Identifying Napa Valley’s individual AVAs by name

will go a long way towards promoting a better understanding

of Napa’s diversity in terroir.

AVA Signage in the Napa Valley

“The typical Napa visitor is a more sophisticated wine visitor than your average Safeway customer. They’re interested in defining different AVAs.”

~ Doug Burnett, Oak Knoll District winegrower

by

Alan Goldfarb

August 16, 2006

The American Viticuture Area (AVA) system is in place to better define the more than 200 wine growing regions in North America, and has been in existence for little more than a quarter century. One would think that in that period of time, the consumer would have a better grasp of how those differentiations – if any – manifest themselves in the bottle.

Unfortunately, the AVA system as it exists in most places on the continent has frequently been utilized merely as a marketing tool, or as something that is little more than a reflection of existing geo-political boundaries. In other words, AVAs are mostly toothless, lacking discernable meaning or reality. In fact, many vintners don’t bother indicating on their labels the sub-region to which they might belong – particularly when their winery happens to be in a wider, more recognizable area with greater cachet, such as the Napa Valley.

However, if a small but vocal coalition of Napa Valley grape growers and vintners try hard enough, we may soon see more visible signs – literally – that will designate each of the 14 sub-appellations in the region.

The idea is to erect signage at the boundary lines of each of the valley’s sub-regions. The signs would inform visitors that there may exist differences in the bottle from one area to another; and that Napa Valley’s wines aren’t monolithic. The same group, incidentally, has also started a push to erect signs to point out various vineyards. A few of the AVAs do have signs already in place, but the group is calling for larger, more prominent placements.

Why, after 25 years, might the idea of widespread AVA signage take hold?

“The whole idea of terroir is that you have different climates of location which set you apart from anyone else. Otherwise, you might as well have stayed with Napa Valley (on your label),” concludes Davie Piña, a grower as well as a wine producer. “You also have classic vineyards like To Kalon (in Oakville), for example. This is a special micro-climate. Every vineyard owner would love to have their name on the label because it enhances the value and prestige of their vineyards.”

Currently, there are vineyard-designate laws pertaining to signage on the books in Napa County, but there are no such rules about AVA designations. So the group is beginning to lobby on two fronts. First, to get the county and all other interested parties to go along with the concept. Secondly, for permission to erect larger signs than the mandated 6-square-foot placards that are currently legal. (There are, of course, signs allowed at wineries to point out their presence.)

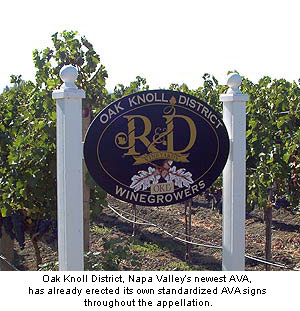

Doug Burnett, who owns a five-acre Cabernet vineyard in the Oak Knoll District, got the idea for a valley-wide campaign to erect AVA signs when he began putting up signs throughout Oak Knoll, the Napa Valley’s newest AVA.

“When I went through that process, it was a no-brainer to try and do the same for other AVAs,” he said. “The typical Napa visitor is a more sophisticated wine visitor than your average Safeway customer. They’re interested in defining different AVAs.”

So, Burnett began speaking to his colleagues and to county officials and eventually submitted a six-page proposal to the head of the Napa Valley Grape Growers Association.

Hillary Gittleman, the Napa County planning director acknowledged to Appellation America that she’s received “a couple of requests from different vintners who want to erect signs at major entry points to appellations.”

She said that each AVA would have – if approved – two signs that would indicate, “Welcome to …”

“We’ve had a couple of meetings and we’re trying to listen to their ideas,” Gittleman said. “But we’ve not gotten to the point of making a recommendation to the board of supervisors for a change. We’re at the preliminary, exploratory stage.”

Because the request is in its nascent stages, Jennifer Kopp, the executive director of the Growers Association, told Appellation America that “It doesn’t make sense for our organization to get involved at this time. We think it’s important but we’ll continue to monitor it. It’s at the level of the AVAs, not the vineyards and when it gets more specific, we’ll become more acquainted with it. When it gets to the vineyard level, that’s when we’ll step in.”

It’s also been learned that the Napa Valley Vintners – the marketing arm for most of the valley’s wineries – would want to have the words “Napa Valley” appear on all AVA and vineyard signs.

However, Napa Valley’s politics being as they are, we’re most likely looking at a long continuum before this issue becomes a fait accompli.

Gittleman, for one, has her concerns.

“The nice thing about it – it won’t be up to me. I can see both sides,” she said. “We’re certainly proud of our winemaking and appellations that exist. On the other hand, Napa Valley is such a beautiful place that we’ve been very restrictive. That’s why we don’t have sign pollution.”

Doug Burnett said his group is also concerned about “sign pollution.” That’s why he’s taking his request to everyone concerned, including organic farmers, who might want their particular niche recognized; and to the California Association of Wine Growers, which might be interested in furthering signage throughout the state.

Davie Piña thinks AVA prominence’s time has come.

“When this starts to occur in people with really good taste buds, you’re going to have other people follow,” he said.

So, why aren’t more wineries putting their sub-AVAs on their labels?

“More and more are doing it,” he said. “The Rutherford Dust Society has pushed this to the forefront. They’re looking at it for marketing and promotion. Others will start doing it that way, too.

“With the bigger wineries, they’re looking at different markets. They’re doing low-end wine. I don’t think anyone goes into a grocery looking for a Howell Mountain CK Mondavi. But Trinchero is doing it. They see the significance of (the sub-appellations), but they probably won’t do it with their other (Sutter Home) wines because it’s going to cloud the issue. Freddie Franzia (“Two Buck Chuck”) was the one who was clouding the issue.

“When you’re small, you try to get yourself known and go out and say you’re a Napa Valley wine,” Piña continued. “But when you say you’re a ‘Rutherford’ Cabernet, people pay attention. It gives you a boost to have sub-appellations on your label.”

Burnett, of course, concurs.

“We believe intuitively the customer is getting more sophisticated,”

Unfortunately, the AVA system as it exists in most places on the continent has frequently been utilized merely as a marketing tool, or as something that is little more than a reflection of existing geo-political boundaries. In other words, AVAs are mostly toothless, lacking discernable meaning or reality. In fact, many vintners don’t bother indicating on their labels the sub-region to which they might belong – particularly when their winery happens to be in a wider, more recognizable area with greater cachet, such as the Napa Valley.

However, if a small but vocal coalition of Napa Valley grape growers and vintners try hard enough, we may soon see more visible signs – literally – that will designate each of the 14 sub-appellations in the region.

The idea is to erect signage at the boundary lines of each of the valley’s sub-regions. The signs would inform visitors that there may exist differences in the bottle from one area to another; and that Napa Valley’s wines aren’t monolithic. The same group, incidentally, has also started a push to erect signs to point out various vineyards. A few of the AVAs do have signs already in place, but the group is calling for larger, more prominent placements.

Why, after 25 years, might the idea of widespread AVA signage take hold?

“The whole idea of terroir is that you have different climates of location which set you apart from anyone else. Otherwise, you might as well have stayed with Napa Valley (on your label),” concludes Davie Piña, a grower as well as a wine producer. “You also have classic vineyards like To Kalon (in Oakville), for example. This is a special micro-climate. Every vineyard owner would love to have their name on the label because it enhances the value and prestige of their vineyards.”

Currently, there are vineyard-designate laws pertaining to signage on the books in Napa County, but there are no such rules about AVA designations. So the group is beginning to lobby on two fronts. First, to get the county and all other interested parties to go along with the concept. Secondly, for permission to erect larger signs than the mandated 6-square-foot placards that are currently legal. (There are, of course, signs allowed at wineries to point out their presence.)

Doug Burnett, who owns a five-acre Cabernet vineyard in the Oak Knoll District, got the idea for a valley-wide campaign to erect AVA signs when he began putting up signs throughout Oak Knoll, the Napa Valley’s newest AVA.

“When I went through that process, it was a no-brainer to try and do the same for other AVAs,” he said. “The typical Napa visitor is a more sophisticated wine visitor than your average Safeway customer. They’re interested in defining different AVAs.”

So, Burnett began speaking to his colleagues and to county officials and eventually submitted a six-page proposal to the head of the Napa Valley Grape Growers Association.

Hillary Gittleman, the Napa County planning director acknowledged to Appellation America that she’s received “a couple of requests from different vintners who want to erect signs at major entry points to appellations.”

She said that each AVA would have – if approved – two signs that would indicate, “Welcome to …”

“We’ve had a couple of meetings and we’re trying to listen to their ideas,” Gittleman said. “But we’ve not gotten to the point of making a recommendation to the board of supervisors for a change. We’re at the preliminary, exploratory stage.”

Because the request is in its nascent stages, Jennifer Kopp, the executive director of the Growers Association, told Appellation America that “It doesn’t make sense for our organization to get involved at this time. We think it’s important but we’ll continue to monitor it. It’s at the level of the AVAs, not the vineyards and when it gets more specific, we’ll become more acquainted with it. When it gets to the vineyard level, that’s when we’ll step in.”

It’s also been learned that the Napa Valley Vintners – the marketing arm for most of the valley’s wineries – would want to have the words “Napa Valley” appear on all AVA and vineyard signs.

However, Napa Valley’s politics being as they are, we’re most likely looking at a long continuum before this issue becomes a fait accompli.

Gittleman, for one, has her concerns.

“The nice thing about it – it won’t be up to me. I can see both sides,” she said. “We’re certainly proud of our winemaking and appellations that exist. On the other hand, Napa Valley is such a beautiful place that we’ve been very restrictive. That’s why we don’t have sign pollution.”

Doug Burnett said his group is also concerned about “sign pollution.” That’s why he’s taking his request to everyone concerned, including organic farmers, who might want their particular niche recognized; and to the California Association of Wine Growers, which might be interested in furthering signage throughout the state.

Davie Piña thinks AVA prominence’s time has come.

“When this starts to occur in people with really good taste buds, you’re going to have other people follow,” he said.

So, why aren’t more wineries putting their sub-AVAs on their labels?

“More and more are doing it,” he said. “The Rutherford Dust Society has pushed this to the forefront. They’re looking at it for marketing and promotion. Others will start doing it that way, too.

“With the bigger wineries, they’re looking at different markets. They’re doing low-end wine. I don’t think anyone goes into a grocery looking for a Howell Mountain CK Mondavi. But Trinchero is doing it. They see the significance of (the sub-appellations), but they probably won’t do it with their other (Sutter Home) wines because it’s going to cloud the issue. Freddie Franzia (“Two Buck Chuck”) was the one who was clouding the issue.

“When you’re small, you try to get yourself known and go out and say you’re a Napa Valley wine,” Piña continued. “But when you say you’re a ‘Rutherford’ Cabernet, people pay attention. It gives you a boost to have sub-appellations on your label.”

Burnett, of course, concurs.

“We believe intuitively the customer is getting more sophisticated,”