“The state of Missouri apparently is the area in which the good red wine is produced.” ~ Father Münch, c. 1865

Salubrious Missouri

It may be due to a Midwestern temperament or to a wide-open market, but secrecy and hostile competition are not found in Missouri wineries.

by

Tim Pingelton

December 20, 2005

In a letter featured in the 1817 book The Emigrant’s Guide to the Western and Southwestern States and Territories, Mr. G. Sibley, of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, writes,

Salubrious means "that which promotes health or well-being."

Salubrious means "that which promotes health or well-being."

In the St. Charles [MO] Democrat, Father Münch offered his impression on this wild western state: "The state of Missouri apparently is the area in which the good red wine is produced." Father Münch wrote this nearly 50 years after Mr. Sibley’s letter, and Missouri had made major advances in winemaking in those 50 years. In that time, European emigrants (heeding Mr. Sibley’s sage advice?) came to this area by the wagonload. They settled along the Missouri River in St. Louis and further up the river in towns like Augusta and Hermann. They printed newspapers in German, established fine schools, planted grape vines, and made wine. Near the turn of the century, the Stone Hill Wine Company in Hermann was the second largest winery in the nation and the third largest in the world.

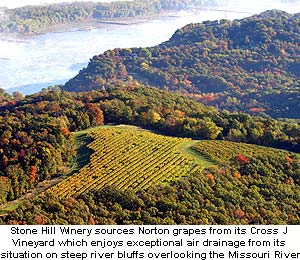

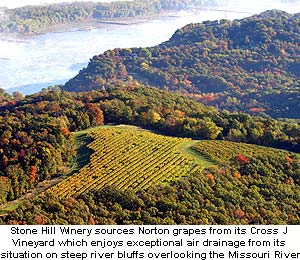

Stone Hill Winery today produces high quality wine, and the Adam Puchta Winery (also in Hermann) recently celebrated 150 years of uninterrupted family winemaking. Hermann’s Oak Glen Winery owns 5 or 6 rows of Norton vines originally planted in the 1850s. That very Norton could be the wine Father Münch wrote about, although it was called Virginia Seedling or Virginia Sämling in his time.

Hermann and Augusta are not the only winemaking areas in the state, however. In total, around 50 wineries exist in Missouri. Most are located within 30 miles of the Missouri River, but a dozen others dot the state, mainly south of the River. The boundaries of the huge Ozark Mountain Viticultural Area lasso over half of the state’s wineries, and the Augusta and Hermann sub-appellations corral about one-fourth of those.

From the Illinois and Iowa Deep Loess and Drift, to the Southern Mississippi Alluvium, to the Springfield Plain, to the Central Claypan Areas, soil and climate conditions of the Missouri state appellation vary greatly. Bedrock ages span from the Precambrian era (near Ste. Genevieve) to Tertiary and Quaternary eras (along the Missouri River). This translates alluvial soil in the river areas, loess and clay in the prairie areas, and rocky soils on the hills. The myriad microclimates, growing and vinifying practices, and cultivar selections produce a wide array of wine styles and quality. Missouri wines cannot be made anywhere but in Missouri.

Streets and highways throughout Missouri are generally in rough shape. Heaving in the frigid winters and kinking in the steamy summers create potholes and cracked asphalt. These extreme climactic conditions call for viticultural diligence and careful rootstock selection. Many vineyard workers set down their pruning shears on a Friday in late winter only to pick up the planting shovel on the next Monday in early spring.

It may be due to a Midwestern temperament or to a wide-open market, but secrecy and hostile competition are not found in Missouri wineries. The first thing you hear when you enter a winery in Missouri might be “I’m glad you found us.” Chances are that you, too, will be glad you found them. The agricultural abilities of many farmers-turned-vintners are evident in their clean fruit, and subsequently, in their pleasingly unexpected wines. As you turn onto a gravel drive leading to a Missouri winery, you might see a bunch (herd?... flock?) of alpacas or miniature horses roaming around the neighboring ranch. But Missouri is not all cows and sweet wine blends. You may well be surprised at the large-winery quality of the Chardonel at a small winery; just as you might be surprised at the boutique-winery taste of the Seyval Blanc at a large winery. Missouri has great Champagne, port, and sherry, too.

In my ongoing travels to taste wine in every winery in the state of Missouri, I do a lot of driving. Always about one decade behind the times, I play a lot of cassette tapes as I tootle down two lane blacktop roads to the next tasting room. I am completely crazy about Cuban, Puerto Rican, and African music. “African music” is a really huge taxonomy, but what I like best right now from that continent is new African jazz, Congolese Soukous, and the completely simple yet amazingly workable rhythms of Noise Khanyile from South Africa.

I speak just enough Spanish to stay out of trouble in Tijuana, but my French (the official language of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo) is limited to winemaking terms and the chorus of a song by Patti LaBelle. I am completely lost in the IsiZulu sung by Noise Khanyile and his band members and in the song titles (“Kwazamazama Umkhomazi”?). My lack of international language skills notwithstanding, I can tell a love song from a rock-out song from a place song. I especially like “place” songs -- songs about a certain place.

Love songs, in whatever language, typically repeat a person’s name or symbolic trait. Rock-out songs are driven by the power of the instruments and have voice inflections that are more calls-to-arms than passive, sentimental terms of endearment. Place songs combine the styles and intents of love songs and rock-out songs. The musicians use their instruments to express their love for that singular place, and lyrics in these songs about towns, counties, or countries show love in persuasive terms. I have yet to hear a love song intoning the message “I love Linda, and so should you,” but I have heard many songs about Cuba extolling that very sentiment. Luis Conte sings about “Cuba linda” in a way that undoubtedly encourages foreigners to love her as he loves her. In fact, the prevalence of Cuban songs proclaiming the wonders of that fine country make me wonder if Fidel Castro imposes a “one song extolling the beauty of Cuba” clause for a

- I will now speak of the Missouri territory generally. […] The climate is generally salubrious and healthy, and the face of the country beautiful, salubrious and inviting. Lead and iron ore are in very great abundance; salt springs plenty. In short, nature has been truly bountiful in the distribution of her favours in this territory.

Salubrious means "that which promotes health or well-being."

Salubrious means "that which promotes health or well-being."

In the St. Charles [MO] Democrat, Father Münch offered his impression on this wild western state: "The state of Missouri apparently is the area in which the good red wine is produced." Father Münch wrote this nearly 50 years after Mr. Sibley’s letter, and Missouri had made major advances in winemaking in those 50 years. In that time, European emigrants (heeding Mr. Sibley’s sage advice?) came to this area by the wagonload. They settled along the Missouri River in St. Louis and further up the river in towns like Augusta and Hermann. They printed newspapers in German, established fine schools, planted grape vines, and made wine. Near the turn of the century, the Stone Hill Wine Company in Hermann was the second largest winery in the nation and the third largest in the world.

Stone Hill Winery today produces high quality wine, and the Adam Puchta Winery (also in Hermann) recently celebrated 150 years of uninterrupted family winemaking. Hermann’s Oak Glen Winery owns 5 or 6 rows of Norton vines originally planted in the 1850s. That very Norton could be the wine Father Münch wrote about, although it was called Virginia Seedling or Virginia Sämling in his time.

Hermann and Augusta are not the only winemaking areas in the state, however. In total, around 50 wineries exist in Missouri. Most are located within 30 miles of the Missouri River, but a dozen others dot the state, mainly south of the River. The boundaries of the huge Ozark Mountain Viticultural Area lasso over half of the state’s wineries, and the Augusta and Hermann sub-appellations corral about one-fourth of those.

From the Illinois and Iowa Deep Loess and Drift, to the Southern Mississippi Alluvium, to the Springfield Plain, to the Central Claypan Areas, soil and climate conditions of the Missouri state appellation vary greatly. Bedrock ages span from the Precambrian era (near Ste. Genevieve) to Tertiary and Quaternary eras (along the Missouri River). This translates alluvial soil in the river areas, loess and clay in the prairie areas, and rocky soils on the hills. The myriad microclimates, growing and vinifying practices, and cultivar selections produce a wide array of wine styles and quality. Missouri wines cannot be made anywhere but in Missouri.

Streets and highways throughout Missouri are generally in rough shape. Heaving in the frigid winters and kinking in the steamy summers create potholes and cracked asphalt. These extreme climactic conditions call for viticultural diligence and careful rootstock selection. Many vineyard workers set down their pruning shears on a Friday in late winter only to pick up the planting shovel on the next Monday in early spring.

It may be due to a Midwestern temperament or to a wide-open market, but secrecy and hostile competition are not found in Missouri wineries. The first thing you hear when you enter a winery in Missouri might be “I’m glad you found us.” Chances are that you, too, will be glad you found them. The agricultural abilities of many farmers-turned-vintners are evident in their clean fruit, and subsequently, in their pleasingly unexpected wines. As you turn onto a gravel drive leading to a Missouri winery, you might see a bunch (herd?... flock?) of alpacas or miniature horses roaming around the neighboring ranch. But Missouri is not all cows and sweet wine blends. You may well be surprised at the large-winery quality of the Chardonel at a small winery; just as you might be surprised at the boutique-winery taste of the Seyval Blanc at a large winery. Missouri has great Champagne, port, and sherry, too.

In my ongoing travels to taste wine in every winery in the state of Missouri, I do a lot of driving. Always about one decade behind the times, I play a lot of cassette tapes as I tootle down two lane blacktop roads to the next tasting room. I am completely crazy about Cuban, Puerto Rican, and African music. “African music” is a really huge taxonomy, but what I like best right now from that continent is new African jazz, Congolese Soukous, and the completely simple yet amazingly workable rhythms of Noise Khanyile from South Africa.

I speak just enough Spanish to stay out of trouble in Tijuana, but my French (the official language of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo) is limited to winemaking terms and the chorus of a song by Patti LaBelle. I am completely lost in the IsiZulu sung by Noise Khanyile and his band members and in the song titles (“Kwazamazama Umkhomazi”?). My lack of international language skills notwithstanding, I can tell a love song from a rock-out song from a place song. I especially like “place” songs -- songs about a certain place.

Love songs, in whatever language, typically repeat a person’s name or symbolic trait. Rock-out songs are driven by the power of the instruments and have voice inflections that are more calls-to-arms than passive, sentimental terms of endearment. Place songs combine the styles and intents of love songs and rock-out songs. The musicians use their instruments to express their love for that singular place, and lyrics in these songs about towns, counties, or countries show love in persuasive terms. I have yet to hear a love song intoning the message “I love Linda, and so should you,” but I have heard many songs about Cuba extolling that very sentiment. Luis Conte sings about “Cuba linda” in a way that undoubtedly encourages foreigners to love her as he loves her. In fact, the prevalence of Cuban songs proclaiming the wonders of that fine country make me wonder if Fidel Castro imposes a “one song extolling the beauty of Cuba” clause for a