The Santa Lucia Highlands AVA is now enjoying the limelight as a Central Coast paradise for Pinot Noir.

The Santa Lucia Highlands ascend to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the top names in Pinot.

''...dozens of vineyards have popped up in the ‘Highlands’ to test out the new clones and trellising systems to see if Pinot can be Santa Lucia Highlands’ No. 1 calling card. It seems to be.''

by

Dan Berger

May 2, 2006

As Pinot Noir gains a toehold in the New World, the growing sameness of many New World wines seems to infect the vast majority.

Riper, ever riper, seems to be the mantra of all red wine seekers, driven in large part by the score mongers who ignore regional typicity and go for the gusto. Bigger is better.

So where, you may ask, does a region such as the Santa Lucia Highlands fall? The area does produce a most distinctive sort of Pinot Noir aromatic that has embedded within it a dollop (and occasionally more than a dollop) of noticeable herbal character. It is, technically, a trace of what scientists would call methoxypyrazine, and as such it gives the wine a more Burgundian edge to it with its beet, clove, and bell pepper like notes.

It’s a character that seems to be appreciated by some recent converts to Pinot Noir, but mainly in the most fashionable wines, which are those with 15% alcohol or so. Weight, again, plays a role.

And where does this all come from? Part of it is weather related.

Standing in his vineyard on a late afternoon, Dan Lee looked at his watch.

It was 3:30 p.m. “Just about time for the wind,” he said. Within minutes there was a distinct increase in the zephyr blowing in from the north

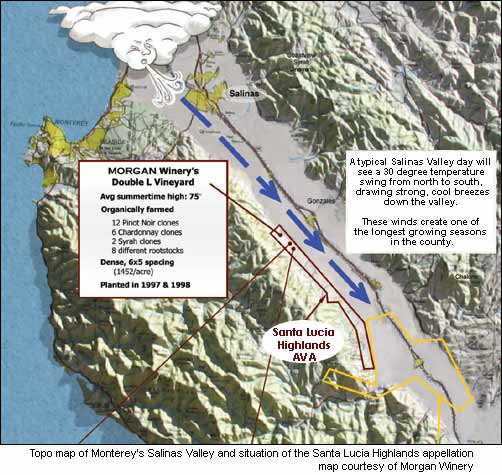

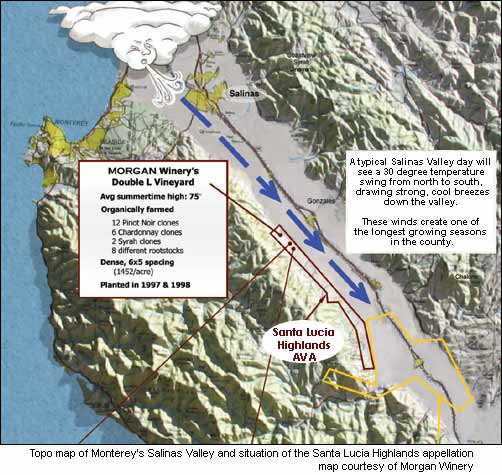

Lee, winemaker for Morgan Winery, knows that taming this breeze, coming in off deep-trenched Monterey Bay, has been a key reason the Santa Lucia Highlands AVA now shows the potential for making some of the best Pinot Noirs in California.

Part of western Monterey County, the ‘Highlands’ have been home to grapes for thirty odd years, but most of the vines were Chardonnay; only a tiny amount of Pinot Noir had ever been attempted here. That came well before proper pruning, trellising and wine making systems had been developed to avoid Pinot Noir’s nastiest habit: being vegetative.

The pyrazine fear, called ‘pyranoia’ by one industry wag, kept many growers away from Pinot Noir for the longest time. But now, this fickle and intransigent fellow, which once fleetingly showed potential in other regions of Monterey County, can be grown here with only a whisper of the dreaded ‘veggies’.

The problem with most of Monterey County through the 1970s and 1980s was the strong wind coming off the bay, racing south into the Salinas Valley. Vine leaves hit by wind respire water. The plant senses that a mini-drought is imminent so they shut down; photosynthesis slows, development slows. And overnight fog keeps the vine in semi-hibernation.

Small amounts of grapes were planted in the ‘Highlands’ in about 1970, but it took another decade before some adventuresome folks discovered that the raised bench-land on the western edge of the valley, just above the growing area called Arroyo Seco, was slightly less affected by the strong breezes.

An early pioneer up here was Rich Smith, who planted the German varietal, Riesling, and whose winery, Paraiso Vineyards, still makes an elegant wine from the grape. To this day, Smith farms some of the best vineyard land in the area. Smith, Lee and others now even grow Syrah here.

They’ve been able to do this because in the last decade trellising systems have been developed that minimize the impact of the wind. It has become particularly evident up here on the Santa Lucia Highlands benchland, above the valley floor.

Tight spacing also has been used to control the speed of the wind. Another factor are the new Pinot clones that are now extant, such as Dijon 115, 667 and 777.

Dan Lee of Morgan said under older growing systems, Pinot Noir ripened too soon and was picked in late August, while much of the flavors were green.

“These days, we know how to grow them, so Pinot is now picked in the third week of September, when they are picking Cabernet in the Napa Valley,” he said. “So the grapes have time to develop flavor without getting too high in sugar.”

Today, dozens of vineyards have popped up in the ‘Highlands’ to test out the new clones and trellising systems to see if Pinot can be Santa Lucia Highlands’ No. 1 calling card. It seems to be.

Wines from the already-famous Gary’s Vineyard are garnering not only acclaim from buyers (at elevated prices), but are making inroads to the other Central Coast Pinot Noir image areas, Santa Barbara’s new find, Santa Rita Hills, as well as southern San Luis Obispo County.

But can it truly be said at this early stage (about a decade into its fame) that Santa Lucia Highlands is the equal of California’s Russian River, Carneros, or Santa Maria Valley? Or, perhaps, is it even better?

To be sure, this emerging Pinot Paradise (also the name of a local event) has already stopped some Pinot sophisticates in their tracks, and has generated some rather fawning copy. But a major drawback I see here is that we have yet to see the real greatness of this Pinot region since there are no aged wines to be had.

I, however, have had one glimpse into the past, a single bottle of a wine that more or less verifies that the future for aged Pinot here is bright. The wine that opened my eyes to Pinot’s potential in the ‘Highlands’ was a bottle of 1979 Stony Ridge, with an appellation designation that simply said ‘Monterey County’.

The circumstances of this wine are fascinating:

I had been asked to bring a bottle of wine to a dinner at the ‘World of Pinot Noir’ in California’s Central Coast. After arguing that mature is better than young, I walked through our cellar to see if there was something of interest. There I found the old Stony Ridge, and recalled that I had loved the wine at a California Grapevine tasting some years earlier.

I went back in my records and found t

Riper, ever riper, seems to be the mantra of all red wine seekers, driven in large part by the score mongers who ignore regional typicity and go for the gusto. Bigger is better.

So where, you may ask, does a region such as the Santa Lucia Highlands fall? The area does produce a most distinctive sort of Pinot Noir aromatic that has embedded within it a dollop (and occasionally more than a dollop) of noticeable herbal character. It is, technically, a trace of what scientists would call methoxypyrazine, and as such it gives the wine a more Burgundian edge to it with its beet, clove, and bell pepper like notes.

It’s a character that seems to be appreciated by some recent converts to Pinot Noir, but mainly in the most fashionable wines, which are those with 15% alcohol or so. Weight, again, plays a role.

And where does this all come from? Part of it is weather related.

Standing in his vineyard on a late afternoon, Dan Lee looked at his watch.

It was 3:30 p.m. “Just about time for the wind,” he said. Within minutes there was a distinct increase in the zephyr blowing in from the north

Lee, winemaker for Morgan Winery, knows that taming this breeze, coming in off deep-trenched Monterey Bay, has been a key reason the Santa Lucia Highlands AVA now shows the potential for making some of the best Pinot Noirs in California.

Part of western Monterey County, the ‘Highlands’ have been home to grapes for thirty odd years, but most of the vines were Chardonnay; only a tiny amount of Pinot Noir had ever been attempted here. That came well before proper pruning, trellising and wine making systems had been developed to avoid Pinot Noir’s nastiest habit: being vegetative.

The pyrazine fear, called ‘pyranoia’ by one industry wag, kept many growers away from Pinot Noir for the longest time. But now, this fickle and intransigent fellow, which once fleetingly showed potential in other regions of Monterey County, can be grown here with only a whisper of the dreaded ‘veggies’.

The problem with most of Monterey County through the 1970s and 1980s was the strong wind coming off the bay, racing south into the Salinas Valley. Vine leaves hit by wind respire water. The plant senses that a mini-drought is imminent so they shut down; photosynthesis slows, development slows. And overnight fog keeps the vine in semi-hibernation.

Small amounts of grapes were planted in the ‘Highlands’ in about 1970, but it took another decade before some adventuresome folks discovered that the raised bench-land on the western edge of the valley, just above the growing area called Arroyo Seco, was slightly less affected by the strong breezes.

An early pioneer up here was Rich Smith, who planted the German varietal, Riesling, and whose winery, Paraiso Vineyards, still makes an elegant wine from the grape. To this day, Smith farms some of the best vineyard land in the area. Smith, Lee and others now even grow Syrah here.

They’ve been able to do this because in the last decade trellising systems have been developed that minimize the impact of the wind. It has become particularly evident up here on the Santa Lucia Highlands benchland, above the valley floor.

Tight spacing also has been used to control the speed of the wind. Another factor are the new Pinot clones that are now extant, such as Dijon 115, 667 and 777.

Dan Lee of Morgan said under older growing systems, Pinot Noir ripened too soon and was picked in late August, while much of the flavors were green.

“These days, we know how to grow them, so Pinot is now picked in the third week of September, when they are picking Cabernet in the Napa Valley,” he said. “So the grapes have time to develop flavor without getting too high in sugar.”

Today, dozens of vineyards have popped up in the ‘Highlands’ to test out the new clones and trellising systems to see if Pinot can be Santa Lucia Highlands’ No. 1 calling card. It seems to be.

Wines from the already-famous Gary’s Vineyard are garnering not only acclaim from buyers (at elevated prices), but are making inroads to the other Central Coast Pinot Noir image areas, Santa Barbara’s new find, Santa Rita Hills, as well as southern San Luis Obispo County.

But can it truly be said at this early stage (about a decade into its fame) that Santa Lucia Highlands is the equal of California’s Russian River, Carneros, or Santa Maria Valley? Or, perhaps, is it even better?

To be sure, this emerging Pinot Paradise (also the name of a local event) has already stopped some Pinot sophisticates in their tracks, and has generated some rather fawning copy. But a major drawback I see here is that we have yet to see the real greatness of this Pinot region since there are no aged wines to be had.

I, however, have had one glimpse into the past, a single bottle of a wine that more or less verifies that the future for aged Pinot here is bright. The wine that opened my eyes to Pinot’s potential in the ‘Highlands’ was a bottle of 1979 Stony Ridge, with an appellation designation that simply said ‘Monterey County’.

The circumstances of this wine are fascinating:

I had been asked to bring a bottle of wine to a dinner at the ‘World of Pinot Noir’ in California’s Central Coast. After arguing that mature is better than young, I walked through our cellar to see if there was something of interest. There I found the old Stony Ridge, and recalled that I had loved the wine at a California Grapevine tasting some years earlier.

I went back in my records and found t