Appellation delineation in Oregon has allowed winemakers to work in small groups to promote the distinctiveness of their individual regions.

Defining the Regional Characteristics of Oregon Pinot Noir: An Interview with Ken Wright

"(An) AVA (American Viticulture Area) is only valuable if it has been well drawn and the wines from the delimited area share traits in quality, aroma, flavor and texture"

by

Rebecca Murphy

October 3, 2006

Ken Wright, owner and winemaker of Ken Wright Cellars, Carlton, OR was involved in the process of creating the sub-AVAs of the Willamette Valley. He drew the original proposed maps for the sub AVAs and also wrote the application for the Yamhill-Carlton District AVA. I met with Ken recently to hear about his experiences in this process.

Ken Wright has strong opinions about the meaning of an AVA. He believes that an AVA is only valuable if it has been well drawn and the wines from the delimited area share traits in quality, aroma, flavor and texture. “If the wines coming from the region as a whole don’t share these qualities, then the AVA in the end becomes another set of labeling information on the bottle that is really only marketing,” Ken declared. His ideal is to define the area in such a way that a consumer can buy a wine made by an unfamiliar producer from a familiar AVA and have some sense of what to expect. “That’s what an AVA, to me, ought to be about,” he said.

Ken Wright has strong opinions about the meaning of an AVA. He believes that an AVA is only valuable if it has been well drawn and the wines from the delimited area share traits in quality, aroma, flavor and texture. “If the wines coming from the region as a whole don’t share these qualities, then the AVA in the end becomes another set of labeling information on the bottle that is really only marketing,” Ken declared. His ideal is to define the area in such a way that a consumer can buy a wine made by an unfamiliar producer from a familiar AVA and have some sense of what to expect. “That’s what an AVA, to me, ought to be about,” he said.

Wright explained that in 1995, an initial attempt was made to develop sub-AVAs in the Willamette Valley. “Dick Shea (Shea Vineyards and Shea Wine Cellars, Yamhill-Carlton District AVA), Doug Tunnell (Brick House Vineyards, Ribbon Ridge AVA), John Thomas (Acme Wineworks, Yamhill-Carlton AVA) and I got together and asked the industry to look at the potential of describing new viticultural areas. It was a good meeting and well attended by almost everybody who was a mover and shaker at the time. The upshot was that the industry as a whole was not ready to move forward on the AVAs, for two main reasons.

“One was that a number of people simply did not recognize that there were different regions. They didn’t believe that they could assign particular qualities to the different regions.” Wright explained that many vintners at the time either did not work with grapes from different regions, or did not vinify grapes from different regions separately. “At that time, even though it doesn’t seem that long ago, there were very few vineyard-designated wines. Therefore, there was little opportunity to try a wine from a particular site,” he said. Since wines were often blends from a number of regions, winemakers “were not sourcing enough fruit from various areas to have a sense of what the areas were all about. They also didn’t work with grapes in a way that kept them separate in the process so they couldn’t get to know what those qualities could be. There was just a lack of experience.”

The other concern was about creating divisiveness within the industry. “When you start to draw a line, someone is on one side and someone is on the other.” Wright explained that there has always been an incredibly cooperative spirit in the Oregon industry, so “there was a real concern that if we started drawing lines that might break down that spirit of cooperation. And that was a fair concern. I thought the benefits out weighed those concerns, but those concerns won the day.”

It took someone new to revive the issue. And that someone was Alex Sokol Blosser (Sokol Blosser Winery, Dundee Hills AVA), whose parents were part of the early arrivals to the Willamette Valley, planting their first vines in 1971. Since Alex only joined the family business in 1998, he was not part of the initial meeting to discuss potential AVAs, but he was interested in re-addressing the idea.

“So we got together at Sokol Blosser and, as it turned out, the timing was right,” said Wright. Though there were still concerns about divisiveness, in the intervening years there had been an explosion of vineyard-designated wines. “For me, that’s what we do (at Ken Wright Cellars) and what I love, but a lot of people began making vineyard-designated wines in the interim and that was tremendous information for the industry. All of a sudden, all the winemakers and growers were able to try these wines from particular locations all over the valley. Often they had the opportunity to try a number of wines from one site but made by different producers and they could see the thread of consistency in those wines. It convinced a lot of people that, yes, there were real regions and they saw the regional aspect that we had originally presented.”

“So we got together at Sokol Blosser and, as it turned out, the timing was right,” said Wright. Though there were still concerns about divisiveness, in the intervening years there had been an explosion of vineyard-designated wines. “For me, that’s what we do (at Ken Wright Cellars) and what I love, but a lot of people began making vineyard-designated wines in the interim and that was tremendous information for the industry. All of a sudden, all the winemakers and growers were able to try these wines from particular locations all over the valley. Often they had the opportunity to try a number of wines from one site but made by different producers and they could see the thread of consistency in those wines. It convinced a lot of people that, yes, there were real regions and they saw the regional aspect that we had originally presented.”

For some people another reason to go forward was the sense that the industry was about to explode. New investment, new wineries and new growers were popping up all over the Willamette Valley, and “now would be easier than any day beyond now. The longer we waited, the more people there would be and the more difficult the process would be,” Wright explained.

Wright noted that “the way I had the maps drawn was different than how they came out. My maps were drawn purely on soil. Period. And they were based on parent material. Because, in my mind, the parent material was the ultimate influence on the qualities of Pinot Noir. In our area, the soils are very simple, composed of either marine sediment or basalts, and there are a few areas of loess (soil material deposited by wind). That’s important because those two parent materials produce vastly different qualities in Pinot Noir. To me, they end up having more influence on the way Pinot Noir tastes and smells and feels than anything the winemaker can possibly do. Our soil types are very basic and not very complex. The wine produced from them is very complex. So, the soil is the greatest influence there is on the quality of Pinot Noir grown here.”

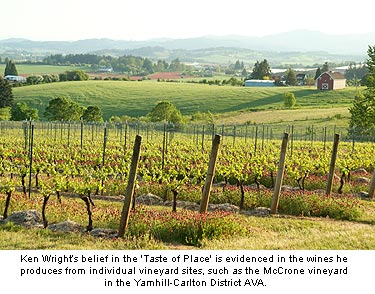

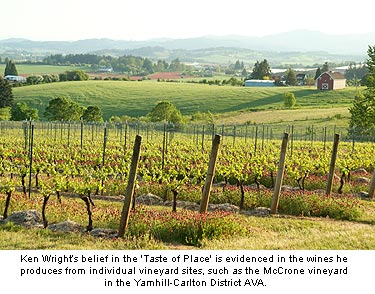

Wright drew the original proposed AVA maps according to where the basalt parent material and marine sediments were located, “because what I found over many, many years is that basalt soils tend to produce Pinot Noirs that are fruit driven. Whether it’s red, blue, or black, it’s all about fruit, both in aroma and flavor. Where as the sedimentary soils tend to produce wines that have a lot of floral and spice qualities. So, in Pinot Noirs from Ribbon Ridge and Yamhill-Carlton, you’ll see a lot of lavender, cola, tobacco, cedar, anise, and violets and other qualities that are not fruit based. It isn’t that they are more complex -- they’re just different. I make wines from all the areas, and we love the differences. We celebrate them. The ability of Pinot to be a vehicle to supply that sense of place is phenomenal. No variety touches it. Riesling tries, but it doesn’t.

The thing that drove the original interest in 1995 was a love of the quality of the grape to be able to describe a place in such detail, to connect people to a specific location. Not simply to identify an overall geographic region. It was really a desire to connect people to areas that had similar qualities. That was the original purpose anyway.”

The AVA process proceeded with a captain assigned to each proposed region to facilitate. These captains “took those maps to their constituency, whi

Ken Wright has strong opinions about the meaning of an AVA. He believes that an AVA is only valuable if it has been well drawn and the wines from the delimited area share traits in quality, aroma, flavor and texture. “If the wines coming from the region as a whole don’t share these qualities, then the AVA in the end becomes another set of labeling information on the bottle that is really only marketing,” Ken declared. His ideal is to define the area in such a way that a consumer can buy a wine made by an unfamiliar producer from a familiar AVA and have some sense of what to expect. “That’s what an AVA, to me, ought to be about,” he said.

Ken Wright has strong opinions about the meaning of an AVA. He believes that an AVA is only valuable if it has been well drawn and the wines from the delimited area share traits in quality, aroma, flavor and texture. “If the wines coming from the region as a whole don’t share these qualities, then the AVA in the end becomes another set of labeling information on the bottle that is really only marketing,” Ken declared. His ideal is to define the area in such a way that a consumer can buy a wine made by an unfamiliar producer from a familiar AVA and have some sense of what to expect. “That’s what an AVA, to me, ought to be about,” he said. Wright explained that in 1995, an initial attempt was made to develop sub-AVAs in the Willamette Valley. “Dick Shea (Shea Vineyards and Shea Wine Cellars, Yamhill-Carlton District AVA), Doug Tunnell (Brick House Vineyards, Ribbon Ridge AVA), John Thomas (Acme Wineworks, Yamhill-Carlton AVA) and I got together and asked the industry to look at the potential of describing new viticultural areas. It was a good meeting and well attended by almost everybody who was a mover and shaker at the time. The upshot was that the industry as a whole was not ready to move forward on the AVAs, for two main reasons.

“One was that a number of people simply did not recognize that there were different regions. They didn’t believe that they could assign particular qualities to the different regions.” Wright explained that many vintners at the time either did not work with grapes from different regions, or did not vinify grapes from different regions separately. “At that time, even though it doesn’t seem that long ago, there were very few vineyard-designated wines. Therefore, there was little opportunity to try a wine from a particular site,” he said. Since wines were often blends from a number of regions, winemakers “were not sourcing enough fruit from various areas to have a sense of what the areas were all about. They also didn’t work with grapes in a way that kept them separate in the process so they couldn’t get to know what those qualities could be. There was just a lack of experience.”

The other concern was about creating divisiveness within the industry. “When you start to draw a line, someone is on one side and someone is on the other.” Wright explained that there has always been an incredibly cooperative spirit in the Oregon industry, so “there was a real concern that if we started drawing lines that might break down that spirit of cooperation. And that was a fair concern. I thought the benefits out weighed those concerns, but those concerns won the day.”

It took someone new to revive the issue. And that someone was Alex Sokol Blosser (Sokol Blosser Winery, Dundee Hills AVA), whose parents were part of the early arrivals to the Willamette Valley, planting their first vines in 1971. Since Alex only joined the family business in 1998, he was not part of the initial meeting to discuss potential AVAs, but he was interested in re-addressing the idea.

“So we got together at Sokol Blosser and, as it turned out, the timing was right,” said Wright. Though there were still concerns about divisiveness, in the intervening years there had been an explosion of vineyard-designated wines. “For me, that’s what we do (at Ken Wright Cellars) and what I love, but a lot of people began making vineyard-designated wines in the interim and that was tremendous information for the industry. All of a sudden, all the winemakers and growers were able to try these wines from particular locations all over the valley. Often they had the opportunity to try a number of wines from one site but made by different producers and they could see the thread of consistency in those wines. It convinced a lot of people that, yes, there were real regions and they saw the regional aspect that we had originally presented.”

“So we got together at Sokol Blosser and, as it turned out, the timing was right,” said Wright. Though there were still concerns about divisiveness, in the intervening years there had been an explosion of vineyard-designated wines. “For me, that’s what we do (at Ken Wright Cellars) and what I love, but a lot of people began making vineyard-designated wines in the interim and that was tremendous information for the industry. All of a sudden, all the winemakers and growers were able to try these wines from particular locations all over the valley. Often they had the opportunity to try a number of wines from one site but made by different producers and they could see the thread of consistency in those wines. It convinced a lot of people that, yes, there were real regions and they saw the regional aspect that we had originally presented.” For some people another reason to go forward was the sense that the industry was about to explode. New investment, new wineries and new growers were popping up all over the Willamette Valley, and “now would be easier than any day beyond now. The longer we waited, the more people there would be and the more difficult the process would be,” Wright explained.

Wright noted that “the way I had the maps drawn was different than how they came out. My maps were drawn purely on soil. Period. And they were based on parent material. Because, in my mind, the parent material was the ultimate influence on the qualities of Pinot Noir. In our area, the soils are very simple, composed of either marine sediment or basalts, and there are a few areas of loess (soil material deposited by wind). That’s important because those two parent materials produce vastly different qualities in Pinot Noir. To me, they end up having more influence on the way Pinot Noir tastes and smells and feels than anything the winemaker can possibly do. Our soil types are very basic and not very complex. The wine produced from them is very complex. So, the soil is the greatest influence there is on the quality of Pinot Noir grown here.”

Wright drew the original proposed AVA maps according to where the basalt parent material and marine sediments were located, “because what I found over many, many years is that basalt soils tend to produce Pinot Noirs that are fruit driven. Whether it’s red, blue, or black, it’s all about fruit, both in aroma and flavor. Where as the sedimentary soils tend to produce wines that have a lot of floral and spice qualities. So, in Pinot Noirs from Ribbon Ridge and Yamhill-Carlton, you’ll see a lot of lavender, cola, tobacco, cedar, anise, and violets and other qualities that are not fruit based. It isn’t that they are more complex -- they’re just different. I make wines from all the areas, and we love the differences. We celebrate them. The ability of Pinot to be a vehicle to supply that sense of place is phenomenal. No variety touches it. Riesling tries, but it doesn’t.

The thing that drove the original interest in 1995 was a love of the quality of the grape to be able to describe a place in such detail, to connect people to a specific location. Not simply to identify an overall geographic region. It was really a desire to connect people to areas that had similar qualities. That was the original purpose anyway.”

The AVA process proceeded with a captain assigned to each proposed region to facilitate. These captains “took those maps to their constituency, whi