Historic Hermann - Missouri

Hermann, Cake, and the Noble Savage

The Hermann appellation features improbabilities similar to its 'noble savage' Norton

by

Tim Pingelton

November 2, 2005

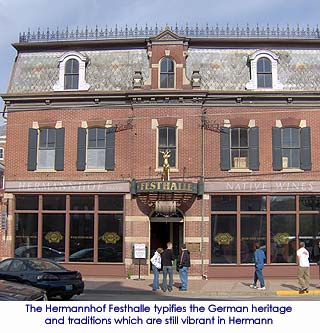

From early in youth, a special feeling came over me when I made a trip to the Hermann area in east central Missouri. My dad would drive us there from our home in the exact center of Missouri a couple times every fall to see the trees change. In Hermann proper, houses and buildings are perched just a few feet from the sidewalk, and every house has a few window boxes full of healthy pansies or chrysanthemums, as the season dictates. Residential streets are often at a seemingly 45° grade, and my dad always double-checked the parking brake on the Buick. There is often an elderly woman walking carefully down the sidewalk carrying a cake. Numerous church steeples rise along with plump oaks and walnuts. It is not unlikely to see a small grape press or fruit crusher sitting on a back porch. The feeling that came over me then was one of being somewhere markedly different, but different in a comfortable, welcoming, old-world way.

Now I know that the city design of Hermann is based on an old-world model. The climate in the Hermann AVA is almost identical to that stretching across the southern and eastern German wine regions of Württemberg, Franken, Saale-Unstrut, and Sachsen. The Hermann American Viticultural Area (AVA) is small, comprising only 51,200 acres. It is nestled in a bend on the southern bank of the Missouri River about 80 miles west of St. Louis. Precipitous river bluffs and graceful rolling hills make the area further resemble Germany’s Rhine Valley.

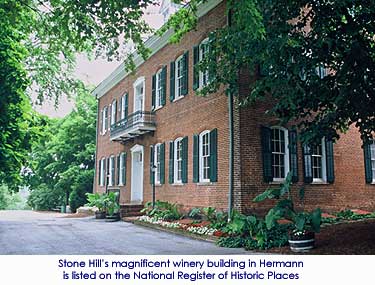

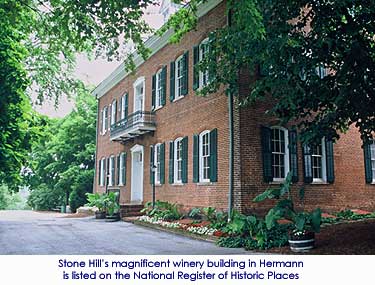

In the early 19th century, the largest area of German colonization in America was in Philadelphia. In the 1820s, a group called the German Settlement Society of Philadelphia sought to establish a German colony in the “Far West.” They selected a site in Gasconade County, Missouri and named it Hermann. Much of their effort in establishing a comfortable place to live involved the establishment of fine schools, and winemaking. And make wine they did. In his 1907 book on the German Settlement Society, William G. Bek wrote that, as of 1904, “the surplus number of gallons of wine Missouri produced is 3,068,780 gallons. Of this quantity, Gasconade County alone furnished 2,971,576 gallons. Almost all of this amount was produced at Hermann, or its immediate surrounding country districts.” Indeed, around the turn of the century, the Stone Hill Wine Company in Hermann, Missouri, was the second largest winery in the nation and the third largest in the world. Thirty years before Bek’s book, German immigrant to Missouri Gert Goebel declared, “Hermann can be called the cradle of winemaking in Missouri.” Prohibition and rapidly changing demographics caused a severe drop in area wine production, but the last 30 years have seen a strong renaissance in winemaking in the Hermann AVA.

Almost all of this amount was produced at Hermann, or its immediate surrounding country districts.” Indeed, around the turn of the century, the Stone Hill Wine Company in Hermann, Missouri, was the second largest winery in the nation and the third largest in the world. Thirty years before Bek’s book, German immigrant to Missouri Gert Goebel declared, “Hermann can be called the cradle of winemaking in Missouri.” Prohibition and rapidly changing demographics caused a severe drop in area wine production, but the last 30 years have seen a strong renaissance in winemaking in the Hermann AVA.

Is it a mere coincidence that Concord, the name of the ship that brought the first German immigrants to America in 1683 is also the name of the grape so widely planted by descendants of those emigrants in the Herman AVA? Many acres of Concord are still planted in this area, made either into grape jelly and preserves or sweet, foxy Concord wine. A much more interesting grape is heavily planted in the Hermann area, though. Again quoting his 1907 book, Bek writes, “The Virginia Seedling, the Concord and the Delaware and other kinds had [by 1865] proven their hardiness to withstand Missouri’s changeful climate.” This “Virginia Seedling,” in that time also called “Norton’s Virginia Seedling,” is now known to Missouri wine drinkers as Norton. Other regions in North America might call this grape “Cynthiana,” but in Missouri it is Norton.

There is a perception among many wine aficionados that Norton makes a more full-bodied wine apt for long aging, where Cynthiana (what Virginians almost exclusively call this grape) is somewhat lighter and more suitable to be consumed young. Norton and Cynthiana ripen at different times, and genetic testing has proven that they are not 100% similar. An excellent article on the grape and its founder written by Clifford and Rebecca Ambers in the Fall, 2004 American Wine Society Journal suggests that Cynthiana is a sport, or mutation, of Norton.

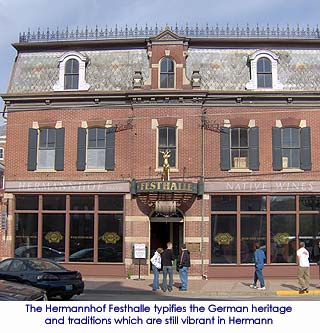

Other popular grapes grown in the Hermann appellation include Traminette, Chardonel, Seyval, Vidal, Catawba, Chambourcin, and St. Vincent. It is said that many visitors to wineries in this region and throughout Missouri talk dry but buy sweet. This may or may not be true, but the local wines here cover the tasting spectrum. Stone Hill Winery, the third largest in the world at the turn of the last century, is still the region’s largest producer clearly leading the area in production. Their Norton is dry and lively, and their list of awards won is lengthy. Stone Hill also boasts the largest series of underground cellars in North America. Other area wineries are the Adam Puchta Winery (which recently celebrated its 150th year of continuous family-owned operation), the Röbller Winery, Bias Vineyards & Winery , Hermannhof Winery (with ten stone cellars in the “French” part of Hermann), and Oak Glenn Vineyards & Winery. As a whole, these wineries have helped move the hybrid and native grapes from vinifera (or old-world European) substitutes to quality wines with their own unique character.

Norton can be a bear to work with, however. The heavy amount of suspended solids in Norton juice can lead to false sugar readings in the vineyard or in the lab. I recently spent a Saturday clipping bunches of Norton at a vineyard in mid-Missouri. The grapes did not taste sweet but had a woody, bitter taste. The smell was similar to the smell of a wadded-up green leaf: fresh, but not something suitable for wine production. The refractometer, a field device used to determine sugar content in grapes by measuring the refraction of light through a drop of juice, showed 24% (or brix) sugar, which

Now I know that the city design of Hermann is based on an old-world model. The climate in the Hermann AVA is almost identical to that stretching across the southern and eastern German wine regions of Württemberg, Franken, Saale-Unstrut, and Sachsen. The Hermann American Viticultural Area (AVA) is small, comprising only 51,200 acres. It is nestled in a bend on the southern bank of the Missouri River about 80 miles west of St. Louis. Precipitous river bluffs and graceful rolling hills make the area further resemble Germany’s Rhine Valley.

In the early 19th century, the largest area of German colonization in America was in Philadelphia. In the 1820s, a group called the German Settlement Society of Philadelphia sought to establish a German colony in the “Far West.” They selected a site in Gasconade County, Missouri and named it Hermann. Much of their effort in establishing a comfortable place to live involved the establishment of fine schools, and winemaking. And make wine they did. In his 1907 book on the German Settlement Society, William G. Bek wrote that, as of 1904, “the surplus number of gallons of wine Missouri produced is 3,068,780 gallons. Of this quantity, Gasconade County alone furnished 2,971,576 gallons.

Almost all of this amount was produced at Hermann, or its immediate surrounding country districts.” Indeed, around the turn of the century, the Stone Hill Wine Company in Hermann, Missouri, was the second largest winery in the nation and the third largest in the world. Thirty years before Bek’s book, German immigrant to Missouri Gert Goebel declared, “Hermann can be called the cradle of winemaking in Missouri.” Prohibition and rapidly changing demographics caused a severe drop in area wine production, but the last 30 years have seen a strong renaissance in winemaking in the Hermann AVA.

Almost all of this amount was produced at Hermann, or its immediate surrounding country districts.” Indeed, around the turn of the century, the Stone Hill Wine Company in Hermann, Missouri, was the second largest winery in the nation and the third largest in the world. Thirty years before Bek’s book, German immigrant to Missouri Gert Goebel declared, “Hermann can be called the cradle of winemaking in Missouri.” Prohibition and rapidly changing demographics caused a severe drop in area wine production, but the last 30 years have seen a strong renaissance in winemaking in the Hermann AVA.

Is it a mere coincidence that Concord, the name of the ship that brought the first German immigrants to America in 1683 is also the name of the grape so widely planted by descendants of those emigrants in the Herman AVA? Many acres of Concord are still planted in this area, made either into grape jelly and preserves or sweet, foxy Concord wine. A much more interesting grape is heavily planted in the Hermann area, though. Again quoting his 1907 book, Bek writes, “The Virginia Seedling, the Concord and the Delaware and other kinds had [by 1865] proven their hardiness to withstand Missouri’s changeful climate.” This “Virginia Seedling,” in that time also called “Norton’s Virginia Seedling,” is now known to Missouri wine drinkers as Norton. Other regions in North America might call this grape “Cynthiana,” but in Missouri it is Norton.

There is a perception among many wine aficionados that Norton makes a more full-bodied wine apt for long aging, where Cynthiana (what Virginians almost exclusively call this grape) is somewhat lighter and more suitable to be consumed young. Norton and Cynthiana ripen at different times, and genetic testing has proven that they are not 100% similar. An excellent article on the grape and its founder written by Clifford and Rebecca Ambers in the Fall, 2004 American Wine Society Journal suggests that Cynthiana is a sport, or mutation, of Norton.

Other popular grapes grown in the Hermann appellation include Traminette, Chardonel, Seyval, Vidal, Catawba, Chambourcin, and St. Vincent. It is said that many visitors to wineries in this region and throughout Missouri talk dry but buy sweet. This may or may not be true, but the local wines here cover the tasting spectrum. Stone Hill Winery, the third largest in the world at the turn of the last century, is still the region’s largest producer clearly leading the area in production. Their Norton is dry and lively, and their list of awards won is lengthy. Stone Hill also boasts the largest series of underground cellars in North America. Other area wineries are the Adam Puchta Winery (which recently celebrated its 150th year of continuous family-owned operation), the Röbller Winery, Bias Vineyards & Winery , Hermannhof Winery (with ten stone cellars in the “French” part of Hermann), and Oak Glenn Vineyards & Winery. As a whole, these wineries have helped move the hybrid and native grapes from vinifera (or old-world European) substitutes to quality wines with their own unique character.

Norton can be a bear to work with, however. The heavy amount of suspended solids in Norton juice can lead to false sugar readings in the vineyard or in the lab. I recently spent a Saturday clipping bunches of Norton at a vineyard in mid-Missouri. The grapes did not taste sweet but had a woody, bitter taste. The smell was similar to the smell of a wadded-up green leaf: fresh, but not something suitable for wine production. The refractometer, a field device used to determine sugar content in grapes by measuring the refraction of light through a drop of juice, showed 24% (or brix) sugar, which