Fall colors in the vineyards add to the splendor

of Missouri’s Augusta appellation.

The Soul of Augusta

At the heart of the terroir in America’s first appellation, is something much more special than the uniqueness of the soils and climate.

by

Tim Pingelton

December 8, 2005

“The name of the viticultural area described in this section is ‘Augusta.’”

So reads the first sentence of the Code of Federal Regulations, Title 27, Volume 1, Part 9, Section 9.22 of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms. This federal ruling declared the Augusta, Missouri area to be the first officially named “American Viticultural Area” (AVA). Wineries within this approximately 15 square-mile area may designate “Augusta” as their wines’ place of origin. Around the world, this distinction might not carry the weight of “Napa” or “Sonoma,” but the four Augusta wineries take great pride in their appellation.

Augusta is situated inside a bend on the north bank of the Missouri River about 40 miles west of St. Louis in St. Charles County. Where California has “Valleys,” Missouri has “Bottoms.” The strip of land adjacent to the river in Augusta is called the “Hancock Bottom,” but most vineyard acreage is up from this alluvial plain. The soil along much of the Missouri River as it winds its way through the state is known as “Hayne Silt-Loam.” In general, this soil is more heavily clay in lower elevations and more silty at higher elevations. The clay zones often have drainage problems, but the silty areas are very root-friendly to grape vines. Elevation rises from the river slowly in Augusta, and grapes planted on these gentle slopes enjoy effective air and water drainage. Silt and rocks in the soil radiate warmth collected during the day to help ease spring blooming.

Elevation rises from the river slowly in Augusta, and grapes planted on these gentle slopes enjoy effective air and water drainage. Silt and rocks in the soil radiate warmth collected during the day to help ease spring blooming.

The Augusta vineyard soil is unique in that it is new. Augusta (originally called Mount Pleasant) was settled in the 1830’s by followers of Daniel Boone. Boone’s Missouri home (bigger than you would think) is a few miles away in Defiance, Missouri, a town with a few good wineries of its own (though outside of the boundaries of the Augusta AVA). The early settlers chose the Augusta site for its excellent river access. A boat landing was built, and the town grew. The boat landing was heavily used, shared by farmers and merchants sending grain, cattle, and wine to all points east and south. A flood in the 1870’s destroyed the landing and actually changed the river’s course. This turned out to be very beneficial to Augusta because several hundred acres of fertile river bottom were exposed. The “new” land was quickly patterned with budding crops and vines.

Augusta is suitable as America’s first named appellation because its soil and environmental characteristics (a combination many wine buffs call “terroir”) are unique to the geographic area, and wines produced here carry those unique characteristics into the wine glass. The Code of Federal Regulations' Final Ruling document, however, needs an important subjective amendment. In his 1998 book Terroir, author James E. Wilson defines terroir thusly:

I saw a winery owner in Augusta wince as a bus-load of visitors disembarked in the winery parking lot. This bunch of 40-ish revelers could mean big sales, so I studied the winery owner to ascertain why he was almost dreading their entrance into his winery. At Missouri wineries on the weekends, it is always someone’s 40th birthday. This usually means funny hats and lines at the bathrooms. A few guys will roll down the hill sloping to the vineyard, but their wives cannot be coaxed to join in. At some time, the partiers will be sentimentally rapt by the lyrics the solo guitarist is singing, but the moment will end when one of the hill-rollers knocks over someone else’s glass.

These things do not affect the winery owner, however. He loves it when these groups visit not only for sales potential but because he likes to see people happy. His fraction of dread comes from the irreverence shown by some of these visitors. Wineries should be fun, happy places, he thinks. They must be. But a certain amount of respect should be felt for the wonder of what went into those ounces of Chambourcin dripping off the tempered glass table top back into the ground.

I asked Gloria, an employee at Augusta Winery, which of their wines she most preferred. She was stumped to the point of paralysis. She saw a customer purchasing a bottle of their blackberry wine (100% fermented berries, no syrup or artificial flavorings), and spoke on that wine. She said quite a few “young people” buy bottles of that and their raspberry wine. They blend ½ cup of the wine with 2 cups of ice-cream (vanilla with the blackberry and chocolate with the raspberry). I made a disdainful comment, equating that mixture to fine old whiskey mixed into cola.

Gloria, on the contrary, countered that these “kids” were just having fun with the wine. That particular wine is a fun wine, she said. They were not disrespecting it or trying to overcome its character. That conversation taught me much about how appellation is perceived in Augusta.

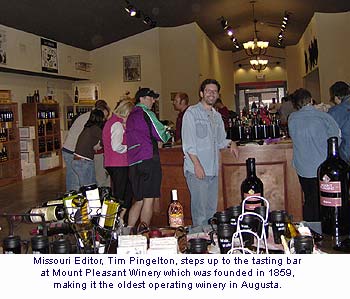

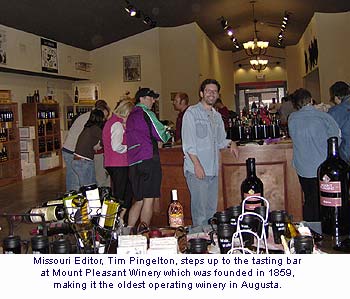

At the Mount Pleasant Winery in Augusta, employees Keith and Keri seemed to take personal pride in the fact that they are part of one of the very few wineries in the Midwest that is able to make a good, estate grown Cabernet Sauvignon. Their 2003 Chardonnay is good, too, with French oak foiled by just a suggestion of diacetyl butteriness (which can be distracting in large amounts). Despite his youth and showmanship (I think I saw him juggling corks), Keith was not working from a script. He held personal conviction in his tasting outcomes, yet he did not press his evaluations on customers.

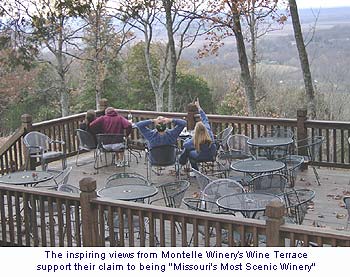

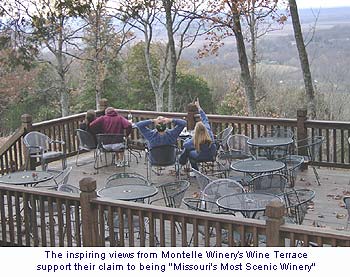

Down the road and up a hill at the Montelle Winery, it is no wonder employees Leann and James are engaged to be married. They are both eager for wine knowledge, Leann for personal fulfillment and James to elucidate customers. James wasn’t satisfied with defining “dry” as “not sweet,” and we finally came to an agreeable definition after discussing numerous aspects of winemaking and organoleptic evaluation. Montelle bills itself as “Missouri’s Most Scenic Winery,” which it very well may be, but, here too, the wine and all it means is the real feature.

So reads the first sentence of the Code of Federal Regulations, Title 27, Volume 1, Part 9, Section 9.22 of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms. This federal ruling declared the Augusta, Missouri area to be the first officially named “American Viticultural Area” (AVA). Wineries within this approximately 15 square-mile area may designate “Augusta” as their wines’ place of origin. Around the world, this distinction might not carry the weight of “Napa” or “Sonoma,” but the four Augusta wineries take great pride in their appellation.

Augusta is situated inside a bend on the north bank of the Missouri River about 40 miles west of St. Louis in St. Charles County. Where California has “Valleys,” Missouri has “Bottoms.” The strip of land adjacent to the river in Augusta is called the “Hancock Bottom,” but most vineyard acreage is up from this alluvial plain. The soil along much of the Missouri River as it winds its way through the state is known as “Hayne Silt-Loam.” In general, this soil is more heavily clay in lower elevations and more silty at higher elevations. The clay zones often have drainage problems, but the silty areas are very root-friendly to grape vines.

Elevation rises from the river slowly in Augusta, and grapes planted on these gentle slopes enjoy effective air and water drainage. Silt and rocks in the soil radiate warmth collected during the day to help ease spring blooming.

Elevation rises from the river slowly in Augusta, and grapes planted on these gentle slopes enjoy effective air and water drainage. Silt and rocks in the soil radiate warmth collected during the day to help ease spring blooming.

The Augusta vineyard soil is unique in that it is new. Augusta (originally called Mount Pleasant) was settled in the 1830’s by followers of Daniel Boone. Boone’s Missouri home (bigger than you would think) is a few miles away in Defiance, Missouri, a town with a few good wineries of its own (though outside of the boundaries of the Augusta AVA). The early settlers chose the Augusta site for its excellent river access. A boat landing was built, and the town grew. The boat landing was heavily used, shared by farmers and merchants sending grain, cattle, and wine to all points east and south. A flood in the 1870’s destroyed the landing and actually changed the river’s course. This turned out to be very beneficial to Augusta because several hundred acres of fertile river bottom were exposed. The “new” land was quickly patterned with budding crops and vines.

Augusta is suitable as America’s first named appellation because its soil and environmental characteristics (a combination many wine buffs call “terroir”) are unique to the geographic area, and wines produced here carry those unique characteristics into the wine glass. The Code of Federal Regulations' Final Ruling document, however, needs an important subjective amendment. In his 1998 book Terroir, author James E. Wilson defines terroir thusly:

- The true concept is not easily grasped but includes physical elements of the vineyard habitat -- the vine, subsoil, drainage, and microclimate. Beyond the measurable ecosystem, there is an additional dimension -- the spiritual aspect that recognizes the joys, the heartbreaks, the pride, the sweat, and the frustration of its history.

I saw a winery owner in Augusta wince as a bus-load of visitors disembarked in the winery parking lot. This bunch of 40-ish revelers could mean big sales, so I studied the winery owner to ascertain why he was almost dreading their entrance into his winery. At Missouri wineries on the weekends, it is always someone’s 40th birthday. This usually means funny hats and lines at the bathrooms. A few guys will roll down the hill sloping to the vineyard, but their wives cannot be coaxed to join in. At some time, the partiers will be sentimentally rapt by the lyrics the solo guitarist is singing, but the moment will end when one of the hill-rollers knocks over someone else’s glass.

These things do not affect the winery owner, however. He loves it when these groups visit not only for sales potential but because he likes to see people happy. His fraction of dread comes from the irreverence shown by some of these visitors. Wineries should be fun, happy places, he thinks. They must be. But a certain amount of respect should be felt for the wonder of what went into those ounces of Chambourcin dripping off the tempered glass table top back into the ground.

I asked Gloria, an employee at Augusta Winery, which of their wines she most preferred. She was stumped to the point of paralysis. She saw a customer purchasing a bottle of their blackberry wine (100% fermented berries, no syrup or artificial flavorings), and spoke on that wine. She said quite a few “young people” buy bottles of that and their raspberry wine. They blend ½ cup of the wine with 2 cups of ice-cream (vanilla with the blackberry and chocolate with the raspberry). I made a disdainful comment, equating that mixture to fine old whiskey mixed into cola.

Gloria, on the contrary, countered that these “kids” were just having fun with the wine. That particular wine is a fun wine, she said. They were not disrespecting it or trying to overcome its character. That conversation taught me much about how appellation is perceived in Augusta.

At the Mount Pleasant Winery in Augusta, employees Keith and Keri seemed to take personal pride in the fact that they are part of one of the very few wineries in the Midwest that is able to make a good, estate grown Cabernet Sauvignon. Their 2003 Chardonnay is good, too, with French oak foiled by just a suggestion of diacetyl butteriness (which can be distracting in large amounts). Despite his youth and showmanship (I think I saw him juggling corks), Keith was not working from a script. He held personal conviction in his tasting outcomes, yet he did not press his evaluations on customers.

Down the road and up a hill at the Montelle Winery, it is no wonder employees Leann and James are engaged to be married. They are both eager for wine knowledge, Leann for personal fulfillment and James to elucidate customers. James wasn’t satisfied with defining “dry” as “not sweet,” and we finally came to an agreeable definition after discussing numerous aspects of winemaking and organoleptic evaluation. Montelle bills itself as “Missouri’s Most Scenic Winery,” which it very well may be, but, here too, the wine and all it means is the real feature.

Print this article | Email this article | More about Augusta | More from Tim Pingelton