Limestone does exist in the Westside of Paso Robles but it can sometimes take a little research to find it.

Paso Robles: An American Terroir -- An interview with Dr. Thomas J. Rice

"Limestone does exist throughout Paso Robles, but not in huge formations like boulders or cliffs, as in parts of France."

by

Mary Baker

November 7, 2006

Mary Baker (MB): Dr. Rice, how is your book organized?

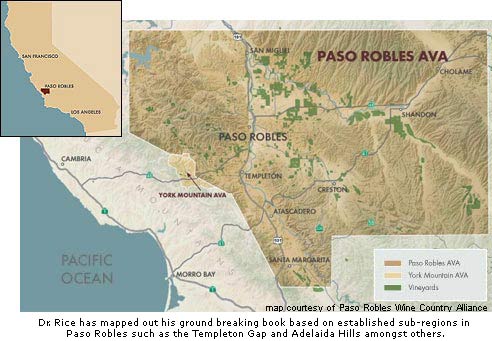

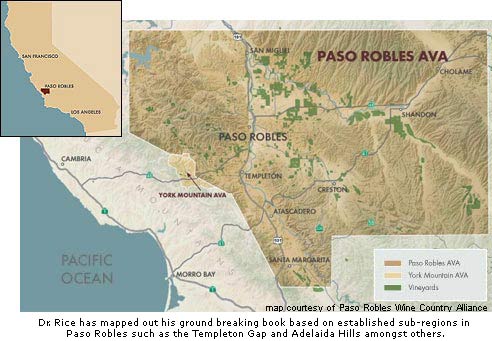

Thomas Rice (TR): An introduction describes the terroir as seen through the eyes of early ranching, farming and winegrowing families. Chapter One discusses environmental contrasts between the east side and west side, and general issues of water quality, wildlife habitat and native plants.

The remaining chapters are organized by region: Templeton Gap, Adelaida Hills, Salinas River Valley Terraces West, Estrella River Terraces, Salinas River Terraces Southeast, and the Creston/Shandon Area. Terraces West would include the San Marcos drainage area, and the Dusi Ranch vineyards. The Southeast Terraces are possibly two separate regions -- Santa Margarita and Huerhuero River Terraces. Although there are not many wineries in that region, there are big vineyards, with abundant geologic and soil variability. This region encompasses vineyards as diverse as Wild Horse, Maloy O’Neill, and Chateau Margene.

There were redwood forests here during the Pleistocene (Ice Age), and huge flood plains which incised the land and were later uplifted into river terraces. There’s been a lot of folding and faulting of the land, causing deeper sedimentary rock layers to be forced underneath the plains. So, for instance, in the high plateaus and orchards of the El Pomar region, the eroded tops of the highest points may be calcareous shale and mudstone, with surrounding recent alluvium and a veneer of Paso Robles Formation (Pleistocene Ice Ages) alluvium consisting of mixed sand, gravel, and clay covering the sedimentary rock layers.

MB: How long have you been working on this book? What was the basis of your research?

TR: I’ve been working on this book for over twelve years. Tracy has spent four years on it. She is handling the cultural history aspect of the book, and is doing a fantastic job interviewing local vintners and viticulturists. We hope it will be a book that anyone interested in the region or in winemaking will find interesting. I have been “digging holes” throughout Paso Robles for over twenty years, and the book includes research from my own projects and also students’ projects which I have supervised.

TR: I’ve been working on this book for over twelve years. Tracy has spent four years on it. She is handling the cultural history aspect of the book, and is doing a fantastic job interviewing local vintners and viticulturists. We hope it will be a book that anyone interested in the region or in winemaking will find interesting. I have been “digging holes” throughout Paso Robles for over twenty years, and the book includes research from my own projects and also students’ projects which I have supervised.

MB: Would you describe the broad geological differences between the central coast and northern California? You mentioned previously that the San Andreas Fault curves off into the Pacific west of Napa, resulting in more volcanic rock in Napa, whereas Paso Robles is almost entirely sea floor. Are there other differences between north and south California?

TR: There are many geological differences between the two areas. Napa is part of the North American (NA) plate, which is an expansion zone in Napa Valley, moving slowly northward. It features volcanic rock, gravel alluvium, and shale layers. The coastal splinter of western California from the San Francisco Bay to Baja is a compression zone. It is being forced against the NA plate and is moving slowly northward along the San Andreas Fault, grinding against the plate like cheese against a grater.

San Andreas is more than just an inconvenient fault. The surface terrain of western California is shaped by folding and faulting, but much of the shoreline is created as various layers of the Pacific Plate slide under the North American Plate in a process called subduction. As these tectonic plates are pushed under the continent, shavings of ancient ocean crust containing coral and marine layers curl upward, creating new California coastline, and simultaneously pushing against it. This process is referred to as the San Andreas system, and it’s responsible for the parallel cracks and faults in much of western coastal California.

The Pacific Plate is comprised of ancient seabeds and shallow coral beds over oceanic volcanic crust. After being pushed up against the NA plate, shallow seabeds form again and recent sea floor materials are deposited on top of older seabeds, resulting in the rich marine layers and fossils which we find in the Monterey Formation rocks located around Paso Robles.

The Central Coast region was once like a huge Puget Sound, with embayments of shallow ocean life living in large marine estuarine systems, later to be deformed by the grinding pressures from different directions (north, south, up, down), due to movement along the San Andreas Fault. These Monterey Formation rocks were populated with ancestral marine sealife (fishes, corals, plankton) and ocean mammals like seals and whales.

MB: How would you compare Paso to other wine geo-regions throughout the world?

TR: There are geologic formations (ancient marine embayments) similar to those in Paso Robles throughout France and Italy -- in Tuscany, the Rhone and Bordeaux regions, even Burgundy. Also the southern Adelaida region of Australia has many limestone rock deposits. They are all mainly marine sediments that have weathered into soils over many thousands of years.

MB: In that case, are there differences between central coast and northern California soils?

TR: In terms of soils, all of the California winegrowing regions have a variety of soils, ranging from recent alluvial river deposits and eroded sedimentary layers, to ancient calcareous and siliceous (silica-rich) seabed deposits. But Paso Robles has a thicker deposit of Monterey (Miocene and Pliocene age) and Paso Robles Formations (Pleistocene), which feature calcium carbonate-rich (limestone, calcareous shale and mudstone) and silicate-rich (shales and sandstone) rocks. Sonoma County is on a small wedge of the Pacific Plate, but it contains more of the igneous, granitic and quartz-rich rocks characteristic of the western NA plate; and Napa has more volcanic rocks, such as diabase and basalt.

Napa soils receive more annual moisture, resulting in more weathered, acid soils with higher organic matter. They have low to non-existent calcium carbonate, and typical soil pH’s of 5.0 to 7.0.

Paso Robles is drier and the soils are less highly weathered, covered by less native biomass, and generally have lower organic matter levels. They’re more alkaline, with higher soil pH’s ranging from 6.0 t

Thomas Rice (TR): An introduction describes the terroir as seen through the eyes of early ranching, farming and winegrowing families. Chapter One discusses environmental contrasts between the east side and west side, and general issues of water quality, wildlife habitat and native plants.

The remaining chapters are organized by region: Templeton Gap, Adelaida Hills, Salinas River Valley Terraces West, Estrella River Terraces, Salinas River Terraces Southeast, and the Creston/Shandon Area. Terraces West would include the San Marcos drainage area, and the Dusi Ranch vineyards. The Southeast Terraces are possibly two separate regions -- Santa Margarita and Huerhuero River Terraces. Although there are not many wineries in that region, there are big vineyards, with abundant geologic and soil variability. This region encompasses vineyards as diverse as Wild Horse, Maloy O’Neill, and Chateau Margene.

There were redwood forests here during the Pleistocene (Ice Age), and huge flood plains which incised the land and were later uplifted into river terraces. There’s been a lot of folding and faulting of the land, causing deeper sedimentary rock layers to be forced underneath the plains. So, for instance, in the high plateaus and orchards of the El Pomar region, the eroded tops of the highest points may be calcareous shale and mudstone, with surrounding recent alluvium and a veneer of Paso Robles Formation (Pleistocene Ice Ages) alluvium consisting of mixed sand, gravel, and clay covering the sedimentary rock layers.

MB: How long have you been working on this book? What was the basis of your research?

TR: I’ve been working on this book for over twelve years. Tracy has spent four years on it. She is handling the cultural history aspect of the book, and is doing a fantastic job interviewing local vintners and viticulturists. We hope it will be a book that anyone interested in the region or in winemaking will find interesting. I have been “digging holes” throughout Paso Robles for over twenty years, and the book includes research from my own projects and also students’ projects which I have supervised.

TR: I’ve been working on this book for over twelve years. Tracy has spent four years on it. She is handling the cultural history aspect of the book, and is doing a fantastic job interviewing local vintners and viticulturists. We hope it will be a book that anyone interested in the region or in winemaking will find interesting. I have been “digging holes” throughout Paso Robles for over twenty years, and the book includes research from my own projects and also students’ projects which I have supervised.MB: Would you describe the broad geological differences between the central coast and northern California? You mentioned previously that the San Andreas Fault curves off into the Pacific west of Napa, resulting in more volcanic rock in Napa, whereas Paso Robles is almost entirely sea floor. Are there other differences between north and south California?

TR: There are many geological differences between the two areas. Napa is part of the North American (NA) plate, which is an expansion zone in Napa Valley, moving slowly northward. It features volcanic rock, gravel alluvium, and shale layers. The coastal splinter of western California from the San Francisco Bay to Baja is a compression zone. It is being forced against the NA plate and is moving slowly northward along the San Andreas Fault, grinding against the plate like cheese against a grater.

San Andreas is more than just an inconvenient fault. The surface terrain of western California is shaped by folding and faulting, but much of the shoreline is created as various layers of the Pacific Plate slide under the North American Plate in a process called subduction. As these tectonic plates are pushed under the continent, shavings of ancient ocean crust containing coral and marine layers curl upward, creating new California coastline, and simultaneously pushing against it. This process is referred to as the San Andreas system, and it’s responsible for the parallel cracks and faults in much of western coastal California.

The Pacific Plate is comprised of ancient seabeds and shallow coral beds over oceanic volcanic crust. After being pushed up against the NA plate, shallow seabeds form again and recent sea floor materials are deposited on top of older seabeds, resulting in the rich marine layers and fossils which we find in the Monterey Formation rocks located around Paso Robles.

The Central Coast region was once like a huge Puget Sound, with embayments of shallow ocean life living in large marine estuarine systems, later to be deformed by the grinding pressures from different directions (north, south, up, down), due to movement along the San Andreas Fault. These Monterey Formation rocks were populated with ancestral marine sealife (fishes, corals, plankton) and ocean mammals like seals and whales.

MB: How would you compare Paso to other wine geo-regions throughout the world?

TR: There are geologic formations (ancient marine embayments) similar to those in Paso Robles throughout France and Italy -- in Tuscany, the Rhone and Bordeaux regions, even Burgundy. Also the southern Adelaida region of Australia has many limestone rock deposits. They are all mainly marine sediments that have weathered into soils over many thousands of years.

MB: In that case, are there differences between central coast and northern California soils?

TR: In terms of soils, all of the California winegrowing regions have a variety of soils, ranging from recent alluvial river deposits and eroded sedimentary layers, to ancient calcareous and siliceous (silica-rich) seabed deposits. But Paso Robles has a thicker deposit of Monterey (Miocene and Pliocene age) and Paso Robles Formations (Pleistocene), which feature calcium carbonate-rich (limestone, calcareous shale and mudstone) and silicate-rich (shales and sandstone) rocks. Sonoma County is on a small wedge of the Pacific Plate, but it contains more of the igneous, granitic and quartz-rich rocks characteristic of the western NA plate; and Napa has more volcanic rocks, such as diabase and basalt.

Napa soils receive more annual moisture, resulting in more weathered, acid soils with higher organic matter. They have low to non-existent calcium carbonate, and typical soil pH’s of 5.0 to 7.0.

Paso Robles is drier and the soils are less highly weathered, covered by less native biomass, and generally have lower organic matter levels. They’re more alkaline, with higher soil pH’s ranging from 6.0 t