Situated beneath Mt. Veeder and the northern boundary of the Carneros, Hendry vineyards exploits its varied terroir.

George Hendry has a head for blocks.

In fact, he has blocks and blocks of (balanced) Zinfandel.

by

Alan Goldfarb

February 22, 2008

eorge Hendry, who has been farming his family’s west Napa Valley vineyard for 33 years and has been making wine from it for Hendry Winery since 1995, is as calculating, meticulous, and focused a vintner as you’ll come across.

eorge Hendry, who has been farming his family’s west Napa Valley vineyard for 33 years and has been making wine from it for Hendry Winery since 1995, is as calculating, meticulous, and focused a vintner as you’ll come across.

From his 117-acre ranch below the southern tip of Mount Veeder, Hendry makes Zinfandel and Cabernet Sauvignon that he describes as “concentrated”. Why concentrated? “Because I like drinking concentrated wines, that’s why,” Hendry answers with a slight edge. “In matters of taste, there’s no dispute.”

But Hendry’s definition of a concentrated wine doesn’t necessarily mean that his wines are over-the-top with fruit or out of balance with gripping alcohol. Generally, the wines, across the board, are in balance and delicious. But make no mistake, Hendry’s wines, especially his Zins, are high in alcohol, usually about 15 percent or better. The alcohol, as amazingly as high as it might be, is hardly discernible from the gestalt of the wine.

It’s All About Concentration

How does he do it? Hendry responds by using that term - concentration - once again.

George Hendry tames his high alcohol Zins with a delicate balancing act.

“You can go to high alcohol before it starts manifesting a peppery character. That’s when you’ve gone beyond the balance.”

Others might be heeding Hendry’s take on the subject, or perhaps it’s because people have finally begun to pay attention to those critics who are hammering the notion of high alcohol wines into the ground seemingly day after day.

At the recently concluded ZAP (Zinfandel Advocates & Producers) annual Zin Drench at Fort Mason in San Francisco, an informal survey by this reporter of about 140 wines revealed some startling statistics. Of the approximately 140 presented at the event exclusively for the press, 54 Zinfandels stated on their labels that they contained alcohol levels of 14 to 14.5 percent. Another 11 listed their alcohol content as less than 14 percent. That’s an astonishing 46 percent of wines that have relatively low levels of alcohol in a varietal category that consistently registers alcohol percentages to the 15 to 16 plus mark. (For the record, five of those 140 wines indeed had stated alcohol numbers of 16 to 16.9 percent - yikes!)

George Hendry, whose Zins were represented that day, is well aware of the alcohol debate. “You’d better believe I am (aware of alcohol), (and) I’m not an admirer of high alcohol wines. When I start getting a peppery character (in my wines) it means I can’t taste the other things in the wine. The pepper does all the talking.”

He contends that it’s the alcohol that feels hot in a wine, and not necessarily the black pepper flavors that critics and consumers use to describe a typical Zinfandel. So, I ask him point blank: Will we ever see Zinfandel consistently at 14.5 alcohol? He answers in his succinct manner: “Tell me what the market wants and I will figure out how to do it.”

You can make a 14.5 Zin?

“Of course,” comes his immediate response. “You can pick less ripe, which is going to make the wine hard to drink early on. We get it ripe and we decide. If we wanted to make a lighter-style wine, then we’d go ahead and pick about what we do now, get a higher crop, saignée (bleed off a portion of red wine after coming in contact with the skins). And make a claret style.”

In addition to what the market thinks it desires, there is an additional question that, to lay ears, has never gotten a

satisfactory answer - until now. That is, why does Zinfandel, more than any other variety, seem to be steeped in all that alcohol?

satisfactory answer - until now. That is, why does Zinfandel, more than any other variety, seem to be steeped in all that alcohol?

“Zinfandel sequesters sugar in the skins,” Hendry explains. “When you’re making the wine, during the first several days in the fermenter, sugar levels increase dramatically, going up 5 percent. That doesn’t happen in Cabernet or Pinot Noir. Often what happens is people underestimate their sugar. And pretty soon you have a high-alcohol wine and the yeast has died before they’re finished.”

Will producers then, make lower-alcohol Zinfandels?

“It certainly can be done, but there’s not a good market for that right now,” Hendry says, stating the obvious. Where apparently there is a market, in addition to higher alcohol wines, is from consumers who are beginning to understand the concept of terroir and the various regions and sites from where grapes originate.

Tending Vines Block by Block

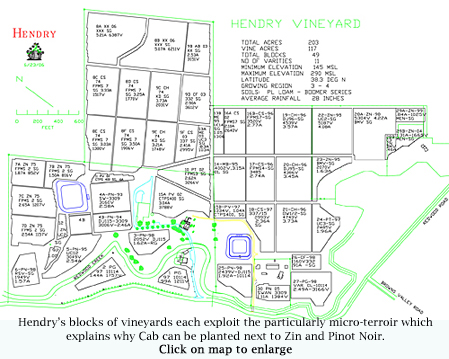

Hendry knows this all too well. He’s devoted his winegrowing life to the notion that site – or in his case, a vineyard block – is what captures the imagination of the North American wine drinker.“The block is the basic management unit for farming grapes,” is his mantra, and marketing tool. “We communicate this on our label to our customers.”

Indeed, the ranch has 49 blocks consisting of Albariño, Pinot Gris, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, and Cabernet Sauvignon, and of course, Zinfandel. Each of those blocks Hendry says, “Is a product of our efforts to discover the vineyard’s full potential. Soil type, exposure, clones and rootstocks are all variables that determine block boundaries. By dividing the vineyard as we do, we are able to study the interactions of these factors, and learn how they influence fruit composition and wine quality. …We devote much of our time to understanding its variations on small scales.”

Indeed, the ranch has 49 blocks consisting of Albariño, Pinot Gris, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, and Cabernet Sauvignon, and of course, Zinfandel. Each of those blocks Hendry says, “Is a product of our efforts to discover the vineyard’s full potential. Soil type, exposure, clones and rootstocks are all variables that determine block boundaries. By dividing the vineyard as we do, we are able to study the interactions of these factors, and learn how they influence fruit composition and wine quality. …We devote much of our time to understanding its variations on small scales.”

But it is the genetic material - the clonal selections - that Hendry and his nephew Mike, who is the vineyard manager, believe determines the essence of how a wine manifests on the palate. “Within some of those blocks, what distinguishes them is not soil differences, but clonal differences,” believes Mike Hendry. “It’s not always soil-based.

His uncle chimes in, “I second that. Clonal differences tend to trump small differences in soil.

So, are you debunking terroir?

“By no means,” explains George Hendry. “We have a Chardonnay vineyard (Block 27) which was a low block with lots of moisture (down by a creek). It was producing a light, less concentrated wine. We put Pinot Gris down there. We didn’t want to make a light, fruity Chardonnay.

“Now if you take Blocks 19 and 20 that have

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,