White Oak Vineyards makes a popular blueberry wine but also produces grape varietals such as Norton and Muscadine.

While a vintner awaits PD resistant vines, it’s fruit

forward in Alabama

by

Alan Goldfarb

December 30, 2008

andal Wilson knows from dirt about as well as he knows his terrain. Finding himself relocated to northeast Alabama because of work, the Cal Poly (San Luis Obispo) agriculture and soil science graduate has parlayed that knowledge into a tiny parcel in the Choccolocco Valley (chok o locko) where he makes wine mostly from blackberries and blueberries.

andal Wilson knows from dirt about as well as he knows his terrain. Finding himself relocated to northeast Alabama because of work, the Cal Poly (San Luis Obispo) agriculture and soil science graduate has parlayed that knowledge into a tiny parcel in the Choccolocco Valley (chok o locko) where he makes wine mostly from blackberries and blueberries.

While Wilson hopes that the blueberry wine will translate to big sales in commodity starved Cuba (more about that later), he frets that his vineyard, located about 65 miles east of Birmingham, isn’t situated in a place that’s conducive to vinifera grapes (European varieties used for fine wine).

So, he makes due with the fruit wines. Wilson also sells varieties for his Southern Oak Wines brand, which are on their own rootstocks, and trained on VSP (vertical shoot positioned), double-cordon and bi-lateral cordon trellis systems. For instance, Norton - arguably the only true American red, which does well primarily in Missouri and Virginia. Also made at Southern Oak are Villard Blanc,

Winemaker and owner of White Oak Vineyards in Alabama, Randal Wilson

Because of the climate 10 miles east of Anniston where his White Oak Vineyards is located, vinifera would be susceptible to Pierce’s disease (PD), which is spread by the bacterium from the sharpshooter insect.

“There’s a little elevation (here), which helps a lot, and little shade, with well-drained soils,” the 55-year-old Wilson tells APPELLATION AMERICA without much prompting. “It’s an interesting dry climate with a little bit of humidity but drier than the Gulf Coast.”

Cheaha Mountain in the southern tip of the Appalachians also keeps the region a bit cooler as compared to the rest of the southeast. Thus, Wilson bides his time making about 2,000 cases a year from the aforementioned varieties from 5 ½ acres that were planted 10 years ago. Additionally he produces Chambourcin, a red French hybrid; Chardonel, a cross between Chardonnay and Seyval Blanc; and Muscat Alexander (the grapes for the latter coming from California).

Wilson picks the grapes for those wines at from 22 to 25 degrees Brix (a measure of sugar), sometimes chaptalizing (adding legal amounts of sugar) and aging the wines in plastic tanks and, where appropriate, adding French alternatives (oak products instead of utilizing expensive barrels).

He also makes a Cabernet Sauvignon from fruit shipped from California, from Lodi “and other places I don’t know.”

But, oh, how he champs at the bit to be able to grow his own Cabernet or Merlot. Toward that possibility, he says he anxiously awaits UC Davis’ experimental trials with PD-resistant vines.

“As soon as those are available, I’m going to plant Viognier that will do good in our region of the world; and maybe the Spanish varieties – the hot climate grapes,” he declares.

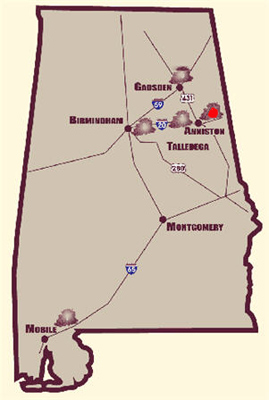

There are just a handful of wineries in Alabama located throughout the state and White Oak Vineyards in the northeast is marked with a red dot.

“I’d grow some here but PD gets us,” Wilson reiterates with lament in his voice. He further describes his land as being a “little too steep, but it’s not bottom land. It has ancient residual material with consolidated rock, and alluvial fans.”

He characterizes himself as “a grape grower, who’s been growing grapes up here for 10 years. It’s been hard the last 5-6 years because we went through the worst drought in the last 100 years, so I don’t know what’s normal anymore.

Last year Wilson says the region received only 22 inches of rain. “Normal” is 52 to 53 inches. “I’ll tell you what, if we can keep the deer (white tail) and the birds (cardinals, robins) out and keep PD off of it, we can grow some gorgeous grapes.”

The Cuban Blueberry Connection?

As for those fruit wines (“which I treat like any type of wine” and are “not all that different from (vinifera) grapes”), made with just 1- to 2-percent residual sugar, Wilson insists he likes making them. So much so that he hopes to one day land a big contract in Cuba.Wilson was quoted at the end of a very concise and long article that appeared in The New York Times Magazine (“The End of the End of the Revolution”, Dec. 7, 2008), saying that the Cubans “seem to prefer my blueberry wine, just loved that.”

But when we reached him by phone at his tasting room - where at least three customers came by in a 45-minute period - Wilson explained that, no, he hasn’t yet sold any blueberry wine to Cuba. But he was there on a trade mission in November, where he happened to bring along some of his wine.

What with Fidel Castro in his waning days and Barack Obama in his ascendancy, he hopes to cut a deal whereby Southern Oak wines – preferably blueberry – might someday work their way through the port of Mobile, along with telephone poles and poultry that Alabama already ships to that beleaguered island. In Cuba, where he sampled restaurateurs and government officials on his wine, he believes he came face-to-face with Raul Castro (“I smiled; he did, too.”), who’s apparently running the country in his brother’s stead.

“They liked it (my wine). It’s just good wine,” he said of the Cubans’ reaction. “The Cubans really liked the blueberry. The restaurants were crazy about blueberry. The (trade mission) buyers liked the Cab.”

So, did he cut a deal? “I gave them my card, I talked to them, and gave them samples of wine” he explains. “I suspect purchasing wine is low on the totem pole (so) I haven’t heard anything.” However, Wilson observed that, in some restaurants, there were wines from Chile, Argentina, as well as California. Among the California wines, in Havana, Wilson saw the Sonoma Cabernets of Gallo.

“My Cab is way better than those South American wines,” he says with a big laugh. “I put a lot of pride (into it). The grapes from California are perfect.”

“My Cab is way better than those South American wines,” he says with a big laugh. “I put a lot of pride (into it). The grapes from California are perfect.”

So, if the grapes from California are so pristine and he can’t or never will be able grow vinifera grapes, and considering that he went to school in California, why Alabama? “I wound up here with a job. The land here is beautiful. It’s a beautiful part of the world,” he says with an implied “but”. “I’m trying to make this fun, if it’s possible. But it’s hard wor

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,