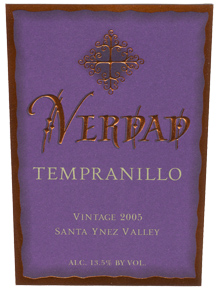

Along with Albariño, Tempranillo is among the Spanish varietals Verdad winemaker Louisa Sawyer Lindquist is making popular in the U.S.

Verdad Winery is Champion of Spanish Varietals

"Spanish varietals in California seemed like a `natural' to me."

~Louisa Sawyer Lindquist

by

Dennis Schaefer

August 31, 2007

Dennis Schaefer (DS): Why Albariño? And why now?

Louisa Sawyer Lindquist (LSL): First, the brief answer. Albariño is a great grape that can produce a wine with gorgeous aromatics, mineral/citrus flavors and lively acidity. It's a wonderful food wine and it shines with seafood, especially shellfish. To me, it's always tasted of the sea, with hints of brine, orange, lime blossoms, minerals and a hint of bitter almond.

flavors and lively acidity. It's a wonderful food wine and it shines with seafood, especially shellfish. To me, it's always tasted of the sea, with hints of brine, orange, lime blossoms, minerals and a hint of bitter almond.

And it struck me that a lot of California looked similar to many areas of Spain: it had a strong Spanish influenced history, architecture and geographical names, yet no Spanish varietal wines. I really was surprised that no one had thought of it. It seemed like a "natural" to me.

Actually, the project is eleven years old this year (first vines planted in 1996) and I've loved Albariño since I first tasted it in 1990. Now the vineyard has some maturity and is producing great fruit. My experience working with the grape for seven vintages has helped make better wines.

DS: You obviously think the wine drinking public is ready for Albariño. Isn't Albariño at the same stage of public awareness that Viognier was about ten years ago?

LSL: Some of the wine drinking public is always ready for new flavor profiles. Albariño is like a breath of fresh air...or should I say a burst of racy acidity and balance that has been embraced by many as a refreshing alternative to the very ripe, unctuous style that has become the trademark of California wines.

Albariño has about the same level of familiarity that Viognier had ten years ago. However, Albariño has a completely different flavor profile than Viognier. They share lovely aromatics but Albariño is more subtle and restrained than Viognier; because it's not as big and unctuous as Viognier, it will not become as popular.

DS: How has your Albariño been received? Have you found it's an educational process for many people in becoming familiar with the varietal?

LSL: It has been an educational process. In the last couple years, Albariño and other Spanish wines as well as food, especially tapas, have exploded. It seems everything Spanish has become popular and now more domestic wineries are working with Albariño and Tempranillo, which is all beneficial to me. I think I'm a bit ahead of the curve because I've had a few years to figure out what works for me, though every vintage presents new challenges. I think Albariño will always be a "niche" wine with a devoted following and that's fine with me.

Verdad Albariño has been very well received by the trade and especially restaurant wine buyers because it compliments food so well. Its firm acidity and balance marry well with food, seafood in particular, and it doesn't overwhelm dishes like a lot of the big "fruit bombs" that smother subtle flavors.

DS: Did you feel you had an advantage over other California producers, who came later to the Spanish varietal game?

LSL: Yes and no - because Verdad started out so small, and is still small - just a few hundred cases of Albariño and not much more Tempranillo, plus Rosé - there hasn't been a tremendous impact on the market. I've been under the radar, intentionally really; because although the wines are really quite good, I dream of making world class wines and that doesn't happen overnight. The advantage of starting small and gradually increasing production is that it gives me a greater opportunity to know the grapes and improve vineyard practices and winemaking to create wines that will be the best they can be. So I have had an earlier, ongoing education, compared to people new to the Albariño/Tempranillo scene.

DS: Verdad (and Havens) was the first to produce an Albariño in California; did that help or hurt you? Did you feel you had developed a sustainable, first mover niche?

LSL: It certainly didn't hurt. Luckily the first wines turned out to be quite tasty. It was fun to sell it as the first Albariño and to turn on buyers and consumers to something with a different flavor profile: lighter, lower in alcohol and more food friendly than the stereotypical white wine, and made in California. Restaurants, especially in San Francisco and New York were quite enthusiastic and that was gratifying, especially since they're such competitive markets. As far as a first mover niche goes, I don't think that title is sustainable. The first mover niche will move to the next 'new varietal' grown in California. I'm sticking to what I'm beginning to know best.

DS: What made you think you could successfully plant Albariño and Tempranillo, and fashion varietally true wines in Santa Barbara County?

LSL: I had no idea about Albariño, really. That was a case of serendipity! Brian Babcock had planted some Albariño from vines he got in Rias Baixas and sold us some bud wood around the time Bob Lindquist (Qupé Wine Cellars) and I had declared our love for Albariño (and each other) in 1996/7.

I am very lucky because the vineyard site where Albariño and Tempranillo are grown in Santa Ynez Valley, the Ibarra-Young Vineyard in Los Olivos, is a relatively cool region II bordering on region III, which has a strong marine influence that keeps the evenings, nights and mornings quite cool. It keeps the acidity on the higher side to produce balanced and varietally correct wines.

bordering on region III, which has a strong marine influence that keeps the evenings, nights and mornings quite cool. It keeps the acidity on the higher side to produce balanced and varietally correct wines.

The winemaking choice to keep Albariño true to its roots is to pick relatively early, so the sugar is moderate and balanced with a firm acidity. By picking early, which normally is the first week or so in September, the grapes have lower alcohol potential, good acidity and balance. My recent vintages were picked at 22 degrees Brix, between 3.17 and 3.20 pH and between 8.4 and 8.55 total acidity.

In Rias Baixas, they don't always achieve even 22 degrees Brix: that would be considered an exceptional vintage there, so I am lucky to get such good balance from vines that almost regulate themselves to about 3 tons per acre.

Both these vineyard sites (Ibarra-Young in Los Olivos & Sawyer Lindquist in Edna Valley) have many geographic characteristics in common with the Rioja Alta region in Rioja, specifically the marine influence and topography. The soil in Rioja has a different composition, of course. That being said, the jury is still out on Tempranillo. Every vintage has been different at Ibarra-Young Vineyard and the vines are evolving as they mature. Our Sawyer Lindquist Vineyard in Edna Valley has yet to bear fruit, so we shall see.

DS: Randall Grahm of Bonny Doon says that "giving Albariño grapes a tad more shade (in his Monterey County vineyard) produces grapes with thicker skins, and thus lowers phenolics, preserving delicate aromatics and finesse." What is your experience?

LSL: The Albariño planted at Ibarra-Young vineyard in Los Olivos has alwa

Louisa Sawyer Lindquist (LSL): First, the brief answer. Albariño is a great grape that can produce a wine with gorgeous aromatics, mineral/citrus

flavors and lively acidity. It's a wonderful food wine and it shines with seafood, especially shellfish. To me, it's always tasted of the sea, with hints of brine, orange, lime blossoms, minerals and a hint of bitter almond.

flavors and lively acidity. It's a wonderful food wine and it shines with seafood, especially shellfish. To me, it's always tasted of the sea, with hints of brine, orange, lime blossoms, minerals and a hint of bitter almond.

And it struck me that a lot of California looked similar to many areas of Spain: it had a strong Spanish influenced history, architecture and geographical names, yet no Spanish varietal wines. I really was surprised that no one had thought of it. It seemed like a "natural" to me.

Actually, the project is eleven years old this year (first vines planted in 1996) and I've loved Albariño since I first tasted it in 1990. Now the vineyard has some maturity and is producing great fruit. My experience working with the grape for seven vintages has helped make better wines.

DS: You obviously think the wine drinking public is ready for Albariño. Isn't Albariño at the same stage of public awareness that Viognier was about ten years ago?

LSL: Some of the wine drinking public is always ready for new flavor profiles. Albariño is like a breath of fresh air...or should I say a burst of racy acidity and balance that has been embraced by many as a refreshing alternative to the very ripe, unctuous style that has become the trademark of California wines.

Albariño has about the same level of familiarity that Viognier had ten years ago. However, Albariño has a completely different flavor profile than Viognier. They share lovely aromatics but Albariño is more subtle and restrained than Viognier; because it's not as big and unctuous as Viognier, it will not become as popular.

DS: How has your Albariño been received? Have you found it's an educational process for many people in becoming familiar with the varietal?

LSL: It has been an educational process. In the last couple years, Albariño and other Spanish wines as well as food, especially tapas, have exploded. It seems everything Spanish has become popular and now more domestic wineries are working with Albariño and Tempranillo, which is all beneficial to me. I think I'm a bit ahead of the curve because I've had a few years to figure out what works for me, though every vintage presents new challenges. I think Albariño will always be a "niche" wine with a devoted following and that's fine with me.

Verdad Albariño has been very well received by the trade and especially restaurant wine buyers because it compliments food so well. Its firm acidity and balance marry well with food, seafood in particular, and it doesn't overwhelm dishes like a lot of the big "fruit bombs" that smother subtle flavors.

DS: Did you feel you had an advantage over other California producers, who came later to the Spanish varietal game?

LSL: Yes and no - because Verdad started out so small, and is still small - just a few hundred cases of Albariño and not much more Tempranillo, plus Rosé - there hasn't been a tremendous impact on the market. I've been under the radar, intentionally really; because although the wines are really quite good, I dream of making world class wines and that doesn't happen overnight. The advantage of starting small and gradually increasing production is that it gives me a greater opportunity to know the grapes and improve vineyard practices and winemaking to create wines that will be the best they can be. So I have had an earlier, ongoing education, compared to people new to the Albariño/Tempranillo scene.

DS: Verdad (and Havens) was the first to produce an Albariño in California; did that help or hurt you? Did you feel you had developed a sustainable, first mover niche?

LSL: It certainly didn't hurt. Luckily the first wines turned out to be quite tasty. It was fun to sell it as the first Albariño and to turn on buyers and consumers to something with a different flavor profile: lighter, lower in alcohol and more food friendly than the stereotypical white wine, and made in California. Restaurants, especially in San Francisco and New York were quite enthusiastic and that was gratifying, especially since they're such competitive markets. As far as a first mover niche goes, I don't think that title is sustainable. The first mover niche will move to the next 'new varietal' grown in California. I'm sticking to what I'm beginning to know best.

DS: What made you think you could successfully plant Albariño and Tempranillo, and fashion varietally true wines in Santa Barbara County?

LSL: I had no idea about Albariño, really. That was a case of serendipity! Brian Babcock had planted some Albariño from vines he got in Rias Baixas and sold us some bud wood around the time Bob Lindquist (Qupé Wine Cellars) and I had declared our love for Albariño (and each other) in 1996/7.

I am very lucky because the vineyard site where Albariño and Tempranillo are grown in Santa Ynez Valley, the Ibarra-Young Vineyard in Los Olivos, is a relatively cool region II

bordering on region III, which has a strong marine influence that keeps the evenings, nights and mornings quite cool. It keeps the acidity on the higher side to produce balanced and varietally correct wines.

bordering on region III, which has a strong marine influence that keeps the evenings, nights and mornings quite cool. It keeps the acidity on the higher side to produce balanced and varietally correct wines.

The winemaking choice to keep Albariño true to its roots is to pick relatively early, so the sugar is moderate and balanced with a firm acidity. By picking early, which normally is the first week or so in September, the grapes have lower alcohol potential, good acidity and balance. My recent vintages were picked at 22 degrees Brix, between 3.17 and 3.20 pH and between 8.4 and 8.55 total acidity.

In Rias Baixas, they don't always achieve even 22 degrees Brix: that would be considered an exceptional vintage there, so I am lucky to get such good balance from vines that almost regulate themselves to about 3 tons per acre.

Both these vineyard sites (Ibarra-Young in Los Olivos & Sawyer Lindquist in Edna Valley) have many geographic characteristics in common with the Rioja Alta region in Rioja, specifically the marine influence and topography. The soil in Rioja has a different composition, of course. That being said, the jury is still out on Tempranillo. Every vintage has been different at Ibarra-Young Vineyard and the vines are evolving as they mature. Our Sawyer Lindquist Vineyard in Edna Valley has yet to bear fruit, so we shall see.

DS: Randall Grahm of Bonny Doon says that "giving Albariño grapes a tad more shade (in his Monterey County vineyard) produces grapes with thicker skins, and thus lowers phenolics, preserving delicate aromatics and finesse." What is your experience?

LSL: The Albariño planted at Ibarra-Young vineyard in Los Olivos has alwa

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,