While this close-up of Valle de Guadalupe vineyard in Mexico might suggest Tequila production would be a safer choice, you might be surprised at the quality of wine made now.

International (Country Appellation)

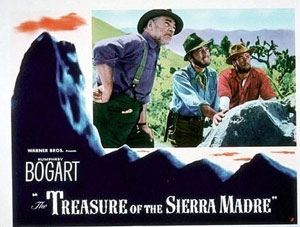

The Treasure of the Guadalupe

The Rise of Mexican Wineries

The Mexican wine industry as a full-scale marketing entity is still in its infancy. But the quality of some its wines suggests that it is only a matter of time before it successfully get their act together.

by

Alan Goldfarb

September 3, 2008

t must have been about 20 years ago – when the American Viticultural Area (AVA) system was in its nascent stages – that Cecil DeLoach forcefully parried a wine journalist who suggested, “Your wines will never be accepted in the world market unless they exhibit a sense of place.”

t must have been about 20 years ago – when the American Viticultural Area (AVA) system was in its nascent stages – that Cecil DeLoach forcefully parried a wine journalist who suggested, “Your wines will never be accepted in the world market unless they exhibit a sense of place.”

On that day, at a seminar attended by mostly Sonoma County winemakers and vintners, DeLoach, who founded and sold DeLoach Vineyards and started Hook & Ladder winery west of Santa Rosa, stood to attention and said: “I’m an ex Marine and nobody is going to tell me what to plant where!”

In inimitable American fashion, DeLoach swatted away the notion of the French-style government regulation to which the wine writer – with Francophile proclivities - was alluding.

DeLoach seemed to be saying: I’m an American and unlike the French and Italians, the government has got to have big ones if it thinks I can’t plant Cabernet here and Chardonnay there.

And so it’s becoming clear that those in the wine industry in Mexico - which is going through some kind of “silent revolution,” as one ex-pat American down there observed – will rebuke the recently suggested government regulation.

And so it’s becoming clear that those in the wine industry in Mexico - which is going through some kind of “silent revolution,” as one ex-pat American down there observed – will rebuke the recently suggested government regulation.

Of course they will. Consider the penchant of the Mexican citizenry for fending off government regulation of most kinds with such anarchistic verve as though it was a futbol game that really, really mattered.

As illustration, remember Alfonso Bedoya’s clichéd bandito character in “The Treasure of Sierra Madre” when he uttered to the gringos, in a very bad English/Mexican dialect, “I don’t have to show you any stinkin’ bah-jes.”

As illustration, remember Alfonso Bedoya’s clichéd bandito character in “The Treasure of Sierra Madre” when he uttered to the gringos, in a very bad English/Mexican dialect, “I don’t have to show you any stinkin’ bah-jes.”

The timing is important. At the precise moment when Baja California Norte’s wine industry - which contains within its boundaries Mexico’s most important region, the Valle de Guadalupe – is emerging, strict Denomination of Origin (DO) controls would hamstring it.

There is a growing push back to any type of DO, just as the Guadalupe Valley’s winemakers are trying to figure out what kind of wines they are going to make, and what types of varieties are best suited to their climate.

I’ve tried some of the wines. Nebbiolo, Tempranillo, and Chenin Blanc show wonderful potential right now. They are grown about 70 miles south of the U.S.

”There’s gold in them hills!” Only now the gold is grape vines as Mexico expands its wine production.

However, an AVA system that’s in place just across the border – or, rather an MVA (Mexican Viticultural Area) plan - will serve the industry better. While it’s not the best solution (after all, in the U.S., AVAs are mostly about marketing, although more definitive appellation distinctiveness is emerging organically), the producers of Guadalupe need more time to sort out the puzzle, and in their own time .

MVAs would suffice for the nonce, and they would go a long way toward showing the rest of the world that the Mexicans are going about their business in a thoughtful and more meaningful manner.

But in order to advance further, several very real obstacles have to be pushed aside. To wit:

<<>>Bordeaux and/or Rhône reds will have to find a better measure of success;

<<>>Import regulations into the U.S. (remember NAFTA?) have to be loosened;

<<>>And the stifling tariffs put on by Mexico’s authorities have to be reduced.

Buying wine at a restaurant in Mexico is a hair-raising proposition. So high are the taxes that a simple bottle of Valle de Guadalupe Chenin, for instance, will run you about 50 bucks.

Some of the producers of Guadalupe, with whom I’ve been corresponding, vociferously agree that a DO at this time is not a good thing. As Dr. Hans P Backhoff of Monte Xanic, one of the largest producers in Mexico, and the presidente de la Asociacion de Viticultores de Baja California, expressed it to me in an e-mail:

“Although we have been making wine for centuries, it was only in 1970 that the first Cabernet Sauvignon was produced in Baja California. That shows how new we are from the oenological point of view. The first step that we need to do is to define the limits of each valley (Baja California, Guadalupe, Santo Tomas San Vicente, Ojos Negros, Tecate, and de las Palmas). The government at the moment has a very serious challenge, which is to define the use of the land.”

When asked if an MVA system would work better, Backhoff replied, “Yes, I think you are right, we need more time to understand what’s happening. The government is waiting for our suggestions. We are working with weather, soil, water, and historic information to determine boundaries of the regions … (And) there are other states like Coahuila, Queretaro, Aguascalientes, Sonora and Zacatecas.”

Antonio Badan, proprietor of a small winery in Guadalupe, Mogor-Badan, was quite adamant in his response. “… It is premature to establish regulations for an industry that is still experimenting with what might be the best elements of its development,” he wrote, also in an e-mail. “In addition, I think there are much more pressing questions that need to be tackled. I shall mention the very poor management of water resources, the lack of proper land zonings that endanger the industry by allowing developments to encroach on agricultural lands, and the discriminatory U.S. laws that prevent our wines from crossing into America (one bottle from Mexico vs. 60 bottles from elsewhere).

Antonio Badan, proprietor of a small winery in Guadalupe, Mogor-Badan, was quite adamant in his response. “… It is premature to establish regulations for an industry that is still experimenting with what might be the best elements of its development,” he wrote, also in an e-mail. “In addition, I think there are much more pressing questions that need to be tackled. I shall mention the very poor management of water resources, the lack of proper land zonings that endanger the industry by allowing developments to encroach on agricultural lands, and the discriminatory U.S. laws that prevent our wines from crossing into America (one bottle from Mexico vs. 60 bottles from elsewhere).

“Fortunately, we have few problems selling our wines (mostly within Mexico and in Europe), so marketing is not a strong issue at the moment. Maybe, once we have consolidated the nature of our wine industry, and we have solved the problems that put into question its very existence, we can then establish regulations that oversee its consistency. Clearly, we need at least another 10 years to achieve that.”

Some have likened the Valle de Guadalupe to the Napa Valley in the 1970s, where it took about another 10 years for the AVA system to be put in place. It’s about the same time that Antonio Badan says he believes it will take to establish

some sort of regulation there. But - and this is not to be dismissed - the producers in Mexico have not achieved the level of internal cooperation that seemed to go a long way toward elevating the Napa Valley.

some sort of regulation there. But - and this is not to be dismissed - the producers in Mexico have not achieved the level of internal cooperation that seemed to go a long way toward elevating the Napa Valley.

In the meantime, exactly

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,