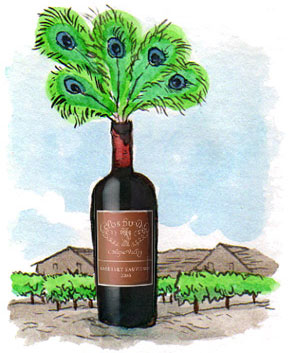

Clos du Val's Bernard Portet refers to the finish of a great wine as its "peacock tail".

Stags Leap District ~ Napa Valley (AVA)

Bernard Portet of Clos du Val: Evolution of the CDV style

"We’re evolving. We’re trying to combine, and it’s difficult, the elegance and balance of the wine with user friendliness."

by

Alan Goldfarb

October 4, 2006

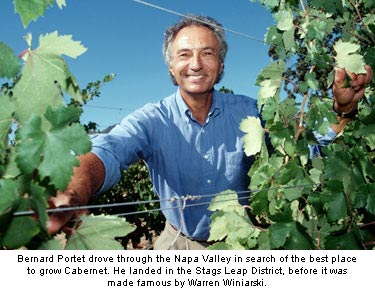

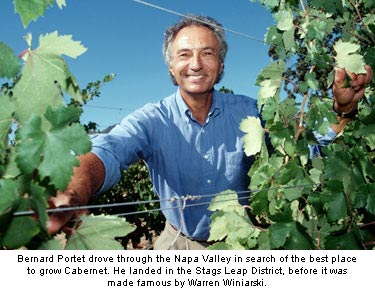

Alan Goldfarb (AG): Many people tell me that the reason they opened a winery in Stags Leap was because of Warren Winiarski and the fact that he won the Paris Tasting. It made them feel that the area must produce great wine. But you were already there at the same time as Warren, so what led you to decide to open in Stags Leap?

Bernard Portet (BP): My approach was very different from the local approach back then. Because I was raised in Bordeaux, I looked at those types of wines. Terroir is the most important thing, so when I looked around the world, I looked at places that would be conducive to Cabernet Sauvignon.

Terroir was part of the thought from the beginning.

The first time I came to the U.S. in 1968, I thought there were some great wines made in the mid-valley, in Rutherford, but I found the climate a bit hot for my French palate.

The first time I came to the U.S. in 1968, I thought there were some great wines made in the mid-valley, in Rutherford, but I found the climate a bit hot for my French palate.

I remember going down the Silverado Trail in summer, all of a sudden, the climate was cooler there, with cooler nights, and I liked that. The winds were always coming from the southwest during the summer.

That cooling breeze makes the difference. When I saw that cool climate, I thought that it would make fresher, tastier wines. The wines would be less lean and more velvety, and I like that a lot.

AG: We know that the heat is generated off the rock formation -- the Palisades -- on the east side of the Trail in the Vaca Range. Is it really that much of an influence?

BP: It also funnels the wind, makes it accelerate a little bit and it cools more. I believe this also happens in the hills on the west side of the trail, (such as Wappo Hill, where Michael and Robert Mondavi live) where the wind rolls over and funnels the air, too.

AG: Who is John Goelet, who started Clos du Val with you? Not much is known about him in the Napa Valley.

BP: We met in 1970. He’s an absentee owner from New York whose mother was connected to Barton & Guestier (primarily a French wine company). He’s a Guestier. But he was born in the Southwest of France. He asked me to find a place anywhere in the world where I thought we could grow top quality grapes.

AG: Your wines always seem to be among the longest lived from the Napa Valley. How come, after all the years of making wines like that, you seem to have acquiesced to the market that demands readily accessible wines? Was it because of your Bordeaux background that you kept at it for so long?

BP: My Bordeaux background definitely had much to do with that. The wines were austere, there’s no doubt about that. I was lucky to be raised by my father in a Bordeaux chateau. Also, my mother used to say that there are very few balanced and elegant wines with complexity that have a long finish. That’s the way Europeans talk about it, but not how others talk about it.

We call the finish the “peacock tail.”

AG: I’ve heard of that, but I’m not sure what you mean.

BP: Many people believe it’s the persistence of the initial impression. But the persistence is most often at the top of the palate. The long finish that I’m talking about is that the fresh fruit sits on the back of the tongue and keeps coming back and expresses the peacock tail. The tail is fanned out like a peacock and is more elegant than a turkey.

AG: That’s a subtle explanation. I’ve always described the “finish” as the taste that lingers on the palate.

BP: Yes, but it’s very different as far as I’m concerned. The lingering is not only the flavors but the weight and the density, the volume and the flesh. There are some years when you can achieve that and some when you can’t.

AG: It may be easy for you to understand why you can't make a wine like that every year, but can you try to explain it for the rest of us?

BP: There are vintages (differences) in California, if you respect the balance of the terroir. Some years produce softer wines, and there are other years that are more aggressive. You will not see that over-aggressiveness at Clos du Val. We want a Merlot to taste like a Merlot. (See Alan Goldfarb’s review of the 2003 CDV Merlot)

BP: There are vintages (differences) in California, if you respect the balance of the terroir. Some years produce softer wines, and there are other years that are more aggressive. You will not see that over-aggressiveness at Clos du Val. We want a Merlot to taste like a Merlot. (See Alan Goldfarb’s review of the 2003 CDV Merlot)

AG: It’s apparent to me why you want to achieve a long finish, but explain why you want to attain that softer characteristic.

BP: Those types of wines go better with food. The wines are less explosive in front. The food and wine is more important than the explosion. Most wines that express themselves in the finish are not as aggressive. They’re more austere, more restrained but they go very well with food, and I like that. As the flavors of the food melt away, the flavors of the wine take over.

AG: There is a large segment of the American population that prefers wines that explode in the mouth; and they could give a fig if it goes with their food.

BP: Yes, there are plenty of people who like that style. And in the past 7-10 years, we’ve paid much more attention to the fruit. We’ve been trying to make them user friendly, less austere with more roundness.

We're evolving. We're trying to combine the elegance and balance of the wine with user friendliness. It's a difficult thing to do.

AG: I’m guessing that that goes against your grain.

BP: Not anymore (laughing). There’s no need for me to make a wine that doesn’t sell. It took me -- us -- some time to evolve in that direction.

AG: Who made the decision?

BP: The market. It said your wines are too reserved. And the board of directors also.

It’s not only the concept, but then, we had to learn how to make it. We were replanting our vineyards and we were dealing with younger vines. We harvest now slightly riper. Our wines are a bit more chewy now, fresher and fruitier. But as our vines age, our wines will have much more depth and a higher level of complexity.

AG: What was John Clew’s influence?

BP: It was a good influence. The reason why John Clews joined us was for Chardonnay and Pinot Noir (from the

Bernard Portet (BP): My approach was very different from the local approach back then. Because I was raised in Bordeaux, I looked at those types of wines. Terroir is the most important thing, so when I looked around the world, I looked at places that would be conducive to Cabernet Sauvignon.

Terroir was part of the thought from the beginning.

The first time I came to the U.S. in 1968, I thought there were some great wines made in the mid-valley, in Rutherford, but I found the climate a bit hot for my French palate.

The first time I came to the U.S. in 1968, I thought there were some great wines made in the mid-valley, in Rutherford, but I found the climate a bit hot for my French palate.I remember going down the Silverado Trail in summer, all of a sudden, the climate was cooler there, with cooler nights, and I liked that. The winds were always coming from the southwest during the summer.

That cooling breeze makes the difference. When I saw that cool climate, I thought that it would make fresher, tastier wines. The wines would be less lean and more velvety, and I like that a lot.

AG: We know that the heat is generated off the rock formation -- the Palisades -- on the east side of the Trail in the Vaca Range. Is it really that much of an influence?

BP: It also funnels the wind, makes it accelerate a little bit and it cools more. I believe this also happens in the hills on the west side of the trail, (such as Wappo Hill, where Michael and Robert Mondavi live) where the wind rolls over and funnels the air, too.

AG: Who is John Goelet, who started Clos du Val with you? Not much is known about him in the Napa Valley.

BP: We met in 1970. He’s an absentee owner from New York whose mother was connected to Barton & Guestier (primarily a French wine company). He’s a Guestier. But he was born in the Southwest of France. He asked me to find a place anywhere in the world where I thought we could grow top quality grapes.

AG: Your wines always seem to be among the longest lived from the Napa Valley. How come, after all the years of making wines like that, you seem to have acquiesced to the market that demands readily accessible wines? Was it because of your Bordeaux background that you kept at it for so long?

BP: My Bordeaux background definitely had much to do with that. The wines were austere, there’s no doubt about that. I was lucky to be raised by my father in a Bordeaux chateau. Also, my mother used to say that there are very few balanced and elegant wines with complexity that have a long finish. That’s the way Europeans talk about it, but not how others talk about it.

We call the finish the “peacock tail.”

AG: I’ve heard of that, but I’m not sure what you mean.

BP: Many people believe it’s the persistence of the initial impression. But the persistence is most often at the top of the palate. The long finish that I’m talking about is that the fresh fruit sits on the back of the tongue and keeps coming back and expresses the peacock tail. The tail is fanned out like a peacock and is more elegant than a turkey.

AG: That’s a subtle explanation. I’ve always described the “finish” as the taste that lingers on the palate.

BP: Yes, but it’s very different as far as I’m concerned. The lingering is not only the flavors but the weight and the density, the volume and the flesh. There are some years when you can achieve that and some when you can’t.

AG: It may be easy for you to understand why you can't make a wine like that every year, but can you try to explain it for the rest of us?

BP: There are vintages (differences) in California, if you respect the balance of the terroir. Some years produce softer wines, and there are other years that are more aggressive. You will not see that over-aggressiveness at Clos du Val. We want a Merlot to taste like a Merlot. (See Alan Goldfarb’s review of the 2003 CDV Merlot)

BP: There are vintages (differences) in California, if you respect the balance of the terroir. Some years produce softer wines, and there are other years that are more aggressive. You will not see that over-aggressiveness at Clos du Val. We want a Merlot to taste like a Merlot. (See Alan Goldfarb’s review of the 2003 CDV Merlot)AG: It’s apparent to me why you want to achieve a long finish, but explain why you want to attain that softer characteristic.

BP: Those types of wines go better with food. The wines are less explosive in front. The food and wine is more important than the explosion. Most wines that express themselves in the finish are not as aggressive. They’re more austere, more restrained but they go very well with food, and I like that. As the flavors of the food melt away, the flavors of the wine take over.

AG: There is a large segment of the American population that prefers wines that explode in the mouth; and they could give a fig if it goes with their food.

BP: Yes, there are plenty of people who like that style. And in the past 7-10 years, we’ve paid much more attention to the fruit. We’ve been trying to make them user friendly, less austere with more roundness.

We're evolving. We're trying to combine the elegance and balance of the wine with user friendliness. It's a difficult thing to do.

AG: I’m guessing that that goes against your grain.

BP: Not anymore (laughing). There’s no need for me to make a wine that doesn’t sell. It took me -- us -- some time to evolve in that direction.

AG: Who made the decision?

BP: The market. It said your wines are too reserved. And the board of directors also.

It’s not only the concept, but then, we had to learn how to make it. We were replanting our vineyards and we were dealing with younger vines. We harvest now slightly riper. Our wines are a bit more chewy now, fresher and fruitier. But as our vines age, our wines will have much more depth and a higher level of complexity.

AG: What was John Clew’s influence?

BP: It was a good influence. The reason why John Clews joined us was for Chardonnay and Pinot Noir (from the

Print this article | Email this article | More about Stags Leap District ~ Napa Valley | More from Alan Goldfarb