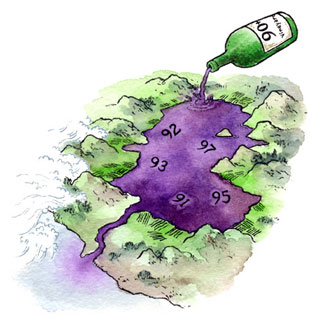

Is the quest for high scores obscuring the

regional identity of wine?

Lost in the Numbers

An old Terroirist’s commentary on Wine-by-Numbers and the loss of Regional Tipicity.

by

Dan Berger

December 24, 2005

It has been a couple of decades since we’ve been asked to take on faith the concept that a great wine is one that a self-proclaimed expert perceives it to be without any evidence whatever of the essential components of the wine being there.

The recent definition of a great wine has been based on concentration and weight and has nothing to do with the two most vital aspects of the characteristics of a truly great wine: varietal definition and regional typicity. We all know that it’s possible to make a dark, heavy wine by manipulation, but who ever said that that trait, in and of itself, was a prerequisite for a wine being great -- and the only significant criterion for making that claim?

One thing I learned when I first got into wine was that if you bought a Cabernet Sauvignon, it wasn’t a good wine if it didn’t smell and taste something like Cabernet Sauvignon. For it to be even successful and drinkable, let alone a classic, it had to smell and taste like the grape on the label. Soon after, I read about the importance of regional character, and although it wasn’t defined in quite as specific a way as was varietal character, the idea was simple: not only was a great wine true to its grape heritage, but it would show some sense of the place from which it came.

In fact, as I learned from talking with those who owned the greatest wineries, a truly great wine could not be simply more of the same thing; the great wines all had their own unique distinctiveness that came from their vineyards.

This “home-soil character” could be obvious or subtle, but without a trace of it, the wine was somehow lacking, they all said. I heard this directly from the master, California’s greatest wine maker, Andre Tchelistcheff, when he described the “Rutherford dust” element in his top Cabernets. I heard it from numerous French vintners who trekked to this country in the 1970s when I was forming the base of wine knowledge that eventually led to a career in this game.

Thus was terroir fixed in my mind as inextricably linked to great wine. Which has led, for me, to an axiom that ought to be in every wine lover’s mind’s eye: no wine can ever truly be described as great without some elements of both varietal intensity and terroir character.

We who believe in terroir take a lot on faith. Those who completely detest and dismiss the idea of terroir say it is blind faith to accept it as a fact. And thus you can see where the twain never shall agree. I call these people simplists because they seem to revel in the utter uniformity of all wines they deem to be great.

We realize that the concept of terroir itself is not easy to grasp: that the grape varietal has an equal and vitally important companion, which is the essence of what the region brings to it. That equalizer is the soil, the very plot of ground where the wine grapes grow, along with the air in which it thrives and the weather patterns that typically affect that air. Terroir even plays a role in bizarre vintages, such as 2003 in Europe when a massive heat wave plagued the continent. It is this theory of terroir that says that the soil and weather have as much of an influence as does the variety of grape.

What makes this concept so hard to grasp is that there is no direct parallel in other fruits and vegetables. An Early Girl tomato grown in Bakersfield smells and tastes pretty much the same as the same variety of tomato grown in Ukiah, even if one is grown hydroponically and the other is grown in soil. Or does it? One key point here is that no one ever stages a blind tasting of Early Girl tomatoes from different regions or growing conditions. If someone did actually stage a tasting of Early Girl tomatoes from different growing regions, would there be a significant difference in how they smelled and tasted? Or would the differences be trivial? Or would there be no essential difference at all?

But we do, seemingly, stage all sorts of blind tastings of just about every wine on the planet. That’s how we can know that a Musigny is more like another Musigny than it is like a Corton. On the other hand, with some reviewers, the “best” Musigny is one that is weighty. A more elegant version would be marked down, and a more weighty Corton would be marked up. So much for terroir.

As for the tomato analogy, it may be that the soil does impart a special character to all sorts of other plants, and we simply haven’t seen it at this point. How many professional tomato tasters are there? (And, more to the point, does it matter? Even if there were a significant difference between two tomatoes of the same variety growing in differing regions, would one be worth intrinsically more than the other? Tomatoes are a commodity, and the market sets a price based on the volume of tomatoes available, not generally on quality and certainly not on regionality.)

(The only area of vegetables I am aware of in which this seems to be an issue is with onions. Walla Walla, Maui, or Vidalia onions are three regionally prominent kinds of onions that are sweeter than others.)

Back to wine: if terroir does exist, as so many people say it does, then it is obvious that it competes with varietal character for the dominant feature in a wine’s basic sensory elements. If this is so, which is more important, the regional or the varietal? This is a lot knottier of a question for philosophers than it is for wine purists.

Clearly, the French, notably in regions like Bordeaux and Burgundy, believe that terroir is an essential element in the makeup of a wine, else they would not rely so heavily on naming wines for regions rather than varietals. A high-caliber Bordeaux can be mostly Merlot (Petrus), mostly Cabernet Sauvignon (Mouton), or a mix in which no variety tops 50% (Pichon Lalande).

However, there appears to be a huge paradox here: if the French so firmly believed in the power of terroir to imprint on the wines of each of the prestigious growing regions, why on earth did they restrict the grapes that may be grown in them? They didn’t, after all, limit the grapes of “lesser” regions such as Provence.

If the concept of terroir existed before the quest to limit the grapes for quality reasons, and the French knew instinctively that terroir was more important than varietal character, then the burgers of Bordeaux would have had no need to limit the grapes grown there to those that today are mandated. Pinot Noir would have been permitted, I believe, because to restrict it would have been to buy into the notion that terroir was really only a myth, and to uphold the notion of regional character, the grapes had to be limited to those that produced a certain anticipated character.

To use a more extreme example, if terroir were so compelling an idea, why did the French need to restrict the grape varieties of Montrachet to Chardonnay? They could very well have argued, “Terroir defines a character in every wine that emanates from a particular soil and growing region, so it matters little which grapes grow here. So we will permit any grape to grow here, because the character of the resulting wine will reflect the soil at least as much as the varietal does.” And thus they could well have permitted Riesling to grow in Montrachet, with their faith in terroir giving them the confidence that the resulting wine would be reflective more of Montrachet,

The recent definition of a great wine has been based on concentration and weight and has nothing to do with the two most vital aspects of the characteristics of a truly great wine: varietal definition and regional typicity. We all know that it’s possible to make a dark, heavy wine by manipulation, but who ever said that that trait, in and of itself, was a prerequisite for a wine being great -- and the only significant criterion for making that claim?

One thing I learned when I first got into wine was that if you bought a Cabernet Sauvignon, it wasn’t a good wine if it didn’t smell and taste something like Cabernet Sauvignon. For it to be even successful and drinkable, let alone a classic, it had to smell and taste like the grape on the label. Soon after, I read about the importance of regional character, and although it wasn’t defined in quite as specific a way as was varietal character, the idea was simple: not only was a great wine true to its grape heritage, but it would show some sense of the place from which it came.

In fact, as I learned from talking with those who owned the greatest wineries, a truly great wine could not be simply more of the same thing; the great wines all had their own unique distinctiveness that came from their vineyards.

This “home-soil character” could be obvious or subtle, but without a trace of it, the wine was somehow lacking, they all said. I heard this directly from the master, California’s greatest wine maker, Andre Tchelistcheff, when he described the “Rutherford dust” element in his top Cabernets. I heard it from numerous French vintners who trekked to this country in the 1970s when I was forming the base of wine knowledge that eventually led to a career in this game.

Thus was terroir fixed in my mind as inextricably linked to great wine. Which has led, for me, to an axiom that ought to be in every wine lover’s mind’s eye: no wine can ever truly be described as great without some elements of both varietal intensity and terroir character.

We who believe in terroir take a lot on faith. Those who completely detest and dismiss the idea of terroir say it is blind faith to accept it as a fact. And thus you can see where the twain never shall agree. I call these people simplists because they seem to revel in the utter uniformity of all wines they deem to be great.

We realize that the concept of terroir itself is not easy to grasp: that the grape varietal has an equal and vitally important companion, which is the essence of what the region brings to it. That equalizer is the soil, the very plot of ground where the wine grapes grow, along with the air in which it thrives and the weather patterns that typically affect that air. Terroir even plays a role in bizarre vintages, such as 2003 in Europe when a massive heat wave plagued the continent. It is this theory of terroir that says that the soil and weather have as much of an influence as does the variety of grape.

What makes this concept so hard to grasp is that there is no direct parallel in other fruits and vegetables. An Early Girl tomato grown in Bakersfield smells and tastes pretty much the same as the same variety of tomato grown in Ukiah, even if one is grown hydroponically and the other is grown in soil. Or does it? One key point here is that no one ever stages a blind tasting of Early Girl tomatoes from different regions or growing conditions. If someone did actually stage a tasting of Early Girl tomatoes from different growing regions, would there be a significant difference in how they smelled and tasted? Or would the differences be trivial? Or would there be no essential difference at all?

But we do, seemingly, stage all sorts of blind tastings of just about every wine on the planet. That’s how we can know that a Musigny is more like another Musigny than it is like a Corton. On the other hand, with some reviewers, the “best” Musigny is one that is weighty. A more elegant version would be marked down, and a more weighty Corton would be marked up. So much for terroir.

As for the tomato analogy, it may be that the soil does impart a special character to all sorts of other plants, and we simply haven’t seen it at this point. How many professional tomato tasters are there? (And, more to the point, does it matter? Even if there were a significant difference between two tomatoes of the same variety growing in differing regions, would one be worth intrinsically more than the other? Tomatoes are a commodity, and the market sets a price based on the volume of tomatoes available, not generally on quality and certainly not on regionality.)

(The only area of vegetables I am aware of in which this seems to be an issue is with onions. Walla Walla, Maui, or Vidalia onions are three regionally prominent kinds of onions that are sweeter than others.)

Back to wine: if terroir does exist, as so many people say it does, then it is obvious that it competes with varietal character for the dominant feature in a wine’s basic sensory elements. If this is so, which is more important, the regional or the varietal? This is a lot knottier of a question for philosophers than it is for wine purists.

Clearly, the French, notably in regions like Bordeaux and Burgundy, believe that terroir is an essential element in the makeup of a wine, else they would not rely so heavily on naming wines for regions rather than varietals. A high-caliber Bordeaux can be mostly Merlot (Petrus), mostly Cabernet Sauvignon (Mouton), or a mix in which no variety tops 50% (Pichon Lalande).

However, there appears to be a huge paradox here: if the French so firmly believed in the power of terroir to imprint on the wines of each of the prestigious growing regions, why on earth did they restrict the grapes that may be grown in them? They didn’t, after all, limit the grapes of “lesser” regions such as Provence.

If the concept of terroir existed before the quest to limit the grapes for quality reasons, and the French knew instinctively that terroir was more important than varietal character, then the burgers of Bordeaux would have had no need to limit the grapes grown there to those that today are mandated. Pinot Noir would have been permitted, I believe, because to restrict it would have been to buy into the notion that terroir was really only a myth, and to uphold the notion of regional character, the grapes had to be limited to those that produced a certain anticipated character.

To use a more extreme example, if terroir were so compelling an idea, why did the French need to restrict the grape varieties of Montrachet to Chardonnay? They could very well have argued, “Terroir defines a character in every wine that emanates from a particular soil and growing region, so it matters little which grapes grow here. So we will permit any grape to grow here, because the character of the resulting wine will reflect the soil at least as much as the varietal does.” And thus they could well have permitted Riesling to grow in Montrachet, with their faith in terroir giving them the confidence that the resulting wine would be reflective more of Montrachet,