An interview with fourth generation winemaker Bill Cooper reveals his care and respect for the land that is manifested in his wines.

Steward of the Terroir:

Cooper-Garrod's Bill Cooper

My overriding concern is that we be good stewards of the land, taking care of it for future generations. The Garrod side of our family has been farming in the Santa Cruz Mountains for over 100 years, and I believe practicing sustainable agriculture is what has made that possible.

~Bill Cooper

by

Laura Ness

May 5, 2007

Laura Ness (LN): How far back have grapes been planted at the Cooper-Garrod site? Do you know what were the original varieties? Origins?

Bill Cooper (BC): In 1972, our founding winemaker, George Cooper, established a one-acre vineyard around his home with Cabernet Sauvignon scion wood from the original, no-longer extant Paul Masson vineyard. This was to be George’s “retirement project,”

Cooper-Garrod Estate Winery’s

Bill Cooper.a change of pace from being chief research test pilot at NASA’s Ames Research Center, In the words of his daughter, Barbara: it is “just one of Dad’s projects that got out of hand.”

LN: When you got involved in winemaking, what varieties did you originally plant? What did well? What did not?

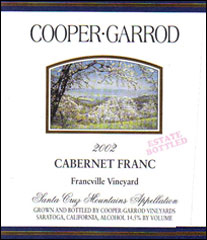

BC: In 1979 and 80, George’s nephew, Jan Garrod, planted five acres of Chardonnay to complement the Cab and begin the gradual replacement of aging orchards with vineyards. In 1985, five acres of Cabernet Franc followed with scion wood from a neighboring vineyard established by French immigrant Pierre Pourrey in the early 1900’s. Most recently, in 1998, Syrah was planted with cuttings from nearby Mariadon Vineyard and Viognier with suitcase cuttings imported by Randall Graham in the late 70s.

LN: What have been some of your most fruitful experiments in viticulture? Some of the best practices you have learned over the years?

BC: By far, the most “fruitful” experiment has been the diversity of high-quality grapes that can be grown in the Santa Cruz Mountains. On our property alone, there are vineyards sourced to all the major grape-growing regions of France: Bordeaux, Burgundy, Loire, and Rhone. Site and root stock selection remain important, but the variety of grapes for world-class wine that can be grown here is truly amazing.

LN: What are the biggest challenges to viticulture in the Santa Cruz Mountains?

BC: Because the Santa Cruz Mountains is a great place to live, the biggest challenge is keeping economically-viable agriculture here. In this regard, the Williamson Act is, I believe, a very progressive piece of legislation and singularly responsible for the maintenance and growth of agriculture, not just wine grapes, in California. That said, hillside agriculture requires special effort, especially for erosion control, which is one of the reasons we mow, rather than plow, our vineyards.

LN: What are the most important things growers need to be paying attention to right now? Talk about sustainable agriculture, water issues, pest prevention, soil amendments, etc.

BC: We know how to farm and/or make wine. My overriding concern is that we be good stewards of the land, taking care of it for future generations. The Garrod side of our family has been farming in the Santa Cruz Mountains for over 100 years (I am the fourth generation), and I believe practicing sustainable agriculture is what has made that possible.

Sustainable activities are those that are ecologically sound, socially responsible, and economically viable. The California Code of Sustainable Winegrowing Self-Assessment Workbook contains 14 chapters that cover everything from air quality to viticulture and water quality and conservation. Written by a joint committee of growers and vintners, the workbook has 227 criteria for self-assessment. The criteria, in turn, enable the Cooper-Garrod sources Cabernet Sauvignon grapes from Lone Oak Vineyard in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

Cooper-Garrod sources Cabernet Sauvignon grapes from Lone Oak Vineyard in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

[Image courtesy of Ralph Andrea Photography, www.rwaphoto.com]participants to measure their level of sustainability and to learn - in the workbook, in workshops, and on-line - about ways to improve their practices. As they do so, it is important to develop and maintain good neighbor and community relations so our neighbors understand what we are doing and why; this is actually the topic of another chapter of the workbook. Thus, I believe education and self-improvement are life-long processes and the keys to success.

LN: Are there any areas in which you think the SCMWA could be doing a better job? What about the Viticulture association? (Note: the Winegrowers Association and Viticulture Association are two separate entities, with the Viticulture group primarily focusing on vineyard management issues.)

BC: A better job, no. Both associations are intimately involved in improving quality wine grapes and in promoting the image of appellation.

Looking ahead, however, wineries and vineyards that have not yet completed their Sustainable Winegrowing self-assessment and their Action Plans for continual self-improvement will find themselves falling behind as their neighbors, and other AVA’s, continue to improve. I would also like to see discussion of a merged association that would promote both the wines and the grapes of the region.

LN: How has the perception of SCM as an appellation changed over the last ten years? What do you think the outside world thinks of us now compared to 5 or 10 years ago?

BC: We’re definitely on the map in terms of grape and wine quality, but our relatively small grape acreage means there is a very small amount of wine that is actually available for distribution outside of the Bay Area.

LN: Do you think the region would benefit from having smaller micro-appellations to account for climate and topography differences?

BC: We’re not Napa, or even Paso Robles, in terms of size so I view smaller “micro-appellations” as balkanization rather than meaningful diversity. We need to keep our marketing effort focused on the appellation as a whole. At the same time, the appellation is too big to visit with one wine trail or two. We do need to develop local wine trails that facilitate local visits without detracting from the big picture of the Santa Cruz Mountains. Here again, I would like to see development of a Santa Cruz Mountains Wine Country Alliance that combines the efforts of the wineries, wine grape growers, and local chambers.

Bill Cooper (BC): In 1972, our founding winemaker, George Cooper, established a one-acre vineyard around his home with Cabernet Sauvignon scion wood from the original, no-longer extant Paul Masson vineyard. This was to be George’s “retirement project,”

Cooper-Garrod Estate Winery’s

Bill Cooper.

LN: When you got involved in winemaking, what varieties did you originally plant? What did well? What did not?

BC: In 1979 and 80, George’s nephew, Jan Garrod, planted five acres of Chardonnay to complement the Cab and begin the gradual replacement of aging orchards with vineyards. In 1985, five acres of Cabernet Franc followed with scion wood from a neighboring vineyard established by French immigrant Pierre Pourrey in the early 1900’s. Most recently, in 1998, Syrah was planted with cuttings from nearby Mariadon Vineyard and Viognier with suitcase cuttings imported by Randall Graham in the late 70s.

LN: What have been some of your most fruitful experiments in viticulture? Some of the best practices you have learned over the years?

BC: By far, the most “fruitful” experiment has been the diversity of high-quality grapes that can be grown in the Santa Cruz Mountains. On our property alone, there are vineyards sourced to all the major grape-growing regions of France: Bordeaux, Burgundy, Loire, and Rhone. Site and root stock selection remain important, but the variety of grapes for world-class wine that can be grown here is truly amazing.

LN: What are the biggest challenges to viticulture in the Santa Cruz Mountains?

BC: Because the Santa Cruz Mountains is a great place to live, the biggest challenge is keeping economically-viable agriculture here. In this regard, the Williamson Act is, I believe, a very progressive piece of legislation and singularly responsible for the maintenance and growth of agriculture, not just wine grapes, in California. That said, hillside agriculture requires special effort, especially for erosion control, which is one of the reasons we mow, rather than plow, our vineyards.

LN: What are the most important things growers need to be paying attention to right now? Talk about sustainable agriculture, water issues, pest prevention, soil amendments, etc.

BC: We know how to farm and/or make wine. My overriding concern is that we be good stewards of the land, taking care of it for future generations. The Garrod side of our family has been farming in the Santa Cruz Mountains for over 100 years (I am the fourth generation), and I believe practicing sustainable agriculture is what has made that possible.

Sustainable activities are those that are ecologically sound, socially responsible, and economically viable. The California Code of Sustainable Winegrowing Self-Assessment Workbook contains 14 chapters that cover everything from air quality to viticulture and water quality and conservation. Written by a joint committee of growers and vintners, the workbook has 227 criteria for self-assessment. The criteria, in turn, enable the

Cooper-Garrod sources Cabernet Sauvignon grapes from Lone Oak Vineyard in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

Cooper-Garrod sources Cabernet Sauvignon grapes from Lone Oak Vineyard in the Santa Cruz Mountains.[Image courtesy of Ralph Andrea Photography, www.rwaphoto.com]

LN: Are there any areas in which you think the SCMWA could be doing a better job? What about the Viticulture association? (Note: the Winegrowers Association and Viticulture Association are two separate entities, with the Viticulture group primarily focusing on vineyard management issues.)

BC: A better job, no. Both associations are intimately involved in improving quality wine grapes and in promoting the image of appellation.

Looking ahead, however, wineries and vineyards that have not yet completed their Sustainable Winegrowing self-assessment and their Action Plans for continual self-improvement will find themselves falling behind as their neighbors, and other AVA’s, continue to improve. I would also like to see discussion of a merged association that would promote both the wines and the grapes of the region.

LN: How has the perception of SCM as an appellation changed over the last ten years? What do you think the outside world thinks of us now compared to 5 or 10 years ago?

BC: We’re definitely on the map in terms of grape and wine quality, but our relatively small grape acreage means there is a very small amount of wine that is actually available for distribution outside of the Bay Area.

LN: Do you think the region would benefit from having smaller micro-appellations to account for climate and topography differences?

BC: We’re not Napa, or even Paso Robles, in terms of size so I view smaller “micro-appellations” as balkanization rather than meaningful diversity. We need to keep our marketing effort focused on the appellation as a whole. At the same time, the appellation is too big to visit with one wine trail or two. We do need to develop local wine trails that facilitate local visits without detracting from the big picture of the Santa Cruz Mountains. Here again, I would like to see development of a Santa Cruz Mountains Wine Country Alliance that combines the efforts of the wineries, wine grape growers, and local chambers.

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,