Even on stormy days the view from Cain on Spring Mountain gives believers a glimpse of real terroir, in the most religious sense.

Spring Mountain District ~ Napa Valley (AVA)

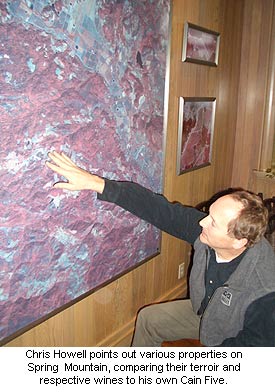

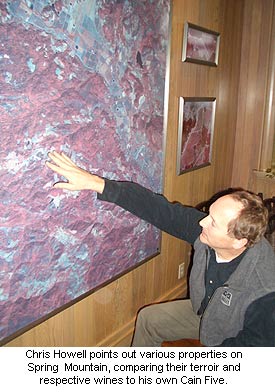

Cain Vineyard’s Chris Howell Puzzles over Terroir

Winemaker Chris Howell knows that honoring the terroir of sacred places can be an almost religious pursuit that doesn’t always make sense commercially.

by

Alan Goldfarb

May 9, 2006

Chris Howell puzzles about terroir, which shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone who’s known him as long as I have. The fact is Howell, as soft-spoken and contemplative as most anyone in the California wine industry, puzzles over most things. Which to my mind, due to his considerably filled brain pan, is a good thing.

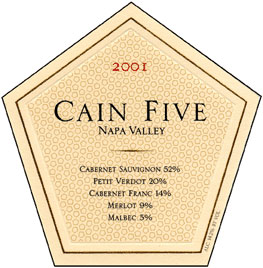

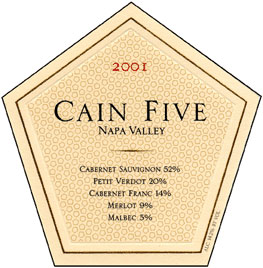

Howell is the longtime winemaker and general manager at Cain Vineyard & Winery which sits on a southeastern spur on top of Spring Mountain and above the central Napa Valley town of St. Helena. It’s here, on Langtry Road about 2,000 feet above the valley floor, that his most notable wine – the estate-made Cain Five – utilizes all five Bordeaux red varieties in its assemblage. He also makes two other red blends, much of the fruit for which comes from the valley below.

On a recent afternoon, while a fierce rainstorm added several inches to the more than eight feet of water that belted the mountain this season, Howell almost poetically relates the considerable amount of thought he’s given to the idea of terroir.

Sitting in the winery’s Gothic-like great room as rain pelts the tall mullioned windows as if ensnared in a carwash, Howell thinks that the very notion of terroir “is a religion.” But on the other hand, he also knows that terroir “is a business and marketing,” but not necessarily “in a bad sense.”

“Religion comes with a site such as Chambertin (the Burgundian grand cru vineyard in the Côte d’Or). It is sacred,” he says. “People (there) know they have something precious and they’d better not screw it up.”

The “people” to whom Howell refers are the winemakers. In France, where vignerons are far less important than the almost iconic of stations to which we’ve assigned the North American winemaker, terroir is a more palpable expression of a wine. Here in America, Howell thinks, the “winemaker trumps terroir.”

“Terroir is a human thing (here). It’s not a natural thing to where there wouldn’t ever be a Chambertin. When you go to prune your vines in Chambertin, it is like going to temple. You have the elders sing this song and one day, they make you (sing it too).

“One day, if we have a generous friend who pops a cork on that (Chambertin), that’s religion.”

Howell continues his diatribe almost in a whisper, “Who are we? We lowly, commercial types – I’m thinking Tolkien and The Golem; ‘Can we have some of that terroir?’

“Are we worthy and will it take us a thousand years?”

He says, “For Burgundians, terroir is super-real. Most of us know it’s all about the grapes. That’s the truth that goes beyond us. For us (believers), terroir is the truth. (But) some winemakers think it’s all about them. But how do you get at (terroir) wines from different sites, made in the same cellar by the same hands? … The hands of the people making the wine, has a lot to do with the taste of the wine.”

But in the end, in North America at the beginning of the 21st century, Howell believes terroir “is a business … It’s an aid, a path to explain all these different wines and the market establishes what is special and what is not. It’s also fashion, a fad.”

He sites Spottswoode’s and Viader’s wines as displaying their terroir. “I have a feeling what they taste like,” he says, and then mentions his neighbor a mile down the mountain, York Creek Vineyards from which he buys fruit.

“I’m surprised when I visit Fritz Maytag (York Creek’s owner and the scion to the Maytag washing machine company and of Maytag blue cheese). The flavors (of the York Creek wines) are similar to Cain … It’s visceral. You’re not expecting it to taste like this, but there it is.”

At Cain, he explains, the soils are comprised of shallow clay and yield low tonnage (1 to 2 tons per acre). The earth there is high in magnesium and potassium. But while the soils at York Creek are deeper, the wines which originate from his 40 acres and from Maytag’s parcel both tend to be on the “difficult side.” That’s because Spring Mountain is a cool region. Its weather comes from the ocean about 40 miles to the west and it’s far cooler, above the fog line, and wetter than the vineyards on the valley floor.

It all adds up to giving the Cain Five its aromatics. The tannins are green and intense but somehow the wine tends to display a great deal of finesse.

Howell calls his vineyard “an outlier,” but he says, his wines tend to have a lot in common with neighboring Marston, Newton, and the aforementioned York Creek.

But when it all shakes out, he contends that achieving “terroir in the Napa Valley will take a thoughtful approach. … The Burgundians say not all places have terroir.”

Perhaps that is the case on the valley floor.

“Wines get more generic down in the valley because the soils are siltier. You can find the spots, but as you get closer to the (Napa) river, you get more generic.

“(But) just because you’re in the hills, how do you know that what you have is special?” he asks. And, concludes in his inimitable way, “And how would you know it?”

So then, will North American consumers ever get to understand and taste terroir in their glass?

“Today we have scientific conferences to talk about terroir. We may or may not be looking for these sacred places and we may not be working with the precision that the Burgundians work with,” he explains. “At Cain, it isn’t as much about the varieties as it is about the site. …we end up with a signature so that we can come up with a sense of terroir that is functionary.

“This is what I’m puzzling with. (Cain Five) isn’t the easiest wine to drink. I’m puzzling with the fact that the most successful wines we’ve had are the wines that come from down in the valley. But the most intense wines are those that came from within this vineyard,” he says, pointing out the windows that have rainwater cascading in sheets down their glass.

“The paradox is, it would be commercially easier to put the two (wines) together. But if you’re a Burgundian, you’ve just killed it (the terroir). This property may be more difficult, but I absolutely believe in it.”

~ Alan Goldfarb, Napa Valley Editor

To comment on Alan Goldfarb’s writings and thoughts, contact him at a.goldfarb@appellationamerica.com

Howell is the longtime winemaker and general manager at Cain Vineyard & Winery which sits on a southeastern spur on top of Spring Mountain and above the central Napa Valley town of St. Helena. It’s here, on Langtry Road about 2,000 feet above the valley floor, that his most notable wine – the estate-made Cain Five – utilizes all five Bordeaux red varieties in its assemblage. He also makes two other red blends, much of the fruit for which comes from the valley below.

On a recent afternoon, while a fierce rainstorm added several inches to the more than eight feet of water that belted the mountain this season, Howell almost poetically relates the considerable amount of thought he’s given to the idea of terroir.

Sitting in the winery’s Gothic-like great room as rain pelts the tall mullioned windows as if ensnared in a carwash, Howell thinks that the very notion of terroir “is a religion.” But on the other hand, he also knows that terroir “is a business and marketing,” but not necessarily “in a bad sense.”

“Religion comes with a site such as Chambertin (the Burgundian grand cru vineyard in the Côte d’Or). It is sacred,” he says. “People (there) know they have something precious and they’d better not screw it up.”

The “people” to whom Howell refers are the winemakers. In France, where vignerons are far less important than the almost iconic of stations to which we’ve assigned the North American winemaker, terroir is a more palpable expression of a wine. Here in America, Howell thinks, the “winemaker trumps terroir.”

“Terroir is a human thing (here). It’s not a natural thing to where there wouldn’t ever be a Chambertin. When you go to prune your vines in Chambertin, it is like going to temple. You have the elders sing this song and one day, they make you (sing it too).

“One day, if we have a generous friend who pops a cork on that (Chambertin), that’s religion.”

Howell continues his diatribe almost in a whisper, “Who are we? We lowly, commercial types – I’m thinking Tolkien and The Golem; ‘Can we have some of that terroir?’

“Are we worthy and will it take us a thousand years?”

He says, “For Burgundians, terroir is super-real. Most of us know it’s all about the grapes. That’s the truth that goes beyond us. For us (believers), terroir is the truth. (But) some winemakers think it’s all about them. But how do you get at (terroir) wines from different sites, made in the same cellar by the same hands? … The hands of the people making the wine, has a lot to do with the taste of the wine.”

But in the end, in North America at the beginning of the 21st century, Howell believes terroir “is a business … It’s an aid, a path to explain all these different wines and the market establishes what is special and what is not. It’s also fashion, a fad.”

He sites Spottswoode’s and Viader’s wines as displaying their terroir. “I have a feeling what they taste like,” he says, and then mentions his neighbor a mile down the mountain, York Creek Vineyards from which he buys fruit.

“I’m surprised when I visit Fritz Maytag (York Creek’s owner and the scion to the Maytag washing machine company and of Maytag blue cheese). The flavors (of the York Creek wines) are similar to Cain … It’s visceral. You’re not expecting it to taste like this, but there it is.”

At Cain, he explains, the soils are comprised of shallow clay and yield low tonnage (1 to 2 tons per acre). The earth there is high in magnesium and potassium. But while the soils at York Creek are deeper, the wines which originate from his 40 acres and from Maytag’s parcel both tend to be on the “difficult side.” That’s because Spring Mountain is a cool region. Its weather comes from the ocean about 40 miles to the west and it’s far cooler, above the fog line, and wetter than the vineyards on the valley floor.

It all adds up to giving the Cain Five its aromatics. The tannins are green and intense but somehow the wine tends to display a great deal of finesse.

Howell calls his vineyard “an outlier,” but he says, his wines tend to have a lot in common with neighboring Marston, Newton, and the aforementioned York Creek.

But when it all shakes out, he contends that achieving “terroir in the Napa Valley will take a thoughtful approach. … The Burgundians say not all places have terroir.”

Perhaps that is the case on the valley floor.

“Wines get more generic down in the valley because the soils are siltier. You can find the spots, but as you get closer to the (Napa) river, you get more generic.

“(But) just because you’re in the hills, how do you know that what you have is special?” he asks. And, concludes in his inimitable way, “And how would you know it?”

So then, will North American consumers ever get to understand and taste terroir in their glass?

“Today we have scientific conferences to talk about terroir. We may or may not be looking for these sacred places and we may not be working with the precision that the Burgundians work with,” he explains. “At Cain, it isn’t as much about the varieties as it is about the site. …we end up with a signature so that we can come up with a sense of terroir that is functionary.

“This is what I’m puzzling with. (Cain Five) isn’t the easiest wine to drink. I’m puzzling with the fact that the most successful wines we’ve had are the wines that come from down in the valley. But the most intense wines are those that came from within this vineyard,” he says, pointing out the windows that have rainwater cascading in sheets down their glass.

“The paradox is, it would be commercially easier to put the two (wines) together. But if you’re a Burgundian, you’ve just killed it (the terroir). This property may be more difficult, but I absolutely believe in it.”

~ Alan Goldfarb, Napa Valley Editor

To comment on Alan Goldfarb’s writings and thoughts, contact him at a.goldfarb@appellationamerica.com