Do Biodynamically Grown Grapes

Make Better Wine?

A group of biodynamic farmers and winemakers tried to make a case for their wines at a recent gathering in San Francisco. Alan Goldfarb came to the conference with the belief that just maybe, this is our last and best shot at turning out wines of place. Read his report to see how he felt at the meeting’s end.

by

Alan Goldfarb

November 14, 2007

orget about the gosh-darned cow horns for a second. The folks who produce biodynamic wine – some would call them zealots – would like you to put on the back of the stove all that stuff about the stuffed bovine vessels that are integral to their story. It only gets in the way, they say, of the broader picture.

orget about the gosh-darned cow horns for a second. The folks who produce biodynamic wine – some would call them zealots – would like you to put on the back of the stove all that stuff about the stuffed bovine vessels that are integral to their story. It only gets in the way, they say, of the broader picture.

The big picture here is, of course, what is biodynamic farming as it pertains to wine grape growing, how far has it come, and where is it going? So, let’s give them that. Let’s not fixate on those hollow horns

of a cow (that incidentally, has had at least one calf) and gets buried in the vineyard stuffed with a natural preparation of minerals and dung, and get to the real question:

of a cow (that incidentally, has had at least one calf) and gets buried in the vineyard stuffed with a natural preparation of minerals and dung, and get to the real question:

What the heck does all this have to do with what’s in my glass? What does sprinkling those ingredients from the aforementioned horn, during the precise cycle of the moon, have to do with how a wine tastes? Can I taste the earth or smell the natural elements from that special mixture that was introduced into the soil? (And why would I want to?) But most important, will my wine taste better if the grapes that were grown for that wine were made biodynamically?

A group of biodynamic farmers and biodynamic winemakers, who gathered in the old converted Officer’s Club at the San Francisco Presidio recently, may or may not have answered those questions to the satisfaction of some. But they did show how impassioned they are, and how intelligent they are when speaking about a subject that has engendered growing interest; and good-natured derision.

Did they dispel the skepticism that circulates around the subject? Perhaps. Did they better explain their mission? Probably. Did they make me want to go out and buy a biodynamically made wine, for which I’ll most likely pay a dear price? Maybe.

I still don’t know if biodynamic wines incontrovertibly taste better. A growing cadre of producers (of which there exists only about 30 throughout the U.S., who

At worst, if others begin to make wines this way despite the perceived mumbo-jumbo about how they do it, maybe, just maybe, this is our last and best shot at turning out wines of place.

are certified by Demeter, whose Web site boasts of 3,500 BD producers in 40 countries) have only been making biodynamic wine for about 10 years; a timeframe that is still too early to assess reliably.

But I have to report, that after listening to their reasons for producing such wines, I came away not necessarily convinced, but open to the idea that biodynamics makes sense. At worst, if others begin to make wines this way despite the perceived mumbo-jumbo about how they do it, maybe, just maybe, this is our last and best shot at turning out wines of place. Wines that are anathema to the ever-increasing bottom-line wines and soul-obliterating wines brought to us by corporate capitalism.

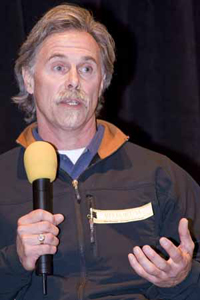

Mike Benziger of Benziger Family Winery in Sonoma County was one of the first progenitors of biodynamic wines. He has been practicing it for about a decade, after his family made millions with the sale to corporate entities of their cash cow, Glen Ellen-brand wines. When I pressed the panel to tell me how biodynamics translates to the bottle, Benziger began to respond with a cliché, but quickly rallied.

Biodynamics he said “Lets the wine do the talking. It would be a tragedy to let anything happen to that. It’s not that biodynamic wine is better, it’s different.

“The consumer does connect with the idea that we’re trying to be best farmers we can be … and have a sense of place.”

Mike Benziger is a pioneer of biodynamic wines.

“We’ve started something that didn’t exist before and we started in the wrong place and we’re trying to get to the right place,” he said.

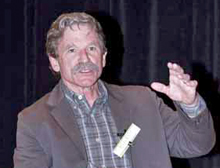

The “wrong place” Dolan explained to APPELLATION AMERICA, is “reductionism.”

“We were trying to break everything down but a farm is a system. We want to create a balance. We’re nurturing the property so it starts to take care of itself. What we really want to be is in a holistic place.”

Randall Grahm, the affable and articulate eccentric of Bonny Doon Vineyards in the Santa Cruz Mountains, put it another way, as is his wont.

“Biodynamics and terroir fit together, but there are distractions,” he surmised. “Biodynamics is a methodology or a practice, but terroir is an ideal, or a value. Biodynamics could be the royal road to terroir … Biodynamics can be thought of as viticultural homeopathy to solve terroir.”

When asked if he started to practice biodynamic farming to get to terroir Grahm, who has often described himself as a “terroirist”, admitted that he sold off some of his brands in order to free himself up to get beyond organic viticulture.

Paul Dolan helped the Fetzer family biodynamically farm some of its Mendocino vineyards.

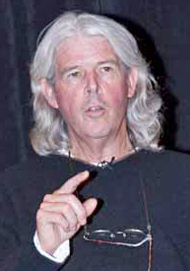

With that, Alan York, a biodynamic guru, who heads up Benziger’s grower relations department, chimed in rhapsodically, “This is where biodynamics can contribute to great wine -- that haunting quality of individuality that beckons you.”

To which Grahm responded, “I say those words all the time, but what does it mean to express the site? This is something that anguishes me. The old-world is privileged to have discovered its terroir.

“In the new-world, we’re just guessing, we’re just guessing. We’re kind of lost, just wandering around. Our value is getting the high-point scores and selling our wines. It’s a vast, vast leap to get to wines that express terroir.”

Interjected York “It’s not just words, but it takes a lot of courage to follow through and it takes a great commitment to do that.”

Continued Grahm, “What is brilliant and beautiful about biodynamics is that you become more (aware) of what you’re doing and expand your imagination and to

Alan York heads up Benziger’s grower relations department.

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,