While the much publicized Westside enjoys the limelight, there is a great debate within Paso Robles about the relevancy of creating a new appellation using a Highway as the dividing line.

East versus West: The great Paso Robles rift

"The division as proposed is probably too broad, but it’s better than nothing at all."~ Justin Baldwin, proprietor Justin Vineyards & Winery

by

Mary Baker

October 17, 2006

Mary Baker (MB): What are the geographical/terrain differences between the Paso Robles East and West regions?

Shannon O’Neill (SO): The differences are great. The West side is mountainous and the East is mostly rolling hills and plains.

Justin Baldwin (JB): Yes, the West has higher elevations, steep hillsides, proximity to the ocean, absence of agua, and wooded terrain.

MB: What are the soil differences?

MB: What are the soil differences?

JB: The West has varied soils with high calcareous concentrations, high Ph’s, low fertility, and chemically bound up nutrients. The soils in the West are highly fractured, with lots of clay to absorb and retain water; they’re multi-layered and varied.

SO: But, even without getting into technical makeup of the soils, you can see that they are very different. The West side soils are more nutrient rich than the alluvial soil of the East side. The East side soils are more loam and clay loam, and are more nutrient deficient than the West side soils. What I found most interesting though, is the new revelation put forth by UC Davis soil researcher Debra Elliot Fisk, who is doing the Appellation study for the TTB. She says that there is no limestone anywhere in the Paso Robles appellation, especially on the West side.

This was interesting to me because for years the West side has been hyping its soils as limestone, and comparing it to the great vineyards in France. All that time, the mainstream wine media sucked it all down and regurgitated it in their articles as a reason for West side superiority over the East side. Gary Eberle has been saying for years that the supposed limestone is only mudstone. I am not a soil scientist but I sure hope it’s true.

Gary Eberle (GE): Well, I created the Paso Robles appellation in 1983 and did a lot of work on the soils and climate. I have also been making wine from vineyards all over the area.

Gary Eberle (GE): Well, I created the Paso Robles appellation in 1983 and did a lot of work on the soils and climate. I have also been making wine from vineyards all over the area.

Having said, that, your article Paso Robles, A Linguistic Geography of Wine is incorrect in that there is essentially no "limestone" in this area. There is a tiny outcropping in the extreme West side of San Luis Obispo County, but I believe it lies entirely outside of the Paso Robles appellation. We do have an abundance of "mudstone" which is entirely different than limestone. Limestone is calcium carbonate, and mudstone is calcium silicates. They are completely different in their properties and how they contribute to the terroir.

MB: What about the meteorological differences between East & West?

SO: The West side has 40+ inches of rain per year and the East side has only 12 inches per year. During the summer growing season, the daytime temperature of the West is considerably less than that of the East. Sometimes 10 to 15 degrees cooler.

GE: And these factors make a big difference. If you look at the soils and vegetation on the two sides, you cannot doubt where the fertile soils are. All the truck farming is on the West side. The East side cannot even grow poison oak, yet it is all over the West. The tremendous difference in rainfall between the two areas has a lot to do with this. The large rainfall on the hills to the West allows a lot more natural vegetation to grow and as it decomposes, it creates deep and fertile soils.

The East side does not get enough rain, and our soils are so open that until we found out how to bring up the deep water under this area, growing grapes, vegetables, or any thing else was not possible. Back then, this area was used for dry-farmed barley, and grazing cattle on poverty grass.

JB: So, in a nutshell, the West has double or higher rainfall than the East, cooler daytime highs and nighttime lows, marine and coastal mountain influences, and more stars . . . (laughs)!

MB: Perhaps you could each talk about where you are located and why you chose that specific location?

GE: I did my doctoral work at UC Davis with a major in fermentation science and a minor in viticulture. During my last year at Davis I made three trips to Paso Robles with Drs. Olmo and Alley, and with Jack Foote, who was the local farm advisor here at that time. We dug holes in multiple locations in what is now the Paso appellation, and took soils back to the soil science lab for analysis. It was the results of these reports and meteorological investigations that made me choose the location where I planted my vineyards.

The other major factor in my choice of the East side is that, for the most part, the soils are remarkably infertile. I decided to stay on the infertile soils as the Europeans have learned to do over the centuries when it comes to locating vineyards. Grapes have the ability to reach deep into the soil for their needs. You want the grapes to go deep. Don't grow them on fertile and heavy soils where they stay close to the surface.

SO: I can’t say I really chose one side over the other. We have one vineyard located on Union Road and one located on Creston Road. We also farm and make wine from a vineyard on Adelaida Road and source fruit from all over the West and East side as well as San Miguel, Indian Valley, and Monterey.

I chose the East locations for their unique microclimates, terroirs, and proximity to other premium vineyards producing high quality wines. I like to produce big extracted reds, which are more suited to East side vineyards. I chose the West side vineyard because of the ability to dry farm it, and for its old head-trained Zinfandel, which is more suited to the West side.

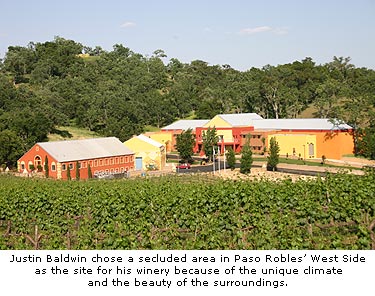

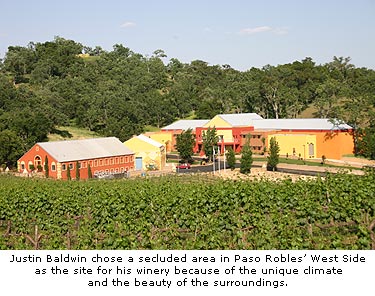

JB: Our site is the most northerly, highest in elevation, and furthest West of all the wineries and vineyards in our AVA. We chose the location because it’s beautiful, and for the soils, the southern slope, the amount of water available from our wells, the fact that nobody had ever planted grapes nearby, and because most of the land around me is in large parcels owned by the original Mennonite settlers. Even today there are less than 100 parcels in the 100 square miles surrounding my property.

JB: Our site is the most northerly, highest in elevation, and furthest West of all the wineries and vineyards in our AVA. We chose the location because it’s beautiful, and for the soils, the southern slope, the amount of water available from our wells, the fact that nobody had ever planted grapes nearby, and because most of the land around me is in large parcels owned by the original Mennonite settlers. Even today there are less than 100 parcels in the 100 square miles surrounding my property.

MB: Do you think the two subregions have similar ‘Paso Robles’ taste characteristics? If so, what are they?

SO: No, the East side has more big, fruit driven wines that can accumulate higher sugars and more extracted flavors. The West side has more spicy, mineral type

Shannon O’Neill (SO): The differences are great. The West side is mountainous and the East is mostly rolling hills and plains.

Justin Baldwin (JB): Yes, the West has higher elevations, steep hillsides, proximity to the ocean, absence of agua, and wooded terrain.

MB: What are the soil differences?

MB: What are the soil differences?JB: The West has varied soils with high calcareous concentrations, high Ph’s, low fertility, and chemically bound up nutrients. The soils in the West are highly fractured, with lots of clay to absorb and retain water; they’re multi-layered and varied.

SO: But, even without getting into technical makeup of the soils, you can see that they are very different. The West side soils are more nutrient rich than the alluvial soil of the East side. The East side soils are more loam and clay loam, and are more nutrient deficient than the West side soils. What I found most interesting though, is the new revelation put forth by UC Davis soil researcher Debra Elliot Fisk, who is doing the Appellation study for the TTB. She says that there is no limestone anywhere in the Paso Robles appellation, especially on the West side.

This was interesting to me because for years the West side has been hyping its soils as limestone, and comparing it to the great vineyards in France. All that time, the mainstream wine media sucked it all down and regurgitated it in their articles as a reason for West side superiority over the East side. Gary Eberle has been saying for years that the supposed limestone is only mudstone. I am not a soil scientist but I sure hope it’s true.

Gary Eberle (GE): Well, I created the Paso Robles appellation in 1983 and did a lot of work on the soils and climate. I have also been making wine from vineyards all over the area.

Gary Eberle (GE): Well, I created the Paso Robles appellation in 1983 and did a lot of work on the soils and climate. I have also been making wine from vineyards all over the area.Having said, that, your article Paso Robles, A Linguistic Geography of Wine is incorrect in that there is essentially no "limestone" in this area. There is a tiny outcropping in the extreme West side of San Luis Obispo County, but I believe it lies entirely outside of the Paso Robles appellation. We do have an abundance of "mudstone" which is entirely different than limestone. Limestone is calcium carbonate, and mudstone is calcium silicates. They are completely different in their properties and how they contribute to the terroir.

MB: What about the meteorological differences between East & West?

SO: The West side has 40+ inches of rain per year and the East side has only 12 inches per year. During the summer growing season, the daytime temperature of the West is considerably less than that of the East. Sometimes 10 to 15 degrees cooler.

GE: And these factors make a big difference. If you look at the soils and vegetation on the two sides, you cannot doubt where the fertile soils are. All the truck farming is on the West side. The East side cannot even grow poison oak, yet it is all over the West. The tremendous difference in rainfall between the two areas has a lot to do with this. The large rainfall on the hills to the West allows a lot more natural vegetation to grow and as it decomposes, it creates deep and fertile soils.

The East side does not get enough rain, and our soils are so open that until we found out how to bring up the deep water under this area, growing grapes, vegetables, or any thing else was not possible. Back then, this area was used for dry-farmed barley, and grazing cattle on poverty grass.

JB: So, in a nutshell, the West has double or higher rainfall than the East, cooler daytime highs and nighttime lows, marine and coastal mountain influences, and more stars . . . (laughs)!

MB: Perhaps you could each talk about where you are located and why you chose that specific location?

GE: I did my doctoral work at UC Davis with a major in fermentation science and a minor in viticulture. During my last year at Davis I made three trips to Paso Robles with Drs. Olmo and Alley, and with Jack Foote, who was the local farm advisor here at that time. We dug holes in multiple locations in what is now the Paso appellation, and took soils back to the soil science lab for analysis. It was the results of these reports and meteorological investigations that made me choose the location where I planted my vineyards.

The other major factor in my choice of the East side is that, for the most part, the soils are remarkably infertile. I decided to stay on the infertile soils as the Europeans have learned to do over the centuries when it comes to locating vineyards. Grapes have the ability to reach deep into the soil for their needs. You want the grapes to go deep. Don't grow them on fertile and heavy soils where they stay close to the surface.

SO: I can’t say I really chose one side over the other. We have one vineyard located on Union Road and one located on Creston Road. We also farm and make wine from a vineyard on Adelaida Road and source fruit from all over the West and East side as well as San Miguel, Indian Valley, and Monterey.

I chose the East locations for their unique microclimates, terroirs, and proximity to other premium vineyards producing high quality wines. I like to produce big extracted reds, which are more suited to East side vineyards. I chose the West side vineyard because of the ability to dry farm it, and for its old head-trained Zinfandel, which is more suited to the West side.

JB: Our site is the most northerly, highest in elevation, and furthest West of all the wineries and vineyards in our AVA. We chose the location because it’s beautiful, and for the soils, the southern slope, the amount of water available from our wells, the fact that nobody had ever planted grapes nearby, and because most of the land around me is in large parcels owned by the original Mennonite settlers. Even today there are less than 100 parcels in the 100 square miles surrounding my property.

JB: Our site is the most northerly, highest in elevation, and furthest West of all the wineries and vineyards in our AVA. We chose the location because it’s beautiful, and for the soils, the southern slope, the amount of water available from our wells, the fact that nobody had ever planted grapes nearby, and because most of the land around me is in large parcels owned by the original Mennonite settlers. Even today there are less than 100 parcels in the 100 square miles surrounding my property.MB: Do you think the two subregions have similar ‘Paso Robles’ taste characteristics? If so, what are they?

SO: No, the East side has more big, fruit driven wines that can accumulate higher sugars and more extracted flavors. The West side has more spicy, mineral type