Lee Hudson protects the name and highly regarded reputation of his Carneros vineyard by trademarking it.

Trademarked Vineyards

A hedge against the devaluation

of “Vineyard Designates”

by

Alan Goldfarb

May 17, 2007

Are “vineyard designated” wines destined to meet a similar fate? Can anyone put a vineyard name on a label and call it special? What about the quality of the grapes themselves? Do they have to be the best?

The consumer, quite naturally, may assume that those marked with an individual vineyard name, should be a wine of a certain quality. But because vineyard-designates are becoming de rigueur, the term “vineyard-designate” may soon also be degraded.

Lee Hudson is one grape grower who has gone beyond vineyard designation in order to add meaning to the term, to ensure that those who use his grapes make wines of distinction, and to protect his good name.

Hudson, who has a renowned 160-acre parcel on the Napa side of the Carneros region, has trademarked his vineyard and issues licenses to his clients who put Hudson Vineyards on their labels. The vineyard itself is located west of the once-famed Winery Lake Vineyard, and across from Domaine Carneros.

Lee Hudson sports a trademarked image.

Carneros, trademarked their land in 1989. Rochioli Vineyards in the Russian River area is also trademarked. The Napa Valley Vintners began a program in 2003 to certify that wines marked with its symbol – much like the gallo or rooster in Chianti – assured that 100 percent of the grapes in that bottle came from the Napa Valley.

So too has Lee Hudson deigned to protect himself. “I had to protect my name because otherwise, I’d lose my only asset – my reputation,” Hudson says as he explains why he chose to trademark his vineyard. “Technically, Hudson Vineyards is a vineyard designate, but I view it as a brand.”

Hudson has about 32 wineries that use his grapes – mostly Chardonnay and Syrah, along with Pinot Noir, Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Grenache, Pinot Gris and Viognier. But he has a few producers [13] with whom he’s established long-term contracts to sell them select blocks.

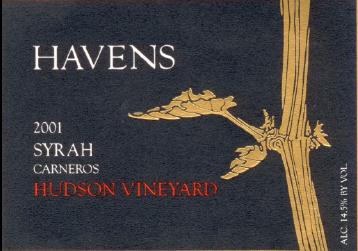

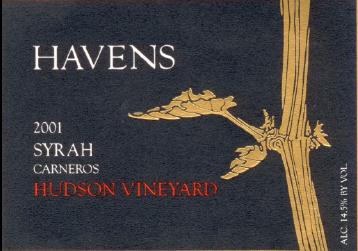

For $1 (he says the purpose of the license is not to produce revenue), he will allow the likes of Havens, Kongsgaard, Lewis, and Nickel & Nickel to purchase specific blocks of Syrah. Kistler and Patz & Hall purchase site-specific Chardonnay from him, and Arietta uses a block of his Merlot and Cab Franc. These sites, Hudson believes, are worthy of the name Hudson Vineyards on those labels.

“My (block-designated) wines are real, but there’s a degradation going on because there are so many,” he says. “When you look at it from a European perspective, it’s (trademarking and licensing) defining a specific subset of a larger vineyard, defined by soil, exposure, climate, rootstock, clone, scion, management, and winemaker.”

Hudson refuses to use the word “terroir” to define his vineyard because “that’s a French term.” He prefers instead to use the phrase, “site-driven.”

“It’s not necessarily better but soil, climate, rootstock, clone, scion, management, and winemaker are in fact indicative of that location. Those wines have a tendency to be of great importance and interest. … These are sites of intense, interesting, varietal distinctiveness.

“…Often times it’s concentration, other times it’s finesse, or extraction. … Often times they’re similar to their counterparts in Europe.

“The site’s the driver. It’s the sweet spot. It’s the site, stupid. It’s the difference between good and incredible wine. It’s got very little to do with me. I manage all our vineyards the same way. Some (blocks) seem to consistently jump out. Even in bad years, those sites seem to rise above the medium.”

In his agreement with his clients, Hudson also reserves the right to ensure that those grapes being used from those blocks are indeed worthy of their designated labeling.

“I have to have a long-term relationship (with his clients) and the wines have to be, in the long-term, proven to both of us so that it proves the site, the uniqueness of the site,” he says.

“They have because they felt the wine didn’t live up to their consumers’ expectations. Those are the kinds of clients I want to work with,” he says. “… It’s not a perfect world. What they’re saying is, ‘We have been making wine for 5-10 years out of this block and our consumers have grown to expect a certain wine out of this block. This (wine) is so atypical it would be confusing and upsetting to our consumer.’

saying is, ‘We have been making wine for 5-10 years out of this block and our consumers have grown to expect a certain wine out of this block. This (wine) is so atypical it would be confusing and upsetting to our consumer.’

“If people are going to use my name, I want to make sure they would, if necessary, declassify. They might simply call it an ‘appellation wine’ (from Carneros), and take it (the block designation) down one.

“Vineyard designated wines are a notch up in sense of refinement, and they should be because you’re zeroing in very specific locations. The definition doesn’t require high-site specificity. It only requires that grapes come from that vineyard.”

Hudson says producers come to him all the time to buy grapes from those specific sites, but he tells them, “I have no more. I haven’t discovered any more (on my land).” He’ll sell you grapes from other areas of his vineyard, but those will simply have to be designated “Carneros.”

But it’s those precious few, trademarked blocks that he’s betting on as a means to add meaning to the intent of a vineyard-designated wine. “

The consumer, quite naturally, may assume that those marked with an individual vineyard name, should be a wine of a certain quality. But because vineyard-designates are becoming de rigueur, the term “vineyard-designate” may soon also be degraded.

Lee Hudson is one grape grower who has gone beyond vineyard designation in order to add meaning to the term, to ensure that those who use his grapes make wines of distinction, and to protect his good name.

Hudson, who has a renowned 160-acre parcel on the Napa side of the Carneros region, has trademarked his vineyard and issues licenses to his clients who put Hudson Vineyards on their labels. The vineyard itself is located west of the once-famed Winery Lake Vineyard, and across from Domaine Carneros.

Regarding the Vineyard as a Product

The practice of trademarked vineyards is not a new one. Hudson officially credentialed his vineyard in the mid-‘90s, while the Sangiacomo family of Sonoma County, who have about 1,000 acres, most of which are also in the

Lee Hudson sports a trademarked image.

So too has Lee Hudson deigned to protect himself. “I had to protect my name because otherwise, I’d lose my only asset – my reputation,” Hudson says as he explains why he chose to trademark his vineyard. “Technically, Hudson Vineyards is a vineyard designate, but I view it as a brand.”

Hudson has about 32 wineries that use his grapes – mostly Chardonnay and Syrah, along with Pinot Noir, Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Grenache, Pinot Gris and Viognier. But he has a few producers [13] with whom he’s established long-term contracts to sell them select blocks.

For $1 (he says the purpose of the license is not to produce revenue), he will allow the likes of Havens, Kongsgaard, Lewis, and Nickel & Nickel to purchase specific blocks of Syrah. Kistler and Patz & Hall purchase site-specific Chardonnay from him, and Arietta uses a block of his Merlot and Cab Franc. These sites, Hudson believes, are worthy of the name Hudson Vineyards on those labels.

“My (block-designated) wines are real, but there’s a degradation going on because there are so many,” he says. “When you look at it from a European perspective, it’s (trademarking and licensing) defining a specific subset of a larger vineyard, defined by soil, exposure, climate, rootstock, clone, scion, management, and winemaker.”

Hudson refuses to use the word “terroir” to define his vineyard because “that’s a French term.” He prefers instead to use the phrase, “site-driven.”

“It’s not necessarily better but soil, climate, rootstock, clone, scion, management, and winemaker are in fact indicative of that location. Those wines have a tendency to be of great importance and interest. … These are sites of intense, interesting, varietal distinctiveness.

“…Often times it’s concentration, other times it’s finesse, or extraction. … Often times they’re similar to their counterparts in Europe.

“The site’s the driver. It’s the sweet spot. It’s the site, stupid. It’s the difference between good and incredible wine. It’s got very little to do with me. I manage all our vineyards the same way. Some (blocks) seem to consistently jump out. Even in bad years, those sites seem to rise above the medium.”

In his agreement with his clients, Hudson also reserves the right to ensure that those grapes being used from those blocks are indeed worthy of their designated labeling.

“I have to have a long-term relationship (with his clients) and the wines have to be, in the long-term, proven to both of us so that it proves the site, the uniqueness of the site,” he says.

The Wine from the Vineyard Requires Approval First

Toward that end, he has the right to taste and review the wines to make sure they are up to his standards – as well as the criteria of the producers themselves. He has never declassified a wine or deemed it unsuitable to use his name. But he insists that his clients have the right to do that themselves – and they have.“They have because they felt the wine didn’t live up to their consumers’ expectations. Those are the kinds of clients I want to work with,” he says. “… It’s not a perfect world. What they’re

saying is, ‘We have been making wine for 5-10 years out of this block and our consumers have grown to expect a certain wine out of this block. This (wine) is so atypical it would be confusing and upsetting to our consumer.’

saying is, ‘We have been making wine for 5-10 years out of this block and our consumers have grown to expect a certain wine out of this block. This (wine) is so atypical it would be confusing and upsetting to our consumer.’

“If people are going to use my name, I want to make sure they would, if necessary, declassify. They might simply call it an ‘appellation wine’ (from Carneros), and take it (the block designation) down one.

“Vineyard designated wines are a notch up in sense of refinement, and they should be because you’re zeroing in very specific locations. The definition doesn’t require high-site specificity. It only requires that grapes come from that vineyard.”

Hudson says producers come to him all the time to buy grapes from those specific sites, but he tells them, “I have no more. I haven’t discovered any more (on my land).” He’ll sell you grapes from other areas of his vineyard, but those will simply have to be designated “Carneros.”

But it’s those precious few, trademarked blocks that he’s betting on as a means to add meaning to the intent of a vineyard-designated wine. “

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,