Thirty years ago Red Mountain looked like this minus the vineyards. John Williams transformed the barren land into prime wine country.

Kiona Vineyards

John Williams boldly went where no one had gone before.

Welcome to Red Mountain.

by

Anne Sampson

November 28, 2008

Appellation America: In 1975 when you planted Kiona, Red Mountain was completely undeveloped. You could have invested in an established vineyard. Why did you choose Red Mountain instead?

John Williams (JW): We decided that, number one, this piece of land was available, and number two, it was not going

Scott (left) and John Williams in the tasting room of Kiona Vineyards and Winery. to cost us a whole lot. We considered some land that had water, but the vineyards that were available didn’t give us enough room for expansion. We looked at this land very closely. In the late ’20s and early ‘30s, the whole Columbia Basin of eastern Washington was surveyed in terms of topography and the soils. We had good information on what kind of soil was there, what kind of crops would grow on these soils, and the water holding capacity. From a scientific standpoint, it wasn’t just a shot in the dark. The soils were rated well for growing grapes.

AA: Red Mountain was entirely undeveloped at the time. Were there challenges you didn’t anticipate?

JW: We had to bring in power from Benton City, and grade a road across the desert, and drill a well. We couldn’t get financing, so we used our own money to drill the well. We’d researched it and knew there was water about some 500 feet deep. We were at 550 feet and close to the end of our cash, and we hadn’t hit water yet, and the well driller asked us how far we wanted to go. We asked, how much money have we got left? We drilled about five more feet and hit the water. When people ask me how deep are the wells, I say mine are about a hundred thousand dollars deep.

Scott Williams (SW): When we started making wine in 1980, there were no wine consultants, there were no warehouses, there were no mobile bottling lines, there was nothing. You just had to figure out how to do it yourself. Every step along the way – you’ve got all this time and money invested, and if you didn’t take the next step, you had to quit, because there was nobody who wanted to buy it. At the time, there was no market for it. You either had to succeed or fail.

AA: No road, no power, no neighbors – what convinced you that this venture would be successful?

JW: We succeeded because we were optimists, we wanted to do it. We knew the grapes would be good because the research had already been published. The first grapes that we planted were Cabernet Sauvignon, White Riesling and Chardonnay. Those were classic varieties, and the research said they all had very good properties to them.

AA: You’ve expanded far beyond the original 12 acres, and added a lot of other varieties along the way. What would you say is Kiona’s greatest strength today?

JW: About 80 percent of our vineyard is covered in Hezel silt loam, which is about the lightest soil there is, and probably some of the best for growing grapes.

SW: Actually, that particular soil profile is the best for Cabernet, and our Cabs have done very well over the years. Most of our acreage is in Cabernet and Merlot. The ’99 Cabernet and the ’92 Merlot were both listed in Wine Spectator’s Top 100 wines.

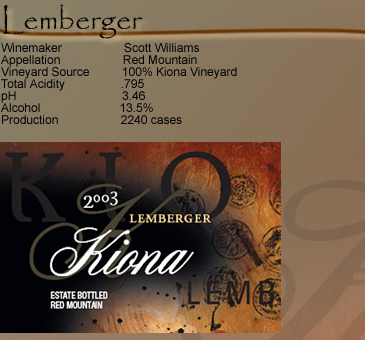

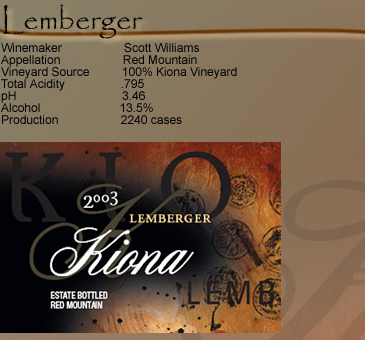

The Austrian grape Lemberger is a late-ripening variety which produces red wines that are typically rich in tannin and may exhibit a pronounced spicy character.

AA: You’ve also got quite a bit of acreage devoted to Lemberger. In fact, in 1980, you produced the first commercial vintage in the United States, and it makes up about 10 percent of your total production today. It’s become something of a trademark for you. Why did you choose to plant Lemberger?

JW: We’ve always grown great Cabernet here, but a lot of people grow great Cabernet. And when wine writers came through, they always wanted to write about something different.

SW: In any business, the opportunity to be first with something is pretty rare. Just the idea of planting a variety that was not available anywhere in the United States was pretty attractive.

AA: So which is the higher quality wine, your Lemberger or your Cabernet?

SW: They’re both high quality, but they’re different. Stylistically, the Cabernet is a big, brawny, long-lived traditional style of wine, and it does very well here. The Lemberger style is a lot simpler, but that doesn’t make it lower quality. It’s an easier wine to drink than Cabernet, if you’re just sitting around enjoying a glass of wine. Cabernet really needs to be enjoyed with food.

JW: Some of my favorite wine is Cabernet, but I probably drink more Lemberger.

AA: Scott, you’ve grown up in the wine business, working and learning alongside your father and Jim Holmes. You took over as winemaker in 1990. How has your winemaking style evolved over the years?

SW: We’ve diversified in our red wines. We used to make one tank of each variety. We had a fairly old-technology press, and we’d press it as hard as we could. It would all go into one tank, and several years later you could drink it. I see that quite a lot now, where people are trying to make very extracted, very powerful wines with lots of tannins. It tastes just like what we made in the late ‘80s.

But we bought a press in 1995 that is much, much gentler. It presses up to 14 psi, where the old one went up to 100 psi. And we fractionalize the wine; anything we can pump off without pressing goes into our newest, best barrels, and we keep them separate by vineyard lots and by variety. Then we press very gently the first fractions and we put that all together and put it into barrels. The rest we press the heck out of. We might blend that back in later for color or structure.

But we bought a press in 1995 that is much, much gentler. It presses up to 14 psi, where the old one went up to 100 psi. And we fractionalize the wine; anything we can pump off without pressing goes into our newest, best barrels, and we keep them separate by vineyard lots and by variety. Then we press very gently the first fractions and we put that all together and put it into barrels. The rest we press the heck out of. We might blend that back in later for color or structure.

We spend a lot of money on barrels. The barrels add structure and tannins. We don’t really need any more tannins, and we have plenty of extraction, so what we’re looking for in a barrel is one that is matched to specific vineyard lots. In our Cabernet, we’re looking for barrels that give elegance and subtlety, as opposed to power and structure. In another spot we might want to reverse that, so we’ll put it in a different barrel. The only way to figure that out is to buy barrels, put wine into them, and take notes.

JW: It takes a lot more barrels and a lot more time, thus the need for a dedicated barrel room.

AA: How do you characterize Red Mountain fruit today?

SW: The wines are very, very d

John Williams (JW): We decided that, number one, this piece of land was available, and number two, it was not going

Scott (left) and John Williams in the tasting room of Kiona Vineyards and Winery.

AA: Red Mountain was entirely undeveloped at the time. Were there challenges you didn’t anticipate?

JW: We had to bring in power from Benton City, and grade a road across the desert, and drill a well. We couldn’t get financing, so we used our own money to drill the well. We’d researched it and knew there was water about some 500 feet deep. We were at 550 feet and close to the end of our cash, and we hadn’t hit water yet, and the well driller asked us how far we wanted to go. We asked, how much money have we got left? We drilled about five more feet and hit the water. When people ask me how deep are the wells, I say mine are about a hundred thousand dollars deep.

Scott Williams (SW): When we started making wine in 1980, there were no wine consultants, there were no warehouses, there were no mobile bottling lines, there was nothing. You just had to figure out how to do it yourself. Every step along the way – you’ve got all this time and money invested, and if you didn’t take the next step, you had to quit, because there was nobody who wanted to buy it. At the time, there was no market for it. You either had to succeed or fail.

AA: No road, no power, no neighbors – what convinced you that this venture would be successful?

JW: We succeeded because we were optimists, we wanted to do it. We knew the grapes would be good because the research had already been published. The first grapes that we planted were Cabernet Sauvignon, White Riesling and Chardonnay. Those were classic varieties, and the research said they all had very good properties to them.

AA: You’ve expanded far beyond the original 12 acres, and added a lot of other varieties along the way. What would you say is Kiona’s greatest strength today?

JW: About 80 percent of our vineyard is covered in Hezel silt loam, which is about the lightest soil there is, and probably some of the best for growing grapes.

SW: Actually, that particular soil profile is the best for Cabernet, and our Cabs have done very well over the years. Most of our acreage is in Cabernet and Merlot. The ’99 Cabernet and the ’92 Merlot were both listed in Wine Spectator’s Top 100 wines.

The Austrian grape Lemberger is a late-ripening variety which produces red wines that are typically rich in tannin and may exhibit a pronounced spicy character.

JW: We’ve always grown great Cabernet here, but a lot of people grow great Cabernet. And when wine writers came through, they always wanted to write about something different.

SW: In any business, the opportunity to be first with something is pretty rare. Just the idea of planting a variety that was not available anywhere in the United States was pretty attractive.

AA: So which is the higher quality wine, your Lemberger or your Cabernet?

SW: They’re both high quality, but they’re different. Stylistically, the Cabernet is a big, brawny, long-lived traditional style of wine, and it does very well here. The Lemberger style is a lot simpler, but that doesn’t make it lower quality. It’s an easier wine to drink than Cabernet, if you’re just sitting around enjoying a glass of wine. Cabernet really needs to be enjoyed with food.

JW: Some of my favorite wine is Cabernet, but I probably drink more Lemberger.

AA: Scott, you’ve grown up in the wine business, working and learning alongside your father and Jim Holmes. You took over as winemaker in 1990. How has your winemaking style evolved over the years?

SW: We’ve diversified in our red wines. We used to make one tank of each variety. We had a fairly old-technology press, and we’d press it as hard as we could. It would all go into one tank, and several years later you could drink it. I see that quite a lot now, where people are trying to make very extracted, very powerful wines with lots of tannins. It tastes just like what we made in the late ‘80s.

But we bought a press in 1995 that is much, much gentler. It presses up to 14 psi, where the old one went up to 100 psi. And we fractionalize the wine; anything we can pump off without pressing goes into our newest, best barrels, and we keep them separate by vineyard lots and by variety. Then we press very gently the first fractions and we put that all together and put it into barrels. The rest we press the heck out of. We might blend that back in later for color or structure.

But we bought a press in 1995 that is much, much gentler. It presses up to 14 psi, where the old one went up to 100 psi. And we fractionalize the wine; anything we can pump off without pressing goes into our newest, best barrels, and we keep them separate by vineyard lots and by variety. Then we press very gently the first fractions and we put that all together and put it into barrels. The rest we press the heck out of. We might blend that back in later for color or structure.

We spend a lot of money on barrels. The barrels add structure and tannins. We don’t really need any more tannins, and we have plenty of extraction, so what we’re looking for in a barrel is one that is matched to specific vineyard lots. In our Cabernet, we’re looking for barrels that give elegance and subtlety, as opposed to power and structure. In another spot we might want to reverse that, so we’ll put it in a different barrel. The only way to figure that out is to buy barrels, put wine into them, and take notes.

JW: It takes a lot more barrels and a lot more time, thus the need for a dedicated barrel room.

AA: How do you characterize Red Mountain fruit today?

SW: The wines are very, very d

took charge of neighboring Ciel du Cheval Vineyard. Today John and his son Scott manage Kiona’s 300 acres of grapes, including the original 12 acres planted more than 30 years ago, and produce some 30,000 cases a year of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Syrah, Lemberger, Chardonnay, Chenin Blanc, Riesling, and Gewurztraminer, all encased in a 10,000-square-foot barrel room carved out of the mountain below Kiona’s expansive tasting room.

took charge of neighboring Ciel du Cheval Vineyard. Today John and his son Scott manage Kiona’s 300 acres of grapes, including the original 12 acres planted more than 30 years ago, and produce some 30,000 cases a year of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Syrah, Lemberger, Chardonnay, Chenin Blanc, Riesling, and Gewurztraminer, all encased in a 10,000-square-foot barrel room carved out of the mountain below Kiona’s expansive tasting room.

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,