peninsula. The last spring frost can be as late as mid-May, and the first frost arrives in mid-October, giving Prince Edward a slightly shorter growing season than Ontario’s other viticultural regions.

average, lower than that of the Niagara Peninsula. The last spring frost can be as late as mid-May, and the first frost arrives in mid-October, giving Prince Edward a slightly shorter growing season than Ontario’s other viticultural regions.

Winter is the enemy here, and, to protect the vines against polar temperatures, the growers have to bury their vines. They use a trellis system that allows them to lower the bottom wire so they can “hill” up by back-hoeing to cover next year’s canes with earth. In the spring they uncover them, a laborious and difficult procedure, but this method allows them to save at least 50 per cent of their buds. Given the difficulty of raising wine grapes in this climate, the growers share a kind of messianic quality, a pride and a loyalty to their unrelenting soil similar to what you find among Quebec’s vignerons.

The Long and Windy Road to DVA Approval

Several years ago, PECWA first applied for official recognition to the Vintners Quality Alliance (VQA), which recommends DVA approvals to the Minister of Government Services. They were turned down because the region did not meet the minimum harvest tonnage standards. However, the 2006 harvest of 425 tons far exceeded the minimum 250 tons required and the application was resubmitted.“The VQA was proactively helpful in guiding us through the application process and Minister Phillips has been incredibly quick in agreeing to afford us this new status for which all our members are very grateful,” said Richard Johnston.

Prior to receiving DVA status, county wineries could purchase only a limited amount of grapes grown in other areas. Now, having proven the county’s authenticity as a grape-growing region, wineries will be able to import unlimited tonnage from other Ontario DVAs.

“Admittedly, some members of the industry are nervous that gaining entrance into the wine club could ironically water down the amount of authentic county wines we produce,” said Johnston. “However, our customers show a great preference for wines that are true to this agricultural region and we believe that will continue to be the driving force behind our industry.”

According to their press release, “Under the DVA rules, authentic county wines that receive VQA approval will now be allowed to be designated VQA Prince Edward County on the bottle label; previously they could only be identified as VQA Ontario. However, non-VQA wines will lose the right to bear the county name, which until now has been regulated by PECWA (in order) to give consumers a guarantee that the origin of the wine grapes is 100 per cent county grown.

According to their press release, “Under the DVA rules, authentic county wines that receive VQA approval will now be allowed to be designated VQA Prince Edward County on the bottle label; previously they could only be identified as VQA Ontario. However, non-VQA wines will lose the right to bear the county name, which until now has been regulated by PECWA (in order) to give consumers a guarantee that the origin of the wine grapes is 100 per cent county grown.

Authentic county wines that are not VQA approved will still be allowed to carry the names of the county’s historic townships to identify their place of origin, part of the sub-appellation system developed by PECWA to assure wine authenticity. Wines may not be VQA approved for various reasons, such as a winery has chosen not to seek approval or is not a member of VQA, a wine has failed the VQA tasting test, or the wine is made from grape varietals that are excluded by VQA.

Ironically, under the new DVA rules, VQA wine bearing the county name won’t have to be as auth

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,