The Ozark Highlands appellation comprises 1,280,000 acres in south-central Missouri.

A Wine Rite-of-Passage

in the Ozark Highlands

The Ozark Highlands is an appellation without pretension, where the wine speaks for the land and for itself. Come along for an introductory trip on this lesser-known Missouri wine trail.

by

Tim Pingelton

May 5, 2008

nthropologists have written much on the notion of a “liminal” stage in rites of passage. This is the point at which participants pass from their old state of being into a new state of being – you know, like when the fiancée is toted over the threshold, or when the boy becomes a man, or when the outsider joins the club. My buddy Chris came along for a tour of Missouri’s Ozark Highlands appellation, and I played the amateur anthropologist in observing his “liminal” transformation from import wine aficionado to local wine enthusiast.

nthropologists have written much on the notion of a “liminal” stage in rites of passage. This is the point at which participants pass from their old state of being into a new state of being – you know, like when the fiancée is toted over the threshold, or when the boy becomes a man, or when the outsider joins the club. My buddy Chris came along for a tour of Missouri’s Ozark Highlands appellation, and I played the amateur anthropologist in observing his “liminal” transformation from import wine aficionado to local wine enthusiast.

The Ozark Highlands appellation

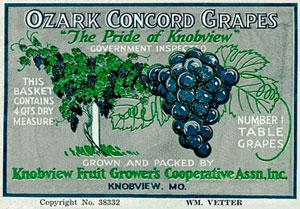

This is just one of several labels used for grapes that were shipped from Rosati (formerly called Knobview), Missouri, during the late 1920s–‘30s. Photo courtesy of www.rosatimo.com

The “highlands” are at about 1100 feet elevation. The fertile, well-drained soil is great for row crops and the production of table grapes, but the acreage for wine grapes has to be tended assiduously to avoid over-production and a subsequent loss in quality. Native American and French-American hybrids thrive in this environment, and these grapes account for a large majority of the wines produced in the Ozark Highlands.

Historic Route 66 runs through the area, and much of the appellation seems unchanged from the highway’s heyday. The famous Wagon Wheel Motel and Finn’s Motel (“Vacancy!” “Family Units!”) still welcome weary motorists. In season, travelers may purchase fresh grapes from plywood grape stands along 66 and its modern successor, Interstate 44. The wineries in the appellation are centered on the St. James/Rosati area, with vineyards surrounding the area. An echoing, retro feel pervades the area, but that is acceptable for grape growing and winemaking, industries that use many tools and techniques that have changed very little in the last century (e.g. small wine presses, oak barrels).

Phyllis Meagher, owner of Meramec Vineyards in St. James, has been updating her winery lately with a new entranceway. Her renovations mirror her wine list - as visitors pass from the somewhat outmoded St. James area and enter the contemporary interior of her tasting room/bistro, so, too, the printed wine list moves from “Euro Tradition” to “American Tradition.” Phyllis personally tends her 60 acres of vineyard.

“Euro Tradition” wines include Norton, Vignoles, two white blends, and a red blend. The “American Tradition” wines include blends of native grapes (Concord, Catawba, Stark Star, and Niagara) and French-American blends (Vidal Blanc and Cayuga).

“Euro Tradition” wines include Norton, Vignoles, two white blends, and a red blend. The “American Tradition” wines include blends of native grapes (Concord, Catawba, Stark Star, and Niagara) and French-American blends (Vidal Blanc and Cayuga).

The “Euro” wines are named such not because of their vinification but because they are made of French-American hybrid grapes. They carry distinct expressions of each varietal, even in the blends. The “American” wines evoke thoughts of picnics by a river, lounging under a big cottonwood in the summertime. These are fun, unabashedly Middle-American wines.

The tasting room/bistro is large, airy, and very pleasant, and Phyllis hosts occasional dinners (e.g. trout dinner, harvest moon festival) with a talented visiting chef. Phyllis is a strong proponent of the Missouri wine industry and a good friend. She took us to the production area to taste her yet to be bottled Stark Star port. Had I not known it was a port, I might have thought it was an unfortified dessert wine. This is a great port for those leery of heavy oxidized tones in port.

About 300 yards from Meramec Vineyards is the St. James Winery, the largest wine producer in Missouri, producing about 180,000 cases of wine per year. The exterior of the winery evokes its 1970’s founding, featuring a large sign in groovy lettering in front of a large dark-red, wood-clad warehouse-style building. Stepping over the threshold, Chris was shocked at the sight of cases and bottles of wines in bold, bright colors. Color-saturated labels with undulating Thomas Hart Benton-esque images were on bottles of a variety of colors, with lime green and sunny yellow capsules topping the bottles. Silver buckets gleamed on the shiny tasting counter, and it took a minute to get our bearings.

We were met by Ron Townley, cellar supervisor at St. James Winery, who showed us into the extensive production area. Standing in front of imposing 5000-gallons tanks with

The production area at St. James Winery.

With over 35 products on their wine and juice list, the self-serve set-up of their tasting bar was convenient, if not unexpected. Chris and I discussed how a certain Seyval Blanc is more steely than a fruiter one from a different vintage. All of their wines are good, and they really do have something to please just about anyone. Those seeking sophisticated old-world wines might not find their wine (although their Cynthiana comes close), but, judging from the labeling and vinification style, that is not what St. James Winery is after. After all, their trademarked slogan is “America’s Midwest Winery.” Their distribution carries into 14 states, and the winery has a total of over 500 vineyard acres, with satellite vineyards in Arkansas and Michigan.

After poking around St. James and having lunch, we headed on to Heinrichshaus Vineyard and Winery. Despite Chris’ proven navigational skills, the winery was not easy to find. The light, cold rain didn’t help. As Chris discussed his growing knowledge of Missouri wines, we finally spotted the tiny sign denoting Heinrichshaus. Then we hit another liminal point. Pulling up the drive, I felt suddenly removed to a chalet somewhere in the Tyrolean alps. The entire winery was the size of the St. James Winery tasting area.

Stepping into Heinrichshaus wa

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,