Analyzing the sometimes schizophrenic personality of a single vineyard is a big part of producing “wines of place”

Nickel & Nickel's Dirk Hampson on Terroir:

Understanding the cause and solution of “Multiple Terroir Syndrome”

by

Alan Goldfarb

March 31, 2006

Dirk Hampson and his partners at Far Niente announced less than 10 years ago they were starting a second winery whose entire focus would be single vineyard-designated wines, I thought it to be an ambitious and worthwhile project. After all, the folks at Domaine de la Romanée-Conti had staked their fame – and considerable fortune – on producing some of the world’s most highly regarded single-vineyard Burgundies. But that’s France, where terroir, especially in Burgundy, counts for something.

But here in California, where a vineyard’s special characteristics are mostly lost to the scrim of overripe fruit augmented by the sweetness of the commensurate alcohol and exacerbated by the char of oak, all is nearly for naught. To make a half-dozen or so single vineyard Cabernets, Chardonnays, Merlots, and Syrahs from about 10 different wine-growing regions – with more on the drawing board – I thought was folly. How will an American consumer, already addled by the esoteric nature of wine, ever be able to select and understand the veritable blitzkrieg of wines which the well-intended folks at Nickel & Nickel are making?

But listening to Hampson over the years – most especially when he addressed a group of scientists and winemakers at the recently completed terroir conference at UC Davis – Nickel & Nickel’s alchemic plan becomes more illuminated; or perhaps not.

Hampson, in his talk, “It’s Not Just the Dirt,” concedes that the task at his Oakville winery is prodigious when he acknowledges, “We can’t get off the treadmill (of this process). After all, we’re in business. … But how (do) we figure out what technical decisions we make to each vineyard and how do you choose which of these techniques are practical, all with terroir philosophy in mind?

“For us,” continued Hampson, whose wines are all made using 100 percent of the labeled variety, “terroir is all about philosophy. (But) when did philosophy ever make things clear?”

Hampson believes that terroir is “about personality (of a vineyard), the character of a place, and personal interpretation and emphasis (of that place).” Additionally he said, “Perhaps wine from a unique place is different, but does that define terroir? Terroir is something that is more than what is practical … Taste is often lost in words.”

Hampson asked rhetorically of the room filled with about 200 people, “What is a true terroir?

“There are no cliff notes at our winery to make our wines (and) how do we communicate those to our customers?”

Then he asks a strange question, “Can a vineyard suffer from terroir schizophrenia?” And then answers it with a simple, “Yes.”

He calls it Multiple Terroir Syndrome or MTS and cites the great Burgundy Chardonnay vineyard, Le Montrachet, as an example.

“It has uniform soil but there are many wineries which get fruit from there and they’re (the wines) all different. A vertical tasting will reveal the commonalities… (but) it will also show the personality of the winemakers. Each has a different idea of the personality of Le Montrachet.

“The cause and solution of MTS is very much a part of personal interpretation. Like a painting of a still life, (multiple interpretations) are equally valid expressions.”

Toward that end, Hampson and his N&N crew employ practical, rather than standardized regimens in each of the 18 vineyards from which they sources fruit, which include sites in St. Helena, Coombsville, Oakville, Howell Mountain, Carneros, Diamond Mountain, Jamieson Canyon, and the Russian River Valley.

“The best way to get practical is through vineyard personality assessment,” he said.

But he concedes, even that is not a facile thing to do. “I don’t understand my own personality and I have kids. How am I supposed to understand the personality of 18 different vineyards?”

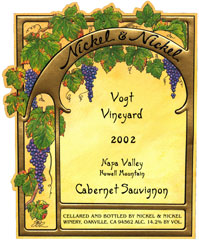

Nonetheless, in the Vogt Vineyard on Howell Mountain, for instance, from which N&N produces one of its eight Cabernets, the soils are shallow, gravelly, weak and well-drained. It’s the last spot to “bud-out” in the Napa Valley. The berries are small, the vineyard never gives more than three tons to the acre, and the wines from it are dark and have tannins “that will knock you over.”

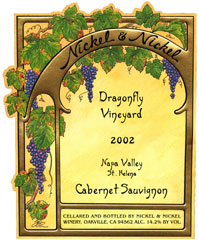

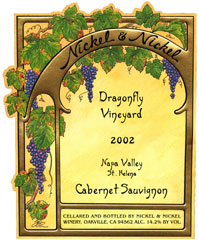

On the other hand, The Dragonfly Vineyard in St. Helena on the valley floor, which produces another of N&N’s Cabs, is one of the warmest spots in the region with very deep, alluvial soils that are full of cobbles. The viticulture is the same as up at Vogt but Dragonfly is the first vineyard in N&N’s portfolio to get harvested; and it makes a wine with silky tannins.

“Our wines don’t make themselves. Every decision has to be made,” explained Hampson, “and non-intervention is for marketing (departments) only.

“I don’t want to confuse people with ‘wines of place’ and ‘wines of technique’… But a lot of it is learning the place. More subtle wines demand more aggressive handling, made through practical decisions.

“We make wines through personality (of the place).”

~ Alan Goldfarb, Napa Editor

To comment on Alan Goldfarb’s writings and thoughts, contact him at a.goldfarb@appellationamerica.com

But here in California, where a vineyard’s special characteristics are mostly lost to the scrim of overripe fruit augmented by the sweetness of the commensurate alcohol and exacerbated by the char of oak, all is nearly for naught. To make a half-dozen or so single vineyard Cabernets, Chardonnays, Merlots, and Syrahs from about 10 different wine-growing regions – with more on the drawing board – I thought was folly. How will an American consumer, already addled by the esoteric nature of wine, ever be able to select and understand the veritable blitzkrieg of wines which the well-intended folks at Nickel & Nickel are making?

But listening to Hampson over the years – most especially when he addressed a group of scientists and winemakers at the recently completed terroir conference at UC Davis – Nickel & Nickel’s alchemic plan becomes more illuminated; or perhaps not.

Hampson, in his talk, “It’s Not Just the Dirt,” concedes that the task at his Oakville winery is prodigious when he acknowledges, “We can’t get off the treadmill (of this process). After all, we’re in business. … But how (do) we figure out what technical decisions we make to each vineyard and how do you choose which of these techniques are practical, all with terroir philosophy in mind?

“For us,” continued Hampson, whose wines are all made using 100 percent of the labeled variety, “terroir is all about philosophy. (But) when did philosophy ever make things clear?”

Hampson believes that terroir is “about personality (of a vineyard), the character of a place, and personal interpretation and emphasis (of that place).” Additionally he said, “Perhaps wine from a unique place is different, but does that define terroir? Terroir is something that is more than what is practical … Taste is often lost in words.”

Hampson asked rhetorically of the room filled with about 200 people, “What is a true terroir?

“There are no cliff notes at our winery to make our wines (and) how do we communicate those to our customers?”

Then he asks a strange question, “Can a vineyard suffer from terroir schizophrenia?” And then answers it with a simple, “Yes.”

He calls it Multiple Terroir Syndrome or MTS and cites the great Burgundy Chardonnay vineyard, Le Montrachet, as an example.

“It has uniform soil but there are many wineries which get fruit from there and they’re (the wines) all different. A vertical tasting will reveal the commonalities… (but) it will also show the personality of the winemakers. Each has a different idea of the personality of Le Montrachet.

“The cause and solution of MTS is very much a part of personal interpretation. Like a painting of a still life, (multiple interpretations) are equally valid expressions.”

Toward that end, Hampson and his N&N crew employ practical, rather than standardized regimens in each of the 18 vineyards from which they sources fruit, which include sites in St. Helena, Coombsville, Oakville, Howell Mountain, Carneros, Diamond Mountain, Jamieson Canyon, and the Russian River Valley.

“The best way to get practical is through vineyard personality assessment,” he said.

But he concedes, even that is not a facile thing to do. “I don’t understand my own personality and I have kids. How am I supposed to understand the personality of 18 different vineyards?”

Nonetheless, in the Vogt Vineyard on Howell Mountain, for instance, from which N&N produces one of its eight Cabernets, the soils are shallow, gravelly, weak and well-drained. It’s the last spot to “bud-out” in the Napa Valley. The berries are small, the vineyard never gives more than three tons to the acre, and the wines from it are dark and have tannins “that will knock you over.”

On the other hand, The Dragonfly Vineyard in St. Helena on the valley floor, which produces another of N&N’s Cabs, is one of the warmest spots in the region with very deep, alluvial soils that are full of cobbles. The viticulture is the same as up at Vogt but Dragonfly is the first vineyard in N&N’s portfolio to get harvested; and it makes a wine with silky tannins.

“Our wines don’t make themselves. Every decision has to be made,” explained Hampson, “and non-intervention is for marketing (departments) only.

“I don’t want to confuse people with ‘wines of place’ and ‘wines of technique’… But a lot of it is learning the place. More subtle wines demand more aggressive handling, made through practical decisions.

“We make wines through personality (of the place).”

~ Alan Goldfarb, Napa Editor

To comment on Alan Goldfarb’s writings and thoughts, contact him at a.goldfarb@appellationamerica.com