While Larkmead Vineyards has mostly newer plantings, some vines, like these Tocai Friulano, are more than a century old and produce terroir-driven grapes coveted by other wineries.

Old, historical Larkmead Vineyard:

The vines may be young,

but the terroir isn’t

by

Alan Goldfarb

September 22, 2008

Is an old vineyard – one of the oldest parcels of land in California – still an old vineyard even if a great preponderance of the grape vines that grow on it are no more than 23 years old?

One could further ask: Even though wine grapes have been grown on this plot of land for the last 120 years, give or take, does that mean that the wines made from it now have that something special that separates it from much younger vineyards?

Jeff Morgan, who gets the Cabernet Sauvignon for his $90 kosher wine, Covenant, from the historic Larkmead Vineyards south of Calistoga, naturally believes the answer to both questions is in the affirmative.

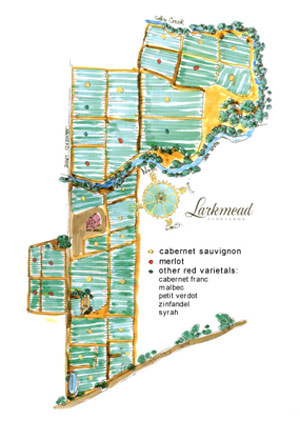

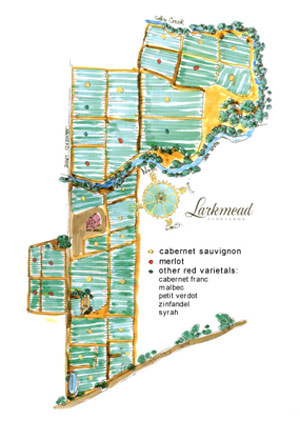

Howgreen old is my valley – a map of Larkmead”s century old vineyards.“I think it’s a very distinctive spot. The grapes I’ve tasted out of this vineyard have an expression of terroir. They planted the vineyard in 1889 [You read that right: 1889] when there wasn’t a whole lot planted in the Napa Valley, so I figured it was good then, it still has got to be pretty good,” Morgan proclaims, emphatically

As for the question of relatively new vines (the average age is 11-13 years) planted in aged ground, Morgan is just as effusive: “Vines evolve, but the terroir doesn’t change, at least not over the course of our lifetime.”

Climate change notwithstanding, Morgan gets his Cab from a three-acre portion of the vineyard from vines that are 13 to 15 years old. It was recommended to him by Dave Ramey, who was then the winemaker at Rudd Vineyards, whose owner, Leslie Rudd, is a partner in Covenant.

According to Morgan, who has been using the fruit from Larkmead for five years (10 percent goes into his other label, RED C), Ramey told him, “This is a good spot. There’s something special going on here.” That “special” spot is rocky and manifests in small clusters and large berries and translates to the bottle in soft tannins and, says, Morgan, licorice and herb flavors.

Those characteristics would suggest hillside fruit, which is how Larkmead’s assistant winemaker Dan Petroski describes Larkmead’s grapes. It’s in the narrowest part of the Napa Valley, south of Calistoga and north of St. Helena. The 113-acre vineyard, which runs north to south, comes up to the eastern bench underneath Howell Mountain.

Larkmead Vineyards owner Cameron Baker.The vineyard is divided into five discernible blocks planted mostly to Cabernet and Merlot. In addition to Larkmead’s own recently ramped up production, which produces about 9,000 cases, the highly coveted and expensive fruit goes to Cakebread, Merryvale, Duckhorn (which is next door), Garric, and, of course, to Covenant. Zinfandel goes to Orin Swift’s The Prisoner.

Some of those blocks are on loamy concentrated sand, clay, and silt, the latter of which heads toward the Napa River. There are more gravelly soils as one heads toward Highway 29.

Petroski unflinchingly describes this portion as being “similar to left bank Bordeaux in Graves.” In other spots – as in Jeff Morgan’s portion - there are large cobbles and pebbles, which indicate that the river or Ritchie Creek once went through the property.

Petroski characterizes some of the Cabernet as having red aromatics similar to intense, bright, textured fruit, with mineral, powdery and dusty qualities “that come from gravelly soils similar to Howell Mountain, that are uncharacteristic to valley-floor fruit. “Larkmead terroir is very noticeable and distinguishable,” he concludes. Additionally, he says the clay soils in another block are “similar to the right bank” of Bordeaux. Thus, there’s Merlot planted there.

two white varieties the vineyard yields, the Italian grape, Tocai Friulano. With less than 800 vines, it is the oldest part of the vineyard, with anecdotal evidence that says it was first planted in 1889.

two white varieties the vineyard yields, the Italian grape, Tocai Friulano. With less than 800 vines, it is the oldest part of the vineyard, with anecdotal evidence that says it was first planted in 1889.

Larkmead produces less than 150 cases a year of the northeastern Italian varietal. It is one of the few Tocai’s coming out of California, and what a wine it is: Rich, lush and thick with a green-tinged color, the wine displays the minerality that Petroski describes. At $28, it comes as close to a Friuli Tocai as is imaginable. Chappellet Vineyards on Pritchard Hill first took the Tocai in the ‘90s, but now Larkmead keeps it for itself under an invigorated program to revive the label that first produced wine in the late 19th century.

Owner Cameron Baker embarked on a complete new regimen in 1994, replanting the vineyard and building a winery. Why replant such old and cherished vines? “The early 1990s was not a very favorable economic climate for grapes. We wanted to reestablish Larkmead to the preeminence that we once had. We had 45 acres in whites and older Cabernet that were virused,” pragmatically answers Cameron Baker,

Cameron Baker and assistant winemaker Dan Petroski check up on the Tocai Friulano vines a few weeks before harvest.whose wife’s family purchased the property in 1948. “It’s always been an historic site which produced world-class grapes, and there are those that say it’s one of the best sites in the Napa Valley.”

Indeed, the pedigree can be substantiated. In “Bottled Poetry” by James Lapsley, Andre Tchelistcheff, one of the pioneers who resurrected the Napa Valley in the years following Prohibition after arriving in 1938, recalled four “outstanding” wineries, “Inglenook, Beaulieu (for whom he worked), Larkmead and Beringer.”

According to Baker, the clones for Araujo’s Eisele Vineyard came from Larkmead, as did Warren Winiarski’s (Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars) first vineyard which was on Howell Mountain. Dr. James Olmo of UC Davis got clones from Larkmead that were used for the university’s Oakville testing station.

“Yes, we do believe we have soils that are world-class and we do our best to be true to the vineyard,” says Dan Petroski. Adds Baker, “If the site weren’t this great, we wouldn’t have done this,” referring to the replanting program. “The site allows us to make world-class wines whether they (the vines) are 3 years old, 5 years old or 100. “We have a definite micro-climate here … (So) it’s the terroir.”

Photos courtesy of Larkmead Vineyard

One could further ask: Even though wine grapes have been grown on this plot of land for the last 120 years, give or take, does that mean that the wines made from it now have that something special that separates it from much younger vineyards?

Jeff Morgan, who gets the Cabernet Sauvignon for his $90 kosher wine, Covenant, from the historic Larkmead Vineyards south of Calistoga, naturally believes the answer to both questions is in the affirmative.

How

As for the question of relatively new vines (the average age is 11-13 years) planted in aged ground, Morgan is just as effusive: “Vines evolve, but the terroir doesn’t change, at least not over the course of our lifetime.”

Climate change notwithstanding, Morgan gets his Cab from a three-acre portion of the vineyard from vines that are 13 to 15 years old. It was recommended to him by Dave Ramey, who was then the winemaker at Rudd Vineyards, whose owner, Leslie Rudd, is a partner in Covenant.

According to Morgan, who has been using the fruit from Larkmead for five years (10 percent goes into his other label, RED C), Ramey told him, “This is a good spot. There’s something special going on here.” That “special” spot is rocky and manifests in small clusters and large berries and translates to the bottle in soft tannins and, says, Morgan, licorice and herb flavors.

Those characteristics would suggest hillside fruit, which is how Larkmead’s assistant winemaker Dan Petroski describes Larkmead’s grapes. It’s in the narrowest part of the Napa Valley, south of Calistoga and north of St. Helena. The 113-acre vineyard, which runs north to south, comes up to the eastern bench underneath Howell Mountain.

Larkmead Vineyards owner Cameron Baker.

Some of those blocks are on loamy concentrated sand, clay, and silt, the latter of which heads toward the Napa River. There are more gravelly soils as one heads toward Highway 29.

Petroski unflinchingly describes this portion as being “similar to left bank Bordeaux in Graves.” In other spots – as in Jeff Morgan’s portion - there are large cobbles and pebbles, which indicate that the river or Ritchie Creek once went through the property.

Petroski characterizes some of the Cabernet as having red aromatics similar to intense, bright, textured fruit, with mineral, powdery and dusty qualities “that come from gravelly soils similar to Howell Mountain, that are uncharacteristic to valley-floor fruit. “Larkmead terroir is very noticeable and distinguishable,” he concludes. Additionally, he says the clay soils in another block are “similar to the right bank” of Bordeaux. Thus, there’s Merlot planted there.

Back into the Future with Tocai Friulano

Yet another block features darker, brooding fruit, which led Larkmead’s winemaker Andy Smith to proclaim the vineyard to be “one of the most diverse single vineyards in Napa or Sonoma.” That diversity can be seen in one of the two white varieties the vineyard yields, the Italian grape, Tocai Friulano. With less than 800 vines, it is the oldest part of the vineyard, with anecdotal evidence that says it was first planted in 1889.

two white varieties the vineyard yields, the Italian grape, Tocai Friulano. With less than 800 vines, it is the oldest part of the vineyard, with anecdotal evidence that says it was first planted in 1889.

Larkmead produces less than 150 cases a year of the northeastern Italian varietal. It is one of the few Tocai’s coming out of California, and what a wine it is: Rich, lush and thick with a green-tinged color, the wine displays the minerality that Petroski describes. At $28, it comes as close to a Friuli Tocai as is imaginable. Chappellet Vineyards on Pritchard Hill first took the Tocai in the ‘90s, but now Larkmead keeps it for itself under an invigorated program to revive the label that first produced wine in the late 19th century.

Owner Cameron Baker embarked on a complete new regimen in 1994, replanting the vineyard and building a winery. Why replant such old and cherished vines? “The early 1990s was not a very favorable economic climate for grapes. We wanted to reestablish Larkmead to the preeminence that we once had. We had 45 acres in whites and older Cabernet that were virused,” pragmatically answers Cameron Baker,

Cameron Baker and assistant winemaker Dan Petroski check up on the Tocai Friulano vines a few weeks before harvest.

Indeed, the pedigree can be substantiated. In “Bottled Poetry” by James Lapsley, Andre Tchelistcheff, one of the pioneers who resurrected the Napa Valley in the years following Prohibition after arriving in 1938, recalled four “outstanding” wineries, “Inglenook, Beaulieu (for whom he worked), Larkmead and Beringer.”

According to Baker, the clones for Araujo’s Eisele Vineyard came from Larkmead, as did Warren Winiarski’s (Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars) first vineyard which was on Howell Mountain. Dr. James Olmo of UC Davis got clones from Larkmead that were used for the university’s Oakville testing station.

“Yes, we do believe we have soils that are world-class and we do our best to be true to the vineyard,” says Dan Petroski. Adds Baker, “If the site weren’t this great, we wouldn’t have done this,” referring to the replanting program. “The site allows us to make world-class wines whether they (the vines) are 3 years old, 5 years old or 100. “We have a definite micro-climate here … (So) it’s the terroir.”

Photos courtesy of Larkmead Vineyard

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,