Altitude and latitude are just some of the factors that determine where grapes grow best.

The Coolness Factor:

Rethinking Where Varietals Grow Best

When cool climate grapes grow in a warm climate area and produce spectacular wine ostensibly atypical of that area, the question arises: “So just what defines a so-called cool climate?” Dan Berger runs hot and cold on the answer.

by

Dan Berger

August 7, 2008

scheduled breakfast meeting in August 1986 with wine makers in Washington’s Columbia Valley created a fascinating awakening for me. Over the last few years, that moment has come back to me in three dimensions, and from this I think I understand an aspect of terroir that was missing until now.

scheduled breakfast meeting in August 1986 with wine makers in Washington’s Columbia Valley created a fascinating awakening for me. Over the last few years, that moment has come back to me in three dimensions, and from this I think I understand an aspect of terroir that was missing until now.

My trip to Washington 22 years ago had begun a few days earlier when I drove into Seattle well past 9:30 in the evening. As I was parking the vehicle behind a hotel, I glanced west and saw the rays of the sun splayed across the sky, remnants of a gorgeous sunset. I asked the hotel desk clerk what time sunset was. He said about a quarter past nine.

And I realized that this far north in the United States sunlight hours on grapevines are greater during the summer months than they are in California. That affects things such as veraison, sugar accumulation, and most critically, flavor development in wine grapes. More sunlight equals a different sort of development of the grapes. That was where my thinking ended.

Days later the second revelation occurred. Overnight it had been cold enough in the Columbia Valley that I had to turn on the heat in my motel room. The next morning at about 10 A.M., as I left the Richland, Wash., motel and headed for my

Riesling grapes do best in cool climates so why do they shine in the warm Clare Valley of Australia?

But these two factors have led to some recent revelations about what constitutes a cool growing climate for wine grapes. I was spurred to think more seriously about this following a wine column I penned not long ago in which I wrote of the Clare Valley in Australia, calling it a cool-climate region that was perfect for growing Riesling.

An old friend who writes for a major wine magazine wrote to correct me. “Clare is not a cool region,” he wrote. “It’s warm.” He added, as proof, that some of the gutsiest red wines in Australia come from the Clare.

That brought back to mind a visit to the Clare two years ago in which the noon temperature was pretty hot (I’d guess it was above 90°). So, sure, I know that’s not a cold climate. And neither is Columbia Valley. And yet both regions are famed for their classic Rieslings, and it is well known that Riesling doesn’t make classic wine in a hot region.

But a number of factors enter the picture. As a starter, here’s a case example. I have long judged at the Mendocino County Fair wine competition in “cool” Anderson Valley, that gorgeous side valley of Mendocino County. That event almost always takes place in early August outside Boonville, and the temperature there at that time of year almost always gets close to the century mark. It is hot. Really hot, and stays so for many days.

Anyone experiencing this is likely to ask, “Cool climate?” and answer it, “No way!”

Yet proof that it is cool enough comes from the fact that despite high daytime temperatures, such superb wines as Riesling and Gewurztraminer do brilliantly, as do the cool-preferring Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. They can’t be grown terribly successfully in a hot climate.

Back to the rest of the story of my recent visit to the Clare: Following the searing heat of mid-day, the afternoon experience was a major turnaround. Cool breezes from the north raced south through the vines. And by 5 p.m., I was racing to the rental car for a jacket. By 7 p.m., it was so cold a fire was started in the fireplace! And this was summer.

A Growing Degree Days System That’s Too Simplistic

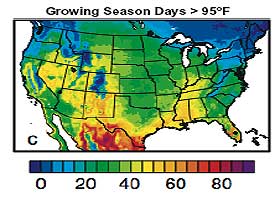

So it is apparent that, decades ago, when UC Davis developed a five-tier system for determining the appropriate places to grow wine grapes (and additional data showing temperature zones for table grapes and raisins), it was using a premise that worked reasonably well for that time. But it had drawbacks. One was that it was too simplistic.Then that system was refined with the use of Growing Degree Days (GDD), which looks at accumulated temperature units throughout a season. This relates

Between now and 2100, the climate will change drastically, which will alter growing seasons no matter where you live. But for now, there’s no guarantee that cool climate grapes can’t fare well in warmer regions.

As a result, we now know that the Carneros area in south Napa and Sonoma counties is cooler (less than 2,500 GDD) than are both counties’ upper valleys, and, as such, it is better suited for Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Merlot, and sparkling wines. We also know that grapes like Syrah can ripen in Carneros and other cool regions, and indeed, in Australia, the cool regions of northern Victoria make some of the most prized cool-climate red wines.

By contrast, the central valley areas of California, with GDD readings of 3,500 or greater, usually produce low-acid, high-sugar grapes that produce wines that can be soft and lacking in much character.

Worldwide, the higher you go in altitude the cooler you get, based on lower average temperatures. So, for instance, the Eden Valley of Australia may be within the bounds of (warm climate) Barossa, but its altitude makes it a superb place to grow Riesling. It’s a lot cooler than the rest of the surrounding region.

However, there are curious exceptions. One of them is the Mendocino Ridge appellation in Anderson Valley of Mendocino County. Much of Anderson Valley, like the Russian River appellation, gets overnight and morning fog that keeps nighttime temperatures very low. And unlike Columbia Valley, which warms quickly from the cold nights, Anderson Valley remains cool until 11 a.m. or so.

Above the fog layer, however, there are mountaintop mesas that are actually a bit warmer on average than the valley floor in accumulated warmth. The Mendocino Ridge appellation was created just for those properties located at least 1,200 feet above the valley floor, thus appearing like islands in the sky above the fog line. Despite the altitude, they are warmer areas than is the valley floor, but still cooler than some areas because of the maritime and altitude impacts.

Much of the above material now is part of formal climate research in Australian and Canadian viticultural circles. (The Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research just published a scientific paper called “Climate drivers of red wine quality in four contrasting Australian wine regions.” And an entire department has been established at Brock University in Canada called the Cool Climate Oenology and Viticultural Institute.)

A key factor in this quest to define “cool climate” viticulture relates to the coldness of the nights in a region and how wide a day-night swing is the temperature range. In the Clare, for instance, daytime summer temperatures well above

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,