The vineyards of Willamette Valley have produced noteworthy Pinots for decades but now they are gaining their well-deserved stardom.

The Willamette Valley

Pinot Noir Story

The producers of Willamette Pinot Noir have a 40-year track record and with new clones in the ground, and newly designated sub-appellations that they feel will transcend marketing stratagems, they are ready to face the future.

by

Alan Goldfarb

August 4, 2008

ain? What rain? Criss-crossing the two-lane country roads in the verdant northern Willamette Valley of Oregon at the very beginning of summer, I was awestruck by the beautiful weather. Not at all what I had expected.

ain? What rain? Criss-crossing the two-lane country roads in the verdant northern Willamette Valley of Oregon at the very beginning of summer, I was awestruck by the beautiful weather. Not at all what I had expected.

The Great Precipitation of the Willamette was about all that my esteemed colleague Lettie Teague could talk about in her Food & Wine Magazine article when she visited last March. Three months later, I, too, was looking for the infamous rains that pelt this Pinot Noir-producing region every year. But from what I got – four days of sunny temperatures ranging from the high 70s to the high 80s – I made the conclusion, like so many before me, that some of the best

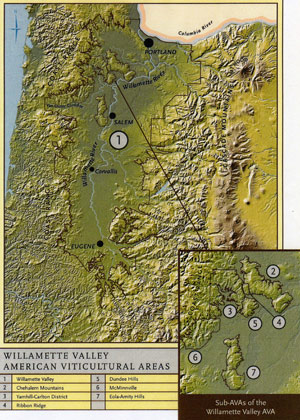

This map, courtesy of Anne Amie Vineyards, shows Willamette Valley and its sub-AVAs in relation to their location in Oregon.

(Click map to enlarge.)

As I traipsed over the Willamette (pronounced wil LAM ett) visiting about 10 producers, the agreeable weather was always the first topic of conversation. The warmth, without much humidity, was a welcome relief after a nasty, cold, wet winter and spring, which has set back the growing season about three weeks. It gave pause, I’m sure, to those winemakers who are not used to such early warm and dry conditions. It could be a harbinger of things yet to come as they – to a person – seemed keenly aware of the real possibility of climate change.

The increasing caprice of the weather is just one more factor for these Oregonians to consider. In the last decade, Oregon producers began to realize that many of the clones they were instructed to utilize, mostly from UC Davis in California, were of the wrong material for their area.

Now, after more than four decades, the producers of Willamette Pinot Noir have garnered a track record to be reckoned with. They face the future with new clones in the ground, and newly designated sub-appellations that they feel will transcend marketing stratagems.

Yes, that’s right, with exceptions such as Pinot Gris, Pinot Blanc, and Chardonnay – cool climate varieties all – it’s Pinot Noir that will surely be the horse that the Willamette Valley will ride. Unless, of course, climate change becomes an unequivocal reality. (Toward that end, several of the producers I met have hedged their bets by beginning to plant Syrah.)

The Willamette – running 150 miles long and 60 miles wide – is located about an hour southwest of Portland. It is the largest American Viticultural Area (AVA) in the state with about 200 wineries and 10,000 acres planted, which produce about 60 percent of Oregon’s wines. However, unlike the Napa Valley, where vineyards can be seen just about everywhere, Willamette’s vineyards are interspersed throughout the region, hidden in plain site in the nooks and crannies of the low-lying green, tree-dotted hills.

That’s because, unlike many wine-growing regions in California, Willamette vineyards seem more well suited to their sites. This is partially a result of the fragility of Pinot itself, and also to protect the vines from the weather (annual rainfall is between 45-to-60 inches as compared to the Anderson Valley’s (Mendocino) 60-inch average and Burgundy (28 inches).

Pat Campbell, co-founder of Elk Cove Vineyards

As Shirley Brooks of Elk Cove Vineyards (founded in '74, thus one the oldest of Oregon’s producers) tells me, “Some (more) Pinot Noir will be planted on the valley floor … but that’s not the best vineyard land.” At Elk Cove, which is in the Yamhill-Carlton sub-region, she says, “We’ve planted seeds of the future for hillside (vineyards).”

Thomas Houseman of Anne Amie Vineyards

“I was looking for a way to express myself,” he says as he explains why he left the state south of the border to come here. He is insistent in not using clones for his Pinot that are often used in California, which he likens to the “mockumentary” Spinal Tap, and which cause those wines to “crank it up to 11”.

Oregon Pinots he says are not jammy. He characterizes some of them as “sappy”. “And we need to get away from sappy and become more lifted and elegant,” Houseman declares.

On balance, a preponderance of the 40 or so Willamette Valley Pinot Noirs I tasted during my visit were neither jammy nor sappy. Most were elegant, with wonderful bright fruit, and in balance, with decided levels of acidity and relatively reasonable alcohol averaging around 14 percent.

With few exceptions, they were not California-like, although you could make a comparison to the Anderson Valley and to the Carneros. They were nearly all not Burgundian. Rather, they were Oregon, Willamette Valley Pinot Noirs.

The 2005 Anam Cara Nicolas Vineyard (about $40), comes from a very small producer , like many of the Willamette’s producers. It has incredible fruit and spot-on balance with a substantial body for long-term ageing. From the Chehalem Mountains, which are the nearest vineyards to Portland, the stated alcohol is 13.7 percent.

Over at WillaKenzie Estates, vineyard manager Daniel Fey is stumped when I ask what a typical year is like in the Yamhill-Carlton region in which his vineyards reside. He answers simply: “I haven’t had any.”

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,