The Monticello AVA was named after

Thomas Jefferson's plantation and mansion

of the same name. Jefferson was America's forefather of viticulture.

Realizing Jefferson’s Dream:

Oakencroft Pioneers Great Wine in Virginia

An in-depth interview with Virginia vineyard pioneer Phillip Ponton reveals the history and future of wine from this most historic of American winegrowing regions.

by

Barbara Ensrud

April 30, 2007

Barbara Ensrud (BE): How did you come to Oakencroft, and what was it like in the early years?

Phillip Ponton (PP): I grew up in this area on a cattle farm that my family has owned since the 1840s. In the mid-70s, I met Gabriele Rausse, who was sent here from Italy by the Zonin family to start Barboursville Winery. I got my first taste of viticulture helping Gabriele plant the early vines at Barboursville. After that, I had various jobs at nuclear plants and oil rigs around the south, but then my wife and I wanted to come back to Virginia.

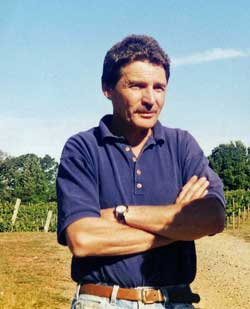

After 25 years as vineyard manager at Oakencroft Vineyard & Winery, Phillip Ponton retires this year.

When the owners of Oakencroft needed someone to help start the vineyard, Gabriele recommended me. I was hired on April 21, 1982—I remember it clearly because it was the beginning of a very different life for me. The transition from an offshore oil rig in Texas to sitting across the table from John and Felicia Rogan was pretty dramatic; they were the most sophisticated and glamorous people I had ever worked with.

The Rogans had a one-acre vineyard near their house and rose garden, half Chardonnay and half Seyval Blanc. The winery was under construction on another part of the property with a vineyard laid out on the hill rising behind it. That spring we planted 2200 Chardonnay vines and 2200 Seyval Blanc. In the four to five years following, we planted various varieties every spring or fall until we filled about 17 acres.

BE: Albemarle County was an untried region for wine grapes, wasn’t it? What were the biggest challengers that growers faced?

PP: During the early years, I was caught up in the wave of excitement surrounding the Virginia wine industry, meeting the people in Albemarle and surrounding counties who were passionately engaged in this new - for us, anyway - agricultural endeavor. The learning curve proved to be steep, but I think it was the passion and excitement that powered us through all the mistakes we made. The biggest one was planting grapes on land we happened to have instead of finding the right site.

One of our earliest mistakes at Oakencroft was the disastrous planting of Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon. Not only was the site too low, making our notorious spring frosts a problem, the rich soil created too much vigor. We eventually pulled out all the Merlot and Cabernet, replacing them with Chambourcin and Traminette - both now profitable varieties for us. We stand now at 11 acres of hybrids and 3.5 acres of vinifera. We later added back the Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon, both up the hill now, with better drainage and better clones.

BE: What would you say was the turning point for vinifera in Virginia - the point at which it was felt that it was the direction to go in producing wines that would gain attention for Virginia?

PP: It’s difficult to say exactly when the turning point came. Even in the early eighties, we didn’t really know what we were doing - or what to do with what we had. We got a tremendous boost in technical expertise in 1985 when Tony Wolf (a Cornell-trained viticulturalist) and enologist Bruce Zoecklein were hired by Virginia Tech. It was then that the science of matching varieties, rootstocks and clonal selection started. Without question, the Virginia wine industry wouldn’t be where it is today without their guidance. Other factors included getting more temperature control during fermentation to get better aromatics. We also went to gentler fruit handling. In the early days we had an old screw press which ground up everything, including pips and bits of stem. Now we do smaller lots, use sorting tables, and have a gentler press. We do much less pumping over now. We start fermentations cold, then rack off the lees into barrels and don’t do any pumping until time for bottling. We pay greater attention to different yeasts, and even use some native yeasts that add depth and complexity.

Another huge difference is in bottling. Most of the smaller wineries, including Oakencroft and even some of the larger wineries, began using mobile bottling lines around 10 years ago. I shudder when I think back on our primitive early bottling procedures - by hand, which resulted in oxidation.

These changes resulted in better wines, so that by the late eighties, some good wines - Chardonnay, Merlot - were being made that got media attention in Washington and New York and elsewhere nationally. That created interest in the area and people with money started looking for land to plant vineyards and start wineries. Land prices were a lot more reasonable then, but today people are still buying land and putting in new vineyards. They’re making a new map of the Monticello Wine Trail this spring to reflect the growth in wineries. The biggest changes, however, have been in viticulture. Our mantra has been “winemaking is done in the vineyard.”

BE: In your 25 years of viticultural experience in Albemarle County, and specifically Oakencroft, what have been the most significant challenges?

PP: It’s been a continuous journey of discoveries, and still is. Our big challenge here is rain during harvest, so choosing sites for good drainage is critical. The granite-based clay soil here soaks up and retains water. Cab Franc is a good example; grown on water-retentive bottom land it does poorly, but on upland sites where drainage is better, it grows well. People are now going to old orchard sites on hillsides to plant vineyards. They’re also using drain tiles to drain off excess water from flatter sites.

Growers are seriously trying to keep vine size down to reduce vigor, which allows us to cut down on doing three to four hedgings a season. There are two schools of thought here: one leans to dense planting; some are narrowing to four feet between vines, and seven between rows. I’m looking for five feet between vines, nine or ten feet between rows which our equipment can handle.

Another way to increase competition for nutrients and keep vines smaller is to allow grasses and cover crops under the vines and between rows. I used to keep the vineyard immaculate, using herbicides to kill off weeds and undergrowth but I stopped that, and even plant clover in some parts of the vineyard to take up some of that soil richness. We also limit yields pretty severely. Chambourcin, for instance, will easily yield five tons or more per acre, but we hold it to two and a half and get more flavor and deeper color.

We manage canopy, too. The trellising here is Smart-Dyson, with some shoots going straight up but others draping over in a ballerina effect. I have found, too, that if I pull le

Phillip Ponton (PP): I grew up in this area on a cattle farm that my family has owned since the 1840s. In the mid-70s, I met Gabriele Rausse, who was sent here from Italy by the Zonin family to start Barboursville Winery. I got my first taste of viticulture helping Gabriele plant the early vines at Barboursville. After that, I had various jobs at nuclear plants and oil rigs around the south, but then my wife and I wanted to come back to Virginia.

After 25 years as vineyard manager at Oakencroft Vineyard & Winery, Phillip Ponton retires this year.

When the owners of Oakencroft needed someone to help start the vineyard, Gabriele recommended me. I was hired on April 21, 1982—I remember it clearly because it was the beginning of a very different life for me. The transition from an offshore oil rig in Texas to sitting across the table from John and Felicia Rogan was pretty dramatic; they were the most sophisticated and glamorous people I had ever worked with.

The Rogans had a one-acre vineyard near their house and rose garden, half Chardonnay and half Seyval Blanc. The winery was under construction on another part of the property with a vineyard laid out on the hill rising behind it. That spring we planted 2200 Chardonnay vines and 2200 Seyval Blanc. In the four to five years following, we planted various varieties every spring or fall until we filled about 17 acres.

BE: Albemarle County was an untried region for wine grapes, wasn’t it? What were the biggest challengers that growers faced?

PP: During the early years, I was caught up in the wave of excitement surrounding the Virginia wine industry, meeting the people in Albemarle and surrounding counties who were passionately engaged in this new - for us, anyway - agricultural endeavor. The learning curve proved to be steep, but I think it was the passion and excitement that powered us through all the mistakes we made. The biggest one was planting grapes on land we happened to have instead of finding the right site.

One of our earliest mistakes at Oakencroft was the disastrous planting of Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon. Not only was the site too low, making our notorious spring frosts a problem, the rich soil created too much vigor. We eventually pulled out all the Merlot and Cabernet, replacing them with Chambourcin and Traminette - both now profitable varieties for us. We stand now at 11 acres of hybrids and 3.5 acres of vinifera. We later added back the Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon, both up the hill now, with better drainage and better clones.

BE: What would you say was the turning point for vinifera in Virginia - the point at which it was felt that it was the direction to go in producing wines that would gain attention for Virginia?

PP: It’s difficult to say exactly when the turning point came. Even in the early eighties, we didn’t really know what we were doing - or what to do with what we had. We got a tremendous boost in technical expertise in 1985 when Tony Wolf (a Cornell-trained viticulturalist) and enologist Bruce Zoecklein were hired by Virginia Tech. It was then that the science of matching varieties, rootstocks and clonal selection started. Without question, the Virginia wine industry wouldn’t be where it is today without their guidance. Other factors included getting more temperature control during fermentation to get better aromatics. We also went to gentler fruit handling. In the early days we had an old screw press which ground up everything, including pips and bits of stem. Now we do smaller lots, use sorting tables, and have a gentler press. We do much less pumping over now. We start fermentations cold, then rack off the lees into barrels and don’t do any pumping until time for bottling. We pay greater attention to different yeasts, and even use some native yeasts that add depth and complexity.

Another huge difference is in bottling. Most of the smaller wineries, including Oakencroft and even some of the larger wineries, began using mobile bottling lines around 10 years ago. I shudder when I think back on our primitive early bottling procedures - by hand, which resulted in oxidation.

These changes resulted in better wines, so that by the late eighties, some good wines - Chardonnay, Merlot - were being made that got media attention in Washington and New York and elsewhere nationally. That created interest in the area and people with money started looking for land to plant vineyards and start wineries. Land prices were a lot more reasonable then, but today people are still buying land and putting in new vineyards. They’re making a new map of the Monticello Wine Trail this spring to reflect the growth in wineries. The biggest changes, however, have been in viticulture. Our mantra has been “winemaking is done in the vineyard.”

BE: In your 25 years of viticultural experience in Albemarle County, and specifically Oakencroft, what have been the most significant challenges?

PP: It’s been a continuous journey of discoveries, and still is. Our big challenge here is rain during harvest, so choosing sites for good drainage is critical. The granite-based clay soil here soaks up and retains water. Cab Franc is a good example; grown on water-retentive bottom land it does poorly, but on upland sites where drainage is better, it grows well. People are now going to old orchard sites on hillsides to plant vineyards. They’re also using drain tiles to drain off excess water from flatter sites.

Growers are seriously trying to keep vine size down to reduce vigor, which allows us to cut down on doing three to four hedgings a season. There are two schools of thought here: one leans to dense planting; some are narrowing to four feet between vines, and seven between rows. I’m looking for five feet between vines, nine or ten feet between rows which our equipment can handle.

Another way to increase competition for nutrients and keep vines smaller is to allow grasses and cover crops under the vines and between rows. I used to keep the vineyard immaculate, using herbicides to kill off weeds and undergrowth but I stopped that, and even plant clover in some parts of the vineyard to take up some of that soil richness. We also limit yields pretty severely. Chambourcin, for instance, will easily yield five tons or more per acre, but we hold it to two and a half and get more flavor and deeper color.

We manage canopy, too. The trellising here is Smart-Dyson, with some shoots going straight up but others draping over in a ballerina effect. I have found, too, that if I pull le

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,