Josh Jensen's Calera Wine Company produces consistently praiseworthy Pinot Noir from four single vineyards on Mt. Harlan.

A Conversation With Josh Jensen:

The Original ‘Soilest’

It’s All About the Limestone.

by

Alan Goldfarb

June 10, 2008

n the early 1970s, Josh Jensen, freshly returned from Burgundy and the northern Rhône, traipsed through California stopping to pour hydrochloric acid on the ground to see if it would react with alkaline chalk in the soil. At last, one day, high up on one of the remotest and rugged spots imaginable, the sought-after reaction occurred, which meant that Jensen had hit upon one of the only limestone deposits in the state.

n the early 1970s, Josh Jensen, freshly returned from Burgundy and the northern Rhône, traipsed through California stopping to pour hydrochloric acid on the ground to see if it would react with alkaline chalk in the soil. At last, one day, high up on one of the remotest and rugged spots imaginable, the sought-after reaction occurred, which meant that Jensen had hit upon one of the only limestone deposits in the state.

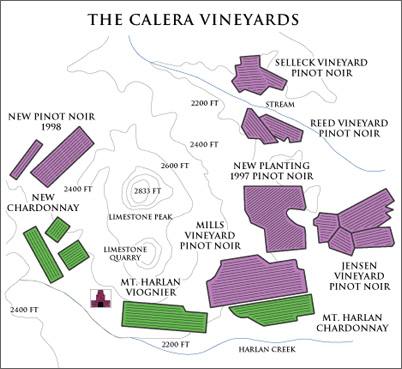

He thought then - and after 33 years he still believes - that this is the spot most hospitable to grow Pinot Noir. The actual location is at more than 2,200-foot elevation on Mount Harlan near Hollister (in the Gavilan mountains that bifurcate Monterey from San Benito counties),

For years, Josh Jensen has been making some of the best and most unique Pinot, Chardonnay and Viognier in America at his Calera Wine Company, without benefit of electricity, phones or much rainwater. You could call him a true soilest.

For years, Josh Jensen has been making some of the best and most unique Pinot, Chardonnay and Viognier in America at his Calera Wine Company, without benefit of electricity, phones or much rainwater. You could call him a true soilest.

The lanky 64-year-old believes that, “Clay (which comprises much of California’s vineyards) makes dull wine. Calcareous soils (limestone) give great finesse and complexity, nuance, and subtleties.

“… If you have a glass of apple juice, it has one message in it. It says, ‘I’m apple juice.’ If you have one of the world’s great wines, you taste a primary flavor that says this is a really good red wine and then you taste secondary and tertiary elements, other aspects of flavor. For an agricultural product, that’s really rare. It doesn’t just say Pinot Noir.”

These characteristics – grown in four distinct vineyards that ring Mount Harlan – make Calera’s wines dark in color, deep in flavor, and big in tannins that usually don’t come around for at least five years, and more likely a decade.

That flies in the face of today’s winemaking culture, in which “accessible”, as a euphemism for instant gratification, is de rigueur. But fashionable is precisely what Jensen – as erudite and sophisticated a man as you’ll find – is certainly not. I’ve known him for many years, even sharing high school basketball games in San Francisco with him as we watched his son and my unofficial “little brother” play, and I can say, without equivocation, that Josh Jensen is one of the world’s wonderful iconoclasts.

That flies in the face of today’s winemaking culture, in which “accessible”, as a euphemism for instant gratification, is de rigueur. But fashionable is precisely what Jensen – as erudite and sophisticated a man as you’ll find – is certainly not. I’ve known him for many years, even sharing high school basketball games in San Francisco with him as we watched his son and my unofficial “little brother” play, and I can say, without equivocation, that Josh Jensen is one of the world’s wonderful iconoclasts.

Opinionated, too? You bet. For instance, what he thinks about U.S. Pinot Noir – save for his own, of course – is that it’s worth nary a bother.

“In the past 10 years the style of American Pinot Noir has been blockbuster sledgehammers,” he begins, revving up. “They’re darker than any red Burgundy and with explosive fruitiness. Put one of our single-vineyard Pinots (next to them) and it gets steamrolled. But I’ve seen signs of movement back to complexity next to these vulgar flamethrowers.”

And what of Viognier, the northern Rhône variety of which he was one of the first in ’89 to introduce to California? “It is out of fashion, (but) we’re seeing signs of life,” he tells me. But when I tell him that there isn’t much Viognier being produced now after a brief but robust flurry in the early ‘90s, he says. “You want to know what happened to Viognier?”

“Grüner (Veltliner), Pinot Gris, Riesling, and Albariño.” That’s what happened to Viognier. “Five, ten years ago there were five Viogniers on wine lists. Today, they have sections called ‘aromatic whites.’”

When I suggest that what really killed Viognier was that producers were drowning it in too much new oak and rendering it too sweet, he concurs.

“From Day One, we have zero new oak in our Viognier", he responds. “We use 12-, 13-year-old French (barrels). We go to great lengths

not to add a single iota of oak-taste or odor.” His Viognier is also grown in limestone. The calcareous-soiled Pinots come from four vineyards:

Selleck’s 4.8 acres are the rockiest. The vineyard contains more limestone than the others and yields only a little more than a ton per acre. Planted in ’75, these wines are usually the most complex and dense of the four. Flavors are deep with black fruit, and the wine seems to have the greatest aging potential.

not to add a single iota of oak-taste or odor.” His Viognier is also grown in limestone. The calcareous-soiled Pinots come from four vineyards:

Selleck’s 4.8 acres are the rockiest. The vineyard contains more limestone than the others and yields only a little more than a ton per acre. Planted in ’75, these wines are usually the most complex and dense of the four. Flavors are deep with black fruit, and the wine seems to have the greatest aging potential.

The Jensen Vineyard, also planted in ’75, has 13.8 acres. It’s divided into four blocks, each on a hillside with a different exposure. It yields about 1.5 tons to the acre of very intense berry fruit.

Reed is located on a north/northeast facing hillside and is generally the last vineyard to ripen. Also planted in ’75, the wines are forward and aromatic, showing a less dense style than the other Pinots.

Then there’s the Mills. The largest of the Pinot vineyards at 14.4 acres, Mills was planted in ’84 on its own roots. Pinot from here has fragrant, spicy, cedar-like aromas, with underlying cherry and red berry fruit. The wines have a long finish, showing broad, round tannins.

I ask Josh if it’s possible to have real terroir in California. It’s a concept I feel is lost with the commoditization of wine. But he’s less pessimistic than I. “Of course,” he answers. “If there is such a thing as a terroir vineyard, ours are it. If terroir exists, it’s our vineyards. The wines are never combined. It’s present and accounted for at our sites.

“It will come more and more as time goes by. With more regional specialization, people will say, ‘Jesus, there’s one batch we get every year from this one spot that makes great wine.’ And one of these years they’ll make separate wine.

Josh Jensen pours vineyard manager Jim Ryan a glass of the Pinot Noir produced from the Ryan Vineyard in which they stand.

How about you, I ask. Why did you end up in such a remote spot? “When people want to start a winery, they want glamour,” he says. “They don’t want to live down here in cattle country. They want to be where the French Laundry (the Napa Valley restaurant) is and want to go to fashionable parties with other millionaires.

“But it was all about the limestone. … It does seem, in some ways, it’s the proximity to limestone that makes the great Burgundians so great. Let’s hope it does it in California.”

Photos and map courtesy of Calera Wine Company

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,