Warren Winiarski's 1973 Cabernet Sauvignon helped put

California on the world wine map.

Stags Leap District ~ Napa Valley (AVA)

Stags Leap's Goût de Terroir: An Interview with Warren Winiarski

"We continue to make wine that expresses the terroir. So, we don’t make over-ripe wines that don’t want to express the site."

by

Alan Goldfarb

September 18, 2006

Alan Goldfarf (AG): I know that when you tasted the wine from Nathan Fay’s vineyard, you were smitten. That’s been well-chronicled. But was that it? Was that enough for you to purchase that parcel?

Warren Winiarski (WW): The tasting was preceded by years of studying the Napa Valley. The Bordelais wines were wines that attracted my very great affection. I was weaned on these wines. It was natural to think that some day I would be able to raise grapes that could be made into wine that could be of a similar profound beauty.

Warren Winiarski (WW): The tasting was preceded by years of studying the Napa Valley. The Bordelais wines were wines that attracted my very great affection. I was weaned on these wines. It was natural to think that some day I would be able to raise grapes that could be made into wine that could be of a similar profound beauty.

In those days, there were no single vineyards. Martha’s Vineyard (one of the first storied vineyards in the modern era that was the source of Heitz Cellars’ signature wine) was not known as being a unique vineyard for its characteristics. Grapes were not believed to have very specific terroir characteristics due to the site. It was the varietal characteristics that counted, not the given place where they were grown. Martha’s wasn’t an exception to that.

Everyone had their special spots, but there was no elaboration for the reasons. Was it soil, climate, or mezzo-climates? All these things weren’t in the vocabulary (in the mid-60s). It was simply named to honor Martha May (the owner, along with her husband).

I was trying to find a spot...without calling it terroir. (In an earlier article, by Alan Goldfarb, Winiarski describes searching for the vineyard's "sweet spot") Where’s the right spot to grow Cabernet? It was a goal of mine. Wineries got grapes from different areas, but the grapes were all blended together. The varietal was the important thing at that time.

In the four years before I bought the winery, I tasted the wines from different areas while I was working at Souverain (which was then located in the Napa Valley.) This gave me an idea what different spots were like. I had this geography in mind and a kind of matrix formed.

All this studying fell together on the day that I tasted Nathan Fay’s wine. It was so profound. It was a culmination. I didn’t articulate that, but this was a feeling.

AG: I bet you can still taste that wine.

WW: Not as vividly, but if I ask for the image, I have that feeling on my palate. It had freshness, acidity. It had a unique combination of softness and structure, strength and suppleness. It had a perfume that was characteristic of rose petals and black cherry. It had persistence. It had fine-grained structural elements. It felt like linen as it moved across your palate. It resonated. It had length and intricacies.

AG: Have you made a wine equal to or one that has surpassed that of Fay’s ‘68?

WW: My ‘78 I thought was like that. I chose the budwood from Nathan’s vineyard and from Martha’s Vineyard. … I chose them for the characteristics in the fruit. They had loose clusters where the sun could more fully irradiate them. It was equal if not better. The ‘77 was almost as good, as well as the ‘85 …

But Nathan’s original vines got out of control. They were not the same quality after a while, but we didn’t know why. They were getting into the big-vine syndrome, becoming more vigorous and the fruit suffered. It became clear what we had to do -- reduce the vines (in ’86).

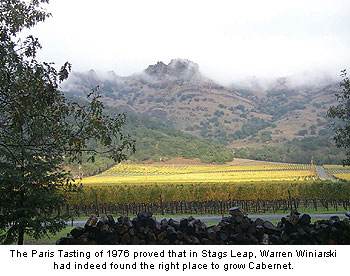

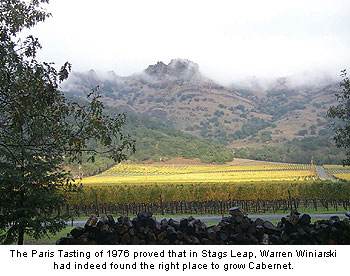

In a recent re-tasting, thirty years after the Paris tasting, the wine was similar to the wines I tasted from Fay. All these characteristics that that ground is capable of, were still present.

AG: Is there a SLD terroir?

AG: Is there a SLD terroir?

WW: There is a characteristic expression but it expresses more or less the site within the appellation. If you grow on the south-facing hills, the characteristics will be different than if you planted on another slope.

What we have here is a combination of two soil characteristics. We have very coarse-particle soils, which lie to the east, and fine-particle soils which lie to the west. The coarse volcanic soil gives the grapes the nature of fire. The fine-particle soil tends to dwell longer in the vegetative stage making the wines softer, smoother and more fleshy.

There’s a middle ground, which is a way to combine these opposite qualities that would otherwise stand out as disunity.

AG: What about your 115 acres in particular?

WW: Part is on alluvial sand, part is volcanic soils, part is the middle mixture, and part of it is where the soils flatten out. These last have characteristics created by the movement of water through the vineyard. It produces smooth, fleshy characteristics.

AG: I’m sure you saw Jim Laube’s column in which he wrote that your wines were underperforming. He said that the Cask 23 is “likely to be earthy and loamy.” But aren’t those descriptors an expression of terroir?

WW: I’m puzzled because we have a waiting list for our wines. (The Cask 23 produces 2,000-3,000 cases a year). Everyone’s opinion is different. There may be something that might not be in alignment but I don’t want to pick a quarrel. He’s entitled to his opinions. It’s still only one man’s palate.

AG: But he uses earthy and loamy as a pejorative.

WW: Loamy means rich as opposed to clay. It’s a positive. Earthy? Does he mean bad earthy, or does he mean good earthy?

I’m still thrilled by these wines. We love to express what’s in those soils. That’s what we’re trying to do. Express the water-generating and the volcanic-fire soils. We are trying to express those soils. We think that adds interest, nuance, and subtlety by putting those together in an organic, unified way.

I’m still thrilled by these wines. We love to express what’s in those soils. That’s what we’re trying to do. Express the water-generating and the volcanic-fire soils. We are trying to express those soils. We think that adds interest, nuance, and subtlety by putting those together in an organic, unified way.

At the recent re-tasting of the Paris tasting (see Dan Berger’s report), which included recently made wines from the same producers, the English panel rated our 2001 Cask No. 1, and overall it was No. 2.

We continue to make wine that expresses the terroir. So, we don’t make over-ripe wines that don’t want to express the site. I believe some critics are bowled over by these over-ripe, overly extracted, powerfully endowed with oak wines that cover up the terroir. The distinctiveness, the subtleties, the nuances are gone.

Our style has remained consistent. The paradigm hasn’t changed.

Warren Winiarski (WW): The tasting was preceded by years of studying the Napa Valley. The Bordelais wines were wines that attracted my very great affection. I was weaned on these wines. It was natural to think that some day I would be able to raise grapes that could be made into wine that could be of a similar profound beauty.

Warren Winiarski (WW): The tasting was preceded by years of studying the Napa Valley. The Bordelais wines were wines that attracted my very great affection. I was weaned on these wines. It was natural to think that some day I would be able to raise grapes that could be made into wine that could be of a similar profound beauty.In those days, there were no single vineyards. Martha’s Vineyard (one of the first storied vineyards in the modern era that was the source of Heitz Cellars’ signature wine) was not known as being a unique vineyard for its characteristics. Grapes were not believed to have very specific terroir characteristics due to the site. It was the varietal characteristics that counted, not the given place where they were grown. Martha’s wasn’t an exception to that.

Everyone had their special spots, but there was no elaboration for the reasons. Was it soil, climate, or mezzo-climates? All these things weren’t in the vocabulary (in the mid-60s). It was simply named to honor Martha May (the owner, along with her husband).

I was trying to find a spot...without calling it terroir. (In an earlier article, by Alan Goldfarb, Winiarski describes searching for the vineyard's "sweet spot") Where’s the right spot to grow Cabernet? It was a goal of mine. Wineries got grapes from different areas, but the grapes were all blended together. The varietal was the important thing at that time.

In the four years before I bought the winery, I tasted the wines from different areas while I was working at Souverain (which was then located in the Napa Valley.) This gave me an idea what different spots were like. I had this geography in mind and a kind of matrix formed.

All this studying fell together on the day that I tasted Nathan Fay’s wine. It was so profound. It was a culmination. I didn’t articulate that, but this was a feeling.

AG: I bet you can still taste that wine.

WW: Not as vividly, but if I ask for the image, I have that feeling on my palate. It had freshness, acidity. It had a unique combination of softness and structure, strength and suppleness. It had a perfume that was characteristic of rose petals and black cherry. It had persistence. It had fine-grained structural elements. It felt like linen as it moved across your palate. It resonated. It had length and intricacies.

AG: Have you made a wine equal to or one that has surpassed that of Fay’s ‘68?

WW: My ‘78 I thought was like that. I chose the budwood from Nathan’s vineyard and from Martha’s Vineyard. … I chose them for the characteristics in the fruit. They had loose clusters where the sun could more fully irradiate them. It was equal if not better. The ‘77 was almost as good, as well as the ‘85 …

But Nathan’s original vines got out of control. They were not the same quality after a while, but we didn’t know why. They were getting into the big-vine syndrome, becoming more vigorous and the fruit suffered. It became clear what we had to do -- reduce the vines (in ’86).

In a recent re-tasting, thirty years after the Paris tasting, the wine was similar to the wines I tasted from Fay. All these characteristics that that ground is capable of, were still present.

AG: Is there a SLD terroir?

AG: Is there a SLD terroir?WW: There is a characteristic expression but it expresses more or less the site within the appellation. If you grow on the south-facing hills, the characteristics will be different than if you planted on another slope.

What we have here is a combination of two soil characteristics. We have very coarse-particle soils, which lie to the east, and fine-particle soils which lie to the west. The coarse volcanic soil gives the grapes the nature of fire. The fine-particle soil tends to dwell longer in the vegetative stage making the wines softer, smoother and more fleshy.

There’s a middle ground, which is a way to combine these opposite qualities that would otherwise stand out as disunity.

AG: What about your 115 acres in particular?

WW: Part is on alluvial sand, part is volcanic soils, part is the middle mixture, and part of it is where the soils flatten out. These last have characteristics created by the movement of water through the vineyard. It produces smooth, fleshy characteristics.

AG: I’m sure you saw Jim Laube’s column in which he wrote that your wines were underperforming. He said that the Cask 23 is “likely to be earthy and loamy.” But aren’t those descriptors an expression of terroir?

WW: I’m puzzled because we have a waiting list for our wines. (The Cask 23 produces 2,000-3,000 cases a year). Everyone’s opinion is different. There may be something that might not be in alignment but I don’t want to pick a quarrel. He’s entitled to his opinions. It’s still only one man’s palate.

AG: But he uses earthy and loamy as a pejorative.

WW: Loamy means rich as opposed to clay. It’s a positive. Earthy? Does he mean bad earthy, or does he mean good earthy?

I’m still thrilled by these wines. We love to express what’s in those soils. That’s what we’re trying to do. Express the water-generating and the volcanic-fire soils. We are trying to express those soils. We think that adds interest, nuance, and subtlety by putting those together in an organic, unified way.

I’m still thrilled by these wines. We love to express what’s in those soils. That’s what we’re trying to do. Express the water-generating and the volcanic-fire soils. We are trying to express those soils. We think that adds interest, nuance, and subtlety by putting those together in an organic, unified way. At the recent re-tasting of the Paris tasting (see Dan Berger’s report), which included recently made wines from the same producers, the English panel rated our 2001 Cask No. 1, and overall it was No. 2.

We continue to make wine that expresses the terroir. So, we don’t make over-ripe wines that don’t want to express the site. I believe some critics are bowled over by these over-ripe, overly extracted, powerfully endowed with oak wines that cover up the terroir. The distinctiveness, the subtleties, the nuances are gone.

Our style has remained consistent. The paradigm hasn’t changed.