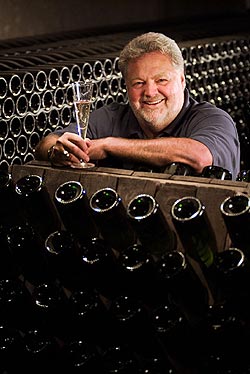

Reflections on Okanagan wine growing by Harry McWatters, founder of Sumac Ridge Estate Winery

With the Okanagan's lack of rainfall, the abundance of sunshine and the light intensity, we should be able to grow everything. And we try.

by

John Schreiner

May 4, 2005

McWatters: When I started in the business, we only had two consumers: those that took it out of the brown paper bags and those that didn’t. One thing that is the most constant in the wine industry – I have 38 vintages behind me in the business – is that we are market-driven. It is the wineries that listen to what the customers want that will be amongst the most successful.

Baby Duck

You must know that there were a handful of consumers that really wanted a product like Baby Duck, and a lot of other wines like it. [Baby Duck, a pink sparkling wine with seven per cent alcohol, was created in 1971 in British Columbia by Andrés Wines Ltd.]

As much as people chuckle about it today, it is evident that that style of wine introduced an awful lot of folks to the idea of drinking wine. People who grew up in Canada drank soft drinks in their youth -- sweet cold bubbly beverages. So a transitional step from drinking that to something that might be actually be made of grapes, the Baby Duck style of wines, was a pretty natural progression. It was sweet, cold and bubbly – and sometimes had grapes in it. As much as nobody admitted to drinking it, it was the largest selling alcoholic beverage in this country for five consecutive years.

I shouldn’t pick on Baby Duck because it is an easy target. There were lots of other products like it that were sweet, cold and bubbly and were named after ducks or bears or geese. I usually call that the zoology stage of the wine industry in Canada.

other products like it that were sweet, cold and bubbly and were named after ducks or bears or geese. I usually call that the zoology stage of the wine industry in Canada.

From there, it was pretty easy to progress to still wines that were fruity, that were served cold, tended to be lighter in alcohol. A lot of them tended to be German imitators. A lot of those are still in the market and become great introductions to the idea of drinking wine.

To go from there to the next step, to wines that were not necessarily German imitators but were either German wines or wines that were produced in British Columbia from Germanic styles of grapes was a pretty easy transition. We really built the first credible industry for British Columbia grown wines based on that Germanic characteristic.

Becker Project

The Becker Project was influenced not only from the market but from the production side. Two major plantings in the Okanagan were planted [under the direction of] Dr. Helmut Becker of the Geisenheim Institute. He planted just a plethora of different grape varieties to see how they would do here. It was a great experiment for him and it was a great experiment for us. [The so-called Becker Project ran from 1977 to 1985 and evaluated a large number of vinifera varieties, many of which were then picked up by growers.]

We are still trying to overcome some of the varieties that were grown. It wasn’t that they were not good. But we are often asked in other regions of the world why we grow such a wide, wide range of varieties. We have things like Optima, Ortega, Bacchus, Oraniensteiner, Rkatsitelli, Matsvani, Ehrenfelser … and the list just goes on. All of them make some wonderful wines. It is not where we have evolved to.

But they were great stepping stones for two reasons. One, they embraced the palate of the consumer of the day. And two, they proved to us and the world that we could actually grow and mature Vitis vinifera vines. This really puzzles people in other parts of the world: how do we do what we do?

Frequently, I will be in the winery, talking to Vancouver and being asked what all the rain is doing to the grapes. And I will look out the window and ask, “What rain?”

Okanagan Valley

Ninety-five per cent of British Columbia’s grapes are grown in the Okanagan Valley. It is more than 100 miles from the U.S. border to the northern extremity. There are several mountain ranges in British Columbia and the Okanagan sits in the middle of the province. The south Okanagan is 400 miles due east of Vancouver. [The mountain ranges block the Pacific rains from reaching the Okanagan.]

At our Black Sage vineyard, where some of our wines come from, the average rainfall over the last 30 years is six inches a year. In some years, we fall dramatically below that. We can’t grow grapes in the Okanagan Valley without irrigation. That’s one fact.

Another thing that surprises people is that we get more hours of sunlight than any other region – not any other grape-growing region but any other place – in North America. When you go to Hawaii, it gets dark about six o’clock. On the 21st of June, we don’t get dark until 10 or 11 o’clock at night. So we only get three or four hours of total darkness. And the nice thing about getting a lot of sunlight is that it happens during the growing season!

The other factor is that we get greater light intensity. This is not a McWatters theory but one pointed out by Dr. Richard Smart, an internationally renowned viticulturist who measures light intensity in vineyards around the world. He says we get more light intensity than any other grape growing region in the world.

With this lack of rainfall, the abundance of sunshine and the light intensity, we should be able to grow everything. And we try.

Light intensity

Question: Can you clarify light intensity?

McWatters: It is a measurement of the intensity with which the sunlight hits the surface of the leaf.

Question: Does our geographical position [in the northern hemisphere] contribute to it?

McWatters: Yes. Obviously, the profile of the vineyard is going to assist that. But if you have air pollution and cloud cover, the sun won’t get there to start with. Lack of air pollution is a big part of the Okanagan advantage.

More than what light intensity is, what does it do? It generates photosynthesis and that develops the plants. We are not actually in the business of growing grape vines, we are in the business of growing grapes. So the importance of light intensity is what it does to the fruit that is on that vine.

I believe that this is what is contributing to the complexity and the layers of flavour that we are able to develop. Not by itself, of course, but it is a major contributing factor.

Quality also comes down to clonal selection, site selection, the variety itself, rootstocks, and a multiple of other things that will add to getting us to maturity of the grape.

[The geographic position] of our region gives us ripeness in most varieties in most years, as long as good site selection has been a major consideration. Along with that ripeness, we still maintain abundant natural acidity. Sometimes, we get pretty assertive acids in some varieties in some locations in some years; so it is a matter sometimes of taming that.

Having said that, it also is what makes our wines a little more approachable with food than so many other regions. It helps develop the personality of the region.

Question: Can you give more detail on the extent of the Okanagan Valley?

McWatters: The appellation itself is defined by the watershed, which is basically from the peaks of the mountain ranges on either side; and from the U.S. border to just north of Vernon, the north end of the Okanagan watershed.

If you take the lake itself, the lake is 87 miles long – it does not cover our total region – and it is five miles wide at the widest point. The lake onl

Baby Duck

You must know that there were a handful of consumers that really wanted a product like Baby Duck, and a lot of other wines like it. [Baby Duck, a pink sparkling wine with seven per cent alcohol, was created in 1971 in British Columbia by Andrés Wines Ltd.]

As much as people chuckle about it today, it is evident that that style of wine introduced an awful lot of folks to the idea of drinking wine. People who grew up in Canada drank soft drinks in their youth -- sweet cold bubbly beverages. So a transitional step from drinking that to something that might be actually be made of grapes, the Baby Duck style of wines, was a pretty natural progression. It was sweet, cold and bubbly – and sometimes had grapes in it. As much as nobody admitted to drinking it, it was the largest selling alcoholic beverage in this country for five consecutive years.

I shouldn’t pick on Baby Duck because it is an easy target. There were lots of

other products like it that were sweet, cold and bubbly and were named after ducks or bears or geese. I usually call that the zoology stage of the wine industry in Canada.

other products like it that were sweet, cold and bubbly and were named after ducks or bears or geese. I usually call that the zoology stage of the wine industry in Canada.

From there, it was pretty easy to progress to still wines that were fruity, that were served cold, tended to be lighter in alcohol. A lot of them tended to be German imitators. A lot of those are still in the market and become great introductions to the idea of drinking wine.

To go from there to the next step, to wines that were not necessarily German imitators but were either German wines or wines that were produced in British Columbia from Germanic styles of grapes was a pretty easy transition. We really built the first credible industry for British Columbia grown wines based on that Germanic characteristic.

Becker Project

The Becker Project was influenced not only from the market but from the production side. Two major plantings in the Okanagan were planted [under the direction of] Dr. Helmut Becker of the Geisenheim Institute. He planted just a plethora of different grape varieties to see how they would do here. It was a great experiment for him and it was a great experiment for us. [The so-called Becker Project ran from 1977 to 1985 and evaluated a large number of vinifera varieties, many of which were then picked up by growers.]

We are still trying to overcome some of the varieties that were grown. It wasn’t that they were not good. But we are often asked in other regions of the world why we grow such a wide, wide range of varieties. We have things like Optima, Ortega, Bacchus, Oraniensteiner, Rkatsitelli, Matsvani, Ehrenfelser … and the list just goes on. All of them make some wonderful wines. It is not where we have evolved to.

But they were great stepping stones for two reasons. One, they embraced the palate of the consumer of the day. And two, they proved to us and the world that we could actually grow and mature Vitis vinifera vines. This really puzzles people in other parts of the world: how do we do what we do?

Frequently, I will be in the winery, talking to Vancouver and being asked what all the rain is doing to the grapes. And I will look out the window and ask, “What rain?”

Okanagan Valley

Ninety-five per cent of British Columbia’s grapes are grown in the Okanagan Valley. It is more than 100 miles from the U.S. border to the northern extremity. There are several mountain ranges in British Columbia and the Okanagan sits in the middle of the province. The south Okanagan is 400 miles due east of Vancouver. [The mountain ranges block the Pacific rains from reaching the Okanagan.]

At our Black Sage vineyard, where some of our wines come from, the average rainfall over the last 30 years is six inches a year. In some years, we fall dramatically below that. We can’t grow grapes in the Okanagan Valley without irrigation. That’s one fact.

Another thing that surprises people is that we get more hours of sunlight than any other region – not any other grape-growing region but any other place – in North America. When you go to Hawaii, it gets dark about six o’clock. On the 21st of June, we don’t get dark until 10 or 11 o’clock at night. So we only get three or four hours of total darkness. And the nice thing about getting a lot of sunlight is that it happens during the growing season!

The other factor is that we get greater light intensity. This is not a McWatters theory but one pointed out by Dr. Richard Smart, an internationally renowned viticulturist who measures light intensity in vineyards around the world. He says we get more light intensity than any other grape growing region in the world.

With this lack of rainfall, the abundance of sunshine and the light intensity, we should be able to grow everything. And we try.

Light intensity

Question: Can you clarify light intensity?

McWatters: It is a measurement of the intensity with which the sunlight hits the surface of the leaf.

Question: Does our geographical position [in the northern hemisphere] contribute to it?

McWatters: Yes. Obviously, the profile of the vineyard is going to assist that. But if you have air pollution and cloud cover, the sun won’t get there to start with. Lack of air pollution is a big part of the Okanagan advantage.

More than what light intensity is, what does it do? It generates photosynthesis and that develops the plants. We are not actually in the business of growing grape vines, we are in the business of growing grapes. So the importance of light intensity is what it does to the fruit that is on that vine.

I believe that this is what is contributing to the complexity and the layers of flavour that we are able to develop. Not by itself, of course, but it is a major contributing factor.

Quality also comes down to clonal selection, site selection, the variety itself, rootstocks, and a multiple of other things that will add to getting us to maturity of the grape.

[The geographic position] of our region gives us ripeness in most varieties in most years, as long as good site selection has been a major consideration. Along with that ripeness, we still maintain abundant natural acidity. Sometimes, we get pretty assertive acids in some varieties in some locations in some years; so it is a matter sometimes of taming that.

Having said that, it also is what makes our wines a little more approachable with food than so many other regions. It helps develop the personality of the region.

Question: Can you give more detail on the extent of the Okanagan Valley?

McWatters: The appellation itself is defined by the watershed, which is basically from the peaks of the mountain ranges on either side; and from the U.S. border to just north of Vernon, the north end of the Okanagan watershed.

If you take the lake itself, the lake is 87 miles long – it does not cover our total region – and it is five miles wide at the widest point. The lake onl