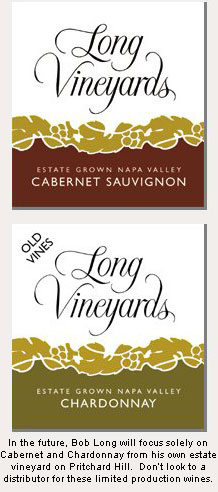

The hope for terroir driven wines is for small producers is to find a way to circumvent distributors -- whose interest is the commoditization of wine -- and sell directly to consumers.

Terroir in the Face of the American Marketing Machine: An Interview with Bob Long

"Big, cooperative wineries aren’t interested in terroir. Small producers will usually be craftsmen, ‘terroirists’ first."

by

Alan Goldfarb

September 22, 2006

Alan Goldfarb (AG): Tell us about Pritchard Hill. Will it ever become an AVA?

Bob Long (BL): Pritchard Hill is a de facto appellation. Nobody knows who’s there and what they produce.

I think it divides along two lines: The first is “Pritchard Hill proper” that goes from the culvert on Highway 128, which is a creek that spills into Lake Hennessey. There you’ll find Long, David Arthur, Pires, Greg Melanson (a grower), Gordon Anderson (a grower for Chappellet), Harrison, Bryant, Chappellet and to the east and farther up, Cloud View, and Versant.

Then there’s a dividing point in a canyon up the hill above Oakville where there is Krupp Brothers (Stagecoach Vineyards), Nelson (a grower), Colgin, Martinez (a grower), Miner Family Vineyards, and Neyers.

AG: Has there been discussion about forming an AVA?

BL: The Chappellets own the name of Pritchard Hill. Over the years there have been discussions. But that problem would go away if we simply called it “Lake Hennessey.”

AG: But Pritchard Hill has so much more cachet.

BL: Yes it does. So, it’s the sort of thing that might never get done.

AG: Has anyone approached the Chappellets?

BL: Oh, yes, the Chappellets have initiated it (the talks). There’s no controversy, just how do you organize it? There’s a weak association because not many live up here full-time.

AG: So, how should Pritchard Hill be defined?

BL: In the purest sense … the idea would be to establish Pritchard Hill as a narrowly based geographic thing and then build the terroir.

What we have is a very strong commitment to Cabernet, and a little bit of Syrah. It could be enough to get your arms around from a grape growing and winemaking standpoint.

(But) I’m in favor of having a Lake Hennessey AVA, which would include Anderson’s Conn Valley and Kuleto, and anybody that has drainage into the basin of Lake Hennessey. From a marketing point of view, and staying away from terroir, this would make a lot of sense.

AG: What are the differences among the various sites on Pritchard Hill and the larger Lake Hennessey region you propose?

BL: I’m not sure if there are substantial differences between Cabernet grown near Lake Hennessey or between Colgin, David Arthur or Stagecoach because the growing conditions – rainfall and soils – are similar. Pritchard Hill faces northwest, so there’s a significant difference in temperatures.

On the Kuleto side – across the canyon – on the top, there’s a good chance that the soil profiles and the weather are different. I have a feeling that the soil depth is different.

On the Conn Valley side, some of the soils are alluvial. There’s tufa. And the exposure is more toward the southwest.

If we’re going to embrace the marketing aspect of it, the more broad-based the appellation is, the more interesting it is for consumers, because it’s clear that the appellations have become more about marketing than grape growing.

AG: That brings us to your thoughts on terroir and the AVA system in general.

BL: You had to be an idealist to start in the wine business in the ‘60s. All of our early investigations relied heavily on examination of what went on in Europe. All of us, in the beginning and continuing, looked long and hard at what the French were doing.

Having said that, in an ideal way, I think it would be better if we did the same thing as the French. If we developed single vineyards it would be very clear to consumers what we’re about.

However, ideals will only get you so far. The American wine business is a clear example of capitalism. Our vineyards were not established by potentates and kings. We have developed a model of a winery that has to do with the winery business and increasing the value of it.

What we have is an American wine industry that has goals and the objective is to see those grow. And that necessarily means the whole winemaking culture – rather than focusing on vineyard awareness, which tends to be labor intensive – needs to acquire more land, more vineyards, and to develop blended wines. The idea is to create the image of the winery that has its place in PR and advertising, then to try and convince people of its availability, and to make those winery products attractive. It’s more like the way people sell clothes or cars, rather than terroir. It’s classic American marketing.

AG: At the expense of terroir?

BL: There are two problems with the terroir concept, which is the traditional French way. First, nobody is looking at it here. There isn’t a systematic investigation of what the wines are like and how they’re grown. It happens only randomly.

BL: There are two problems with the terroir concept, which is the traditional French way. First, nobody is looking at it here. There isn’t a systematic investigation of what the wines are like and how they’re grown. It happens only randomly.

The second problem is the urgency to sell things. It results in homogenization. The focus, the attention of the consumer, is being drawn somewhere else. Terroir to me is the soils and the way the grapes are expressed. Terroir is not winemaking. But that’s a very narrow view.

Homogenization and commoditization of wine does not emphasize small-production wines from specific areas. We’re training the American taste to enjoy Chardonnay, and Pinot Noir. We have a very difficult time reaching out to Americans, getting them interested in these types of (terroir expressive) wines.

Consolidation is driving the interest of the distributors because they don’t want to talk to anyone unless you have 100,000 cases. What that means is that the taste of American wines is limited to these wines.

It has not only chased away the development of better quality wines but it has discouraged people from trying different things. In the restaurant-culture, sommeliers don’t have the purchasing power, but they’re certainly keeping it alive.

It’s a question of personal experience versus the environment in which they live. It’s clear that it is the younger people who are buying these wines. They like

Bob Long (BL): Pritchard Hill is a de facto appellation. Nobody knows who’s there and what they produce.

I think it divides along two lines: The first is “Pritchard Hill proper” that goes from the culvert on Highway 128, which is a creek that spills into Lake Hennessey. There you’ll find Long, David Arthur, Pires, Greg Melanson (a grower), Gordon Anderson (a grower for Chappellet), Harrison, Bryant, Chappellet and to the east and farther up, Cloud View, and Versant.

Then there’s a dividing point in a canyon up the hill above Oakville where there is Krupp Brothers (Stagecoach Vineyards), Nelson (a grower), Colgin, Martinez (a grower), Miner Family Vineyards, and Neyers.

AG: Has there been discussion about forming an AVA?

BL: The Chappellets own the name of Pritchard Hill. Over the years there have been discussions. But that problem would go away if we simply called it “Lake Hennessey.”

AG: But Pritchard Hill has so much more cachet.

BL: Yes it does. So, it’s the sort of thing that might never get done.

AG: Has anyone approached the Chappellets?

BL: Oh, yes, the Chappellets have initiated it (the talks). There’s no controversy, just how do you organize it? There’s a weak association because not many live up here full-time.

AG: So, how should Pritchard Hill be defined?

BL: In the purest sense … the idea would be to establish Pritchard Hill as a narrowly based geographic thing and then build the terroir.

What we have is a very strong commitment to Cabernet, and a little bit of Syrah. It could be enough to get your arms around from a grape growing and winemaking standpoint.

(But) I’m in favor of having a Lake Hennessey AVA, which would include Anderson’s Conn Valley and Kuleto, and anybody that has drainage into the basin of Lake Hennessey. From a marketing point of view, and staying away from terroir, this would make a lot of sense.

AG: What are the differences among the various sites on Pritchard Hill and the larger Lake Hennessey region you propose?

BL: I’m not sure if there are substantial differences between Cabernet grown near Lake Hennessey or between Colgin, David Arthur or Stagecoach because the growing conditions – rainfall and soils – are similar. Pritchard Hill faces northwest, so there’s a significant difference in temperatures.

On the Kuleto side – across the canyon – on the top, there’s a good chance that the soil profiles and the weather are different. I have a feeling that the soil depth is different.

On the Conn Valley side, some of the soils are alluvial. There’s tufa. And the exposure is more toward the southwest.

If we’re going to embrace the marketing aspect of it, the more broad-based the appellation is, the more interesting it is for consumers, because it’s clear that the appellations have become more about marketing than grape growing.

AG: That brings us to your thoughts on terroir and the AVA system in general.

BL: You had to be an idealist to start in the wine business in the ‘60s. All of our early investigations relied heavily on examination of what went on in Europe. All of us, in the beginning and continuing, looked long and hard at what the French were doing.

Having said that, in an ideal way, I think it would be better if we did the same thing as the French. If we developed single vineyards it would be very clear to consumers what we’re about.

However, ideals will only get you so far. The American wine business is a clear example of capitalism. Our vineyards were not established by potentates and kings. We have developed a model of a winery that has to do with the winery business and increasing the value of it.

What we have is an American wine industry that has goals and the objective is to see those grow. And that necessarily means the whole winemaking culture – rather than focusing on vineyard awareness, which tends to be labor intensive – needs to acquire more land, more vineyards, and to develop blended wines. The idea is to create the image of the winery that has its place in PR and advertising, then to try and convince people of its availability, and to make those winery products attractive. It’s more like the way people sell clothes or cars, rather than terroir. It’s classic American marketing.

AG: At the expense of terroir?

BL: There are two problems with the terroir concept, which is the traditional French way. First, nobody is looking at it here. There isn’t a systematic investigation of what the wines are like and how they’re grown. It happens only randomly.

BL: There are two problems with the terroir concept, which is the traditional French way. First, nobody is looking at it here. There isn’t a systematic investigation of what the wines are like and how they’re grown. It happens only randomly.The second problem is the urgency to sell things. It results in homogenization. The focus, the attention of the consumer, is being drawn somewhere else. Terroir to me is the soils and the way the grapes are expressed. Terroir is not winemaking. But that’s a very narrow view.

Homogenization and commoditization of wine does not emphasize small-production wines from specific areas. We’re training the American taste to enjoy Chardonnay, and Pinot Noir. We have a very difficult time reaching out to Americans, getting them interested in these types of (terroir expressive) wines.

Consolidation is driving the interest of the distributors because they don’t want to talk to anyone unless you have 100,000 cases. What that means is that the taste of American wines is limited to these wines.

It has not only chased away the development of better quality wines but it has discouraged people from trying different things. In the restaurant-culture, sommeliers don’t have the purchasing power, but they’re certainly keeping it alive.

It’s a question of personal experience versus the environment in which they live. It’s clear that it is the younger people who are buying these wines. They like