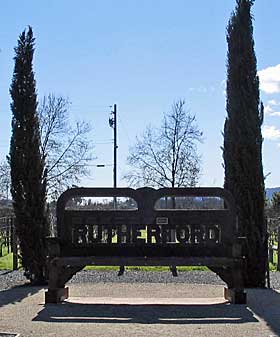

The Rutherford Bench in front of Franciscan Estate is the whimsical representation of the geological terrain in which Cabernet reigns.

Rutherford ~ Napa Valley (AVA)

The Rising Threat of Regional Transparency

A Rutherford Dust Society Cabernet tasting shows the appellation’s strengths…and weaknesses.

by

Dan Berger

August 28, 2007

T a recent tasting-evaluation of a range of Rutherford AVA Cabernet Sauvignons from the 2004 vintage, members of the media were treated to about 30 wines that were, for the most part, pretty good. If you can overlook the price for some of them (in the $70 to $125 range), you could make a good case for this being the pinnacle of recent Napa Valley Cabernets, for at least three reasons:

T a recent tasting-evaluation of a range of Rutherford AVA Cabernet Sauvignons from the 2004 vintage, members of the media were treated to about 30 wines that were, for the most part, pretty good. If you can overlook the price for some of them (in the $70 to $125 range), you could make a good case for this being the pinnacle of recent Napa Valley Cabernets, for at least three reasons:

1. 2004 was a good year, quality-wise, for Napa Valley red wines;

2. The number of producers who now make a Rutherford-designated Cabernet Sauvignon has grown, so the wine has taken on a critical mass, and,

3. Rutherford is the historic homeland for Cabernet in California, the place where Inglenook and Beaulieu were founded, where some of the greatest Cabs of the last 100 years were made, and where many of the nation’s finest wine makers have toiled.

And yet, as I went through all the wines in the allotted time, and listened to talk about the grape acreage of the area, I had a shocking realization: No one from Rutherford addressed the most obvious question, the one that would have made the tasting a complete circle of truth and meaningfulness: what is the essential character of a Rutherford Cabernet Sauvignon? They did say at one point that there was a similarity among the wines, but no one delineated what that similarity was. Indeed, I saw very little of the historic character once required for a wine to typify this area of the Cabernet world.

As Editor-At-Large for APPELLATION AMERICA, and as one of the senior members of the media at that tasting (my first visit to Rutherford as a journalist was 31 years ago), I could well have asked that question out loud. And I know for a certainty that what I would have been told, after a long, arduous discussion among the winery representatives, would have been totally unsatisfactory. I have as much background with these wines as anyone at that tasting and I know what the tenor of the area should be. And it wasn’t a component in most of the wines.

Only a tiny number of Rutherford Cabernets have anything remotely Rutherford-like

in their makeup any more.

The mere fact that such an obvious issue was not a part of the Rutherford Dust Society’s formal verbal discussion; that it was not a part of the classy printed materials we were given; and that no other media attendee even brought up the issue is either astounding proof that no one cares any more about regional character, or affirms that defining it, in terms that once were more in evidence, would be a ludicrous act since only a tiny number of Rutherford Cabernets have anything remotely Rutherford-like in their makeup any more.

in their makeup any more.

Indeed, if any wine maker did have a trace of the area’s terroir in his or her Cabernet Sauvignon, he or she would be derided as some sort of mastodon mired in the ooze of some prehistoric bog. The owner and wine maker would become pariahs in their own land, and soon (I’m sure) would fall prey to the score-mongering vultures who’d pick over their 78-point bones with a mockery reserved for those foolhardy enough to think they can change the course of destiny by making something with a classical bent.

The bottom line for most of the people who have so much wealth tied up in these precious soils is that survival (and the ticket to even greater wealth) means conformity to a style some producers may not personally like, but which sells better than the more structured wine of the past. And in my view, it means driving a 747 over the terroir characteristics of the wine and constructing a new model, one that is toothless and homogenous.

Napa Valley Style Multiple Choice: Myopia, Monotony, MonoTone, Monopoly

Indeed, as Randy Dunn of Dunn Vineyards ((Read Randy Dunn’s APPELLATION AMERICA interview) noted to me just two weeks after the “We [Napa Valley] are not only in danger of becoming a one-wine region, we’re in danger of making only one style of wine.”

~Randy Dunn, Dunn Vineyards

Rutherford Dust Society tasting, “We [Napa Valley] are not only in danger of becoming a one-wine region, we’re in danger of making only one style of wine.”

Not everyone is into this sort of global destruction of a birthright, of course. But the distinctive-ists really are from elsewhere. Think of the dozens of Russian River Valley Pinot Noir producers and the red wine makers along the California central coast, and in some pockets of Mendocino County. There is also Carneros Merlot, as well as Merlot from pockets in the Columbia Valley, and a handful of other tiny North American appellations (British Columbia’s Naramata Bench, Niagara, Oregon’s Umpqua and Rogue valleys; New York’s Finger Lakes; portions of Michigan, Ohio, and Virginia, to name just a few).

~Randy Dunn, Dunn Vineyards

But note if you will that these and other regions of the United States and Canada (and perhaps parts of Mexico’s Guadalupe Valley soon will be included here!) are anything but household words, and certainly are not on the lips of wine collectors as are the Cabernets of Oakville, Rutherford, Yountville, and soon Calistoga (see Alan Goldfarb’s excellent article on the latest in the Calistoga appellation fight). Moreover, few of these other-area wines sell for very much money, and in our star-aligned wine culture, a high price almost always equals success. When a wine sells for $30 or less, it is simply not taken seriously by some people.

So for the makers of one of the most famous wines from one of the most famous wine regions in American wine lore to pay no attention whatever to its own regional character (about which much was written 30 years ago) is a relinquishment of an essential component in the history of the region.

The late Andre Tchelistcheff defined the “Rutherford dust” elements inherent in a great Cabernet Sauvignon. They were elements that he said defined the region, just as the region defined the wine. The dried

With the Mayacamas Mountains as a backdrop, the valley floor of the Rutherford AVA is best known for its Cabernets with “Rutherford dust.”.

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,