Diamond Mountain District ~ Napa Valley (AVA)

At home on Diamond Mountain

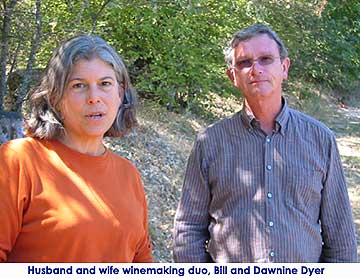

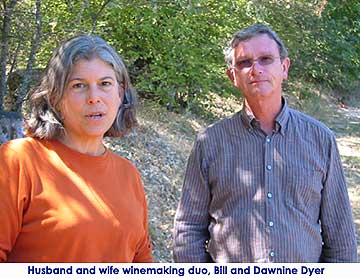

The Diamond Mountain District provides an ideal terroir for Cabernet Sauvignon, but for veteran winemakers Bill and Dawnine Dyer, it also provides safe refuge from the corporate life.

by

Alan Goldfarb

September 19, 2005

Bill Dyer says he came home to Calistoga one day in the midst of the harvest of 1991, which he calls “the crush from hell” at Sterling -- where he was the winemaker for 20 years -- sat down to pour himself a beer, and listened to his neighbors arguing. He had another brew and then turned to his wife Dawnine and exclaimed, “Let’s get out of here. Let’s move to the country.”

It would be another five years for Bill at Sterling, and another nine for Dawnine at Domaine Chandon, where she was the winemaker for 24 years, before the Dyers finally “got out of here.”

Getting out meant extricating themselves from the corporate world, finding a piece of property of their own, and making wine for themselves.

Now, firmly ensconced on an 11-acre parcel on Diamond Mountain, the Dyers make about 400 cases a year of Cabernet Sauvignon for their Dyer Vineyard brand, that comes off a sweet little 2½-acre plot that sits across from Diamond Creek Vineyards; and which is priced at $70.

There are no plans to make much more wine. Nor is there any motivation whatsoever to go back to the corporate life for this quiet, unassuming, and talented couple who have been together since they met at UC Santa Cruz almost 30 years ago.

“I got tired of meetings and tired of working on a five-year plan,” Bill Dyer says sardonically from a little courtyard amidst their Mediterranean-style rammed-earth home. “I got tired of missions, that I called ‘mission-positions,’ and they didn’t seem to like that.”

By “they,” Dyer was referring to the corporate suits who owned Sterling at the time. Which was just fine with Dyer.

“When I left, I didn’t want to work for another corporation,” he explains. “I wanted to be self-employed.”

After almost a quarter-century helping to put a French sparkling wine house on the California map at Chandon, Dawnine had had it, too.

“I left primarily because this project (meaning Dyer Vineyard) was growing and Chandon was changing,” she says. “It was a calculated risk; and I was watching Bill taking control of his life.”

Dawnine realized that “we were over-employed,” while Bill figured that at Sterling and Chandon, “we were making 11 percent of all the wine in the Napa Valley… and we were working too hard.”

While Dawnine interjects, “Oh, I don’t know about that. We were young back then,” both agree that jumping off the corporate culture wagon was the absolute right thing to do.

Now in their mid-50s (Bill is 56, Dawnine is a year younger), and with Dyer Vineyards garnering much respect, the choice seems to be a sound one.

The wines are made at von Strasser just down the road. Rudy von Strasser’s crew does the harvesting of the Dyer vineyard that is set into a natural bowl that when Dawnine and Bill ever decide to get out of the wine business, one can visualize the vines being replaced by a lovely little country ball field.

In the meanwhile the vines, first planted in ’93, still hold the Dyer’s rapt attention. They earn extra revenue by consulting for Sodaro in Coombsville, while Bill does some work for Marimar Torres in Sonoma County, and for the Church & State Winery on Vancouver Island. (He’s no longer consulting for Burrowing Owl in the Okanagan Valley of British Columbia.)

Working for themselves is where the Dyers are most comfortable.

“It’s an absolute pleasure,” says Dawnine about working on their own label. “It seems like something you can do well. We think we can do this for a long time.”

“I had a great time at Domaine Chandon. It was an incredible opportunity… but at some point, you realize a ship is pretty big and you’re not going to do that forever.”

Dawnine concludes her colloquy on the corporate life, “We saw a lot of growth, we saw a lot of vineyards, we saw a lot of fruit -- and we saw the future.”

The future obviously, is now. There are plans to make a second brand of about 500 cases, produced from grapes from Coombsville and Spring Mountain, which will sell in the $40-$50 range and will be released next spring.

“We’re wanting to see if there’s a critical size that will make a good business model,” Dawnine says in answer to a question regarding growth. “We don’t want to spend all of our time and energy building a facility and selling wine.”

But she leaves open the possibility of expanding by saying with a laugh, “We’ll tell you in a few years.”

It would be another five years for Bill at Sterling, and another nine for Dawnine at Domaine Chandon, where she was the winemaker for 24 years, before the Dyers finally “got out of here.”

Getting out meant extricating themselves from the corporate world, finding a piece of property of their own, and making wine for themselves.

Now, firmly ensconced on an 11-acre parcel on Diamond Mountain, the Dyers make about 400 cases a year of Cabernet Sauvignon for their Dyer Vineyard brand, that comes off a sweet little 2½-acre plot that sits across from Diamond Creek Vineyards; and which is priced at $70.

There are no plans to make much more wine. Nor is there any motivation whatsoever to go back to the corporate life for this quiet, unassuming, and talented couple who have been together since they met at UC Santa Cruz almost 30 years ago.

“I got tired of meetings and tired of working on a five-year plan,” Bill Dyer says sardonically from a little courtyard amidst their Mediterranean-style rammed-earth home. “I got tired of missions, that I called ‘mission-positions,’ and they didn’t seem to like that.”

By “they,” Dyer was referring to the corporate suits who owned Sterling at the time. Which was just fine with Dyer.

“When I left, I didn’t want to work for another corporation,” he explains. “I wanted to be self-employed.”

After almost a quarter-century helping to put a French sparkling wine house on the California map at Chandon, Dawnine had had it, too.

“I left primarily because this project (meaning Dyer Vineyard) was growing and Chandon was changing,” she says. “It was a calculated risk; and I was watching Bill taking control of his life.”

Dawnine realized that “we were over-employed,” while Bill figured that at Sterling and Chandon, “we were making 11 percent of all the wine in the Napa Valley… and we were working too hard.”

While Dawnine interjects, “Oh, I don’t know about that. We were young back then,” both agree that jumping off the corporate culture wagon was the absolute right thing to do.

Now in their mid-50s (Bill is 56, Dawnine is a year younger), and with Dyer Vineyards garnering much respect, the choice seems to be a sound one.

The wines are made at von Strasser just down the road. Rudy von Strasser’s crew does the harvesting of the Dyer vineyard that is set into a natural bowl that when Dawnine and Bill ever decide to get out of the wine business, one can visualize the vines being replaced by a lovely little country ball field.

In the meanwhile the vines, first planted in ’93, still hold the Dyer’s rapt attention. They earn extra revenue by consulting for Sodaro in Coombsville, while Bill does some work for Marimar Torres in Sonoma County, and for the Church & State Winery on Vancouver Island. (He’s no longer consulting for Burrowing Owl in the Okanagan Valley of British Columbia.)

Working for themselves is where the Dyers are most comfortable.

“It’s an absolute pleasure,” says Dawnine about working on their own label. “It seems like something you can do well. We think we can do this for a long time.”

“I had a great time at Domaine Chandon. It was an incredible opportunity… but at some point, you realize a ship is pretty big and you’re not going to do that forever.”

Dawnine concludes her colloquy on the corporate life, “We saw a lot of growth, we saw a lot of vineyards, we saw a lot of fruit -- and we saw the future.”

The future obviously, is now. There are plans to make a second brand of about 500 cases, produced from grapes from Coombsville and Spring Mountain, which will sell in the $40-$50 range and will be released next spring.

“We’re wanting to see if there’s a critical size that will make a good business model,” Dawnine says in answer to a question regarding growth. “We don’t want to spend all of our time and energy building a facility and selling wine.”

But she leaves open the possibility of expanding by saying with a laugh, “We’ll tell you in a few years.”