Big fish eats little fish: Byron Vineyard has been gobbled up by a series of corporate owners, all of whom recognized the quality of the wines. Now nurtured by Jackson Family Farms, Byron continues to flourish.

Byron Vineyard and Winery:

Perseverance Pays Off

I tend to think that a truly great wine is one that is "yummy" while giving a sense of place. If you can't do the “yummy” thing, you probably should plant a different variety

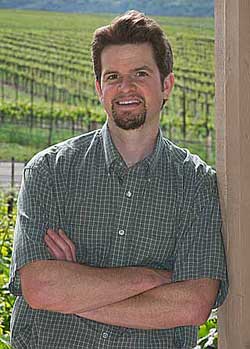

~Jonathan Nagy, Winemaker, Byron Winery.

by

Dennis Schaefer

March 8, 2007

Jonathan Nagy (JN): As a winemaker, I think the most important factor is that Santa Maria Valley is an east-west running valley in close proximity to the ocean. The maritime influence keeps the temperatures moderate throughout the year. Because of this, we get a very early bud break (average of mid-February) and mild temperatures during harvest. The mild harvest temperatures translate to longer hang time which allows flavor development to be more in line with sugar/acid development. Mild temperatures are very important for Pinot. If things are too hot, you start getting "stewed" fruit characteristics and have washed out colors.

DS: What are the defining characteristics of the Santa Maria Valley appellation, particularly the vineyards that you’ve worked with?

JN: Of Santa Maria Valley, as a whole: high natural acidity, complex flavor profiles (not just fruit characteristics, but also mineral, earthy, floral depending on varietal), and length on the palate. Working your way up the valley from east to west, a lot of the differences in vineyards seem to relate to how the fog burns off during harvest.

Jonathan Nagy has remained winemaker at Byron through a series of owners and occasional financial uncertainties.

Moving up the valley to Bien Nacido, it’s a little warmer and the fog burns off sooner. Pinot Noirs will have floral, dark cherry, earthy, and forest floor. There’s a little bigger tannin structure in this vineyard and you get more concentration from the blocks higher on the bench, such as Q block, 1-West, block 8. In Julia's Vineyard, Pinot Noirs start getting a lot of the classic Pinot Noir fruit with floral (rose petal) and it’s less earthy. Katherine’s Vineyard Chardonnays have a nice mixture of citrus and tropical fruit. Nielson Vineyard is one of the first for the fog to burn off. Pinot Noirs have lots of dark fruit and floral, as well as a bigger tannin structure. Chardonnays start getting more mineral, citrus, and orange blossom notes.

DS: Nielson Vineyard is the oldest commercial vineyard in Santa Barbara County. What year was it planted and what was spacing and orientation? What are the yields? Have you done any replanting there?

JN: It was planted in 1964 with east-west rows and 12 x 6 spacing. Yields are 1 to 1.5 tons per acre in a normal year. We've only re-planted the occasional vine that gets taken out by a gopher or tractor.

DS: What changes were made in the vineyard and in farming practices when Robert Mondavi bought Byron? I understand the infusion of Mondavi money helped fund experimental plantings?

JN: I think the biggest changes were the replanting of the Byron vineyard. The first thing they did was plant an experimental Pinot block trellised to a vertical-shoot position. Every 4 rows they changed clone and rootstock trying to find the best combinations for the vineyard. They also changed spacing within the trial block.

DS: Is there something germane to your soils, climate or region which makes these clones the most desirable?

JN: From what I've seen, preferred clones differ from region to region. So I think terroir plays into the decision of what clone is best. Just as an aside, it seems that as the blocks get older, there tends to be less difference between clones.

DS: Do you keep the various clones separate in the winery?

JN: Lately, we have been keeping clones that are really nice separate. That’s nice for blending purposes. Most of the other clones are co-fermented. I like the idea that the co-fermentation is making a more balanced and expressive wine. I've never done a trial to prove this though.

DS: Are there any specific winemaking techniques you employ that you think helps express the regional character of the wines?

JN: The general philosophy is to work with it in the fermenter: aggressive punch down, pump over, rack-and-returns, and then leave it alone once it is in barrel. I kind of see it like unlocking the vineyard in a low alcohol environment, then trying to preserve what you have unlocked.

DS: And do you strive to express that regional difference or mute it?

JN: I try to preserve regional differences. This whole discussion actually came up at a tasting group, with many varying views. I tend to think that a truly great wine is one that is "yummy" while giving a sense of place. If you can't do the “yummy” thing, you probably should plant a different variety. We had some Cab Franc planted here that was terrible. Its sense of place was bell pepper. So we ripped it out and have planted Pinot.

DS: Do you think the use of new oak tends to obscure mute regional character?

JN: One over-oaked wine tastes just like the next one regardless of region. We use 25 - 40 percent new oak

Byron Vineyard and Winery in the Santa Maria Valley AVA.

DS: With the tendency toward longer hang times and greater ripeness, thus producing higher alcohols, do you think those higher alcohol levels obscure the regional character?

JN: It's kind of a tight rope act. Too much alcohol (too ripe in general), definitely obscures regional differences, but you want to pick ripe enough that you have good flavors. We tend to look for flavor first, then deal with potential alcohol later for all varietals.

DS: How do you deal with potential alcohol, if you feel it’s too high or distracting?

JN: You could deal with the alcohol in two ways: saignee a percent off, then add that percent back in water to lower the Brix or remove alcohol via filtration. I prefer the former method becau

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,