When is blind tasting too blind?

Wine Analysis by Region

I appreciate what APPELLATION AMERICA is doing with its Best-of-Appellation™ Evaluation Program in expanding the base of great wines by rigorously identifying and profiling regional distinctiveness, which should be central to defining quality, not an excuse for bad wine making.

by

Dan Berger

October 29, 2008

hen we taste a Sauvignon Blanc and are tempted to rank it very highly, we often determine it to be typical of its region. Such as a rating that heartily approves of the cut-grass, lime, gooseberry aroma of a Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc. Not just New Zealand, but more specifically Marlborough. This contrasts with the style of Sauvignon Blanc that isn’t as assertive in the gooseberry, but has a faint bit of tropical character, such as the Craggy Range of Martinborough. Or the even milder grass of Hawkes Bay. There is a difference, and Sauvignon Blanc purists would be pleased to suggest that all the various styles are valid, and that each area makes exceptional wines with differing characteristics that show evidence of their terroir.

hen we taste a Sauvignon Blanc and are tempted to rank it very highly, we often determine it to be typical of its region. Such as a rating that heartily approves of the cut-grass, lime, gooseberry aroma of a Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc. Not just New Zealand, but more specifically Marlborough. This contrasts with the style of Sauvignon Blanc that isn’t as assertive in the gooseberry, but has a faint bit of tropical character, such as the Craggy Range of Martinborough. Or the even milder grass of Hawkes Bay. There is a difference, and Sauvignon Blanc purists would be pleased to suggest that all the various styles are valid, and that each area makes exceptional wines with differing characteristics that show evidence of their terroir.

By contrast, tasted blind, I have often seen Sauvignon Blanc wines from the Sierra Foothills that deliver a mostly Graves-like character. Is this a

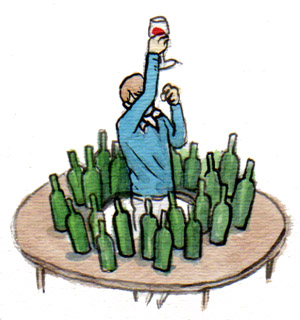

One reviewer once said he judged 20,000 wines a year. This means that he tasted 55 wines a day, every day of the year.

Then there is the Sauvignon Blanc with a touch of Loire herbal-ness. It may come from Dry Creek Valley, and the skilled judge with decades of experience can use a sense-memory to reflect back on the Dry Creek Sauvignon Blancs he or she has tasted over the years and watch the wine as it evolves in the glass and the bottle over time. Another Sauvignon Blanc comes along with more olive/grass/hay character. Could it be Russian River? That’s certainly what the cooler areas of Russian River yield in Sauvignon Blanc.

As is evident, the frame of reference becomes a key factor in visualizing different approaches with the same grape. And this is all terroir-driven, and it broadens the scope of fine wine we have access to. (However, when Sauvignon Blanc is put through a malolactic fermentation, or aged in oak, or subjected to other regimes, the terroir-ishness seems to be scalped.)

This regional sort of analysis should lead to discovery of a lot more interesting wine, and not what often happens: the most assertive wine gets the top score and the others take the caboose. With the vast majority of those who evaluate wine, such regional distinctions may not be a germane issue, but they have a real place in the world of wine. This is most important when the competition is not a regional one, but a national or international event.

How many times have we seen reviewers speak of a Pinot Noir as having Burgundian character, or a Bordeaux as being rich enough to be Napa-like? It happens all the time and we are, in most all cases, speaking of the region as the key element that gives a character we recognize and one that contributes to a wine’s quality.

When judgings are done in which the general region is known (such as at the Sonoma County Harvest Fair wine competition, at which I often judge), we know the fruit in the wines all came from Sonoma County. This may not seem much of an advantage in determining quality, since Sonoma is such a vast region, but it can be.

Disclosure of Origin

Knowing the region does a lot for a blind tasting. For instance, it helps the taster to justify an element that he or she might originally think to be “out of left field,” and thus aberrant. This is especially true if a particular characteristic (such as black pepper in Cabernet Sauvignon or red currant in Cabernet Franc) begins to show up in more than one wine in the evaluation. When such characteristics are replicated in disparate wines (such as the black pepper we see in numerous red-wine varieties grown in British Columbia’s Naramata Bench), we can ascribe to that character a regional basis.In some competitions where the judges are not even told the varietal being judged, the evaluator is really at a loss to determine if a wine is displaying the proper characteristics for the wine type it is supposed to be. This is one reason, for example, why categories of wine that say “blended red wines” and no other identifier, are so hard for any judge to properly evaluate. It is one of the ways that

judgings in Europe can be confounding. One basic tenet of such evaluations is: “Here is a white wine. We will tell you nothing else about it. It’s your job to state whether it is a great wine or a poor wine.” What a nightmare. Is it a Chardonnay that smells like Riesling, or is it an oaky Riesling?

judgings in Europe can be confounding. One basic tenet of such evaluations is: “Here is a white wine. We will tell you nothing else about it. It’s your job to state whether it is a great wine or a poor wine.” What a nightmare. Is it a Chardonnay that smells like Riesling, or is it an oaky Riesling?

But look at the way many if not most wine consumers buy wine: by number. Rating wine by numbers, a popular sport among many people around the world, is rife with fallacies, many of which were outlined decades ago by the late Prof. Maynard Amerine at the University of California at Davis.

In a book called Wines: Their Sensory Evaluation, Amerine listed a few of the common fallacies inherent in blind evaluation of wine. That chapter in the book also hinted at how to avoid some of the problems. In normal circumstances, it’s difficult to avoid some complications, and doing so is often time-consuming.

One element that Amerine and co-author Maynard Roessler failed to touch upon (partially because it had little to do with what the book was all about) was the vital reason that wine should be tasted blind with at least a small bit of additional information given to the evaluators. I suggest that knowing the region from which a wine comes is vitally helpful in determining the level of quality a wine displays - especially if the goal of the tasting is to determine how regional character plays a role in quality. To try to do so after the fact seems a bit like inverting the process. Indeed, if the purpose of an evaluation is to simply see which wine has the most oomph, regional character is a non-issue.

A famous wine critic, one famed for not tasting wine blind, once stated as a fact that saying a wine displayed terroir was nothing more than excuse for making bad wine. This naïve statement ignores one of the elements that have made show judgings in Australia as interesting as they are. And it’s one of the reasons that some European competitions fail the ultimate test: relevance. It’s also why people spend what they do on Bordeaux – why, for instance, St. Julien is considered to be a “better” region than is Blaye.

Too Much Information

Those who evaluate wine with sight of the label have data on which to base a score that has nothing to do with the liquid. Knowledge of the price and other factors about a wine (including

Knowledge of the price and other factors about a wine (including

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,