In what was the most publicized wine tasting in history, California’s Cabernets again caught the attention of the press, but beyond all the hype, what are the real lessons to be learned from this latest skirmish in the perpetual comparison of California vs. Bordeaux?

California (State Appellation)

The message of Paris ’76 Redux – that California won again – misses the most vital point.

The Judgment of Paris tasting on May 24, 2006, may well have gone to the Californians once again, with the older wines, but the clear message of the event is that terroir character, classic red wine styles, and an understanding of historical perspective remains with Bordeaux.

by

Dan Berger

June 15, 2006

Coordinated at the same time in Napa and London, the twin events clearly captured the fancy of the world’s media like none other in the last few decades. TV cameras and still photographers filled the venues on both sides of the Atlantic. Reporters from major news organizations flooded the rooms, and every major news disseminator carried a story about it.

The fact California again vanquished the French in the head-to-head meeting of the wines originally tasted exactly 30 years earlier became the headline news.

On judging the older wines:

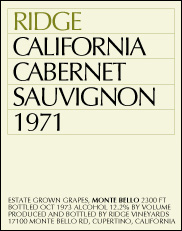

It is one thing to say that the 1971 Ridge Monte Bello Cabernet Sauvignon was the overall winner, and that it won at both venues.

It’s also not insignificant to note the vast majority of observers, who also got a taste of the monumental wines of the past, agreed that most of the wines had held up longer than anyone had a right to expect. Thirty years, after all, is a long time for most wines, and the fact that eight of the 10 tasted in Paris were still lilting examples of their producers’ houses, and that all 10 were actually drinkable, was a real testament to quality wine making.

It’s also not insignificant to note the vast majority of observers, who also got a taste of the monumental wines of the past, agreed that most of the wines had held up longer than anyone had a right to expect. Thirty years, after all, is a long time for most wines, and the fact that eight of the 10 tasted in Paris were still lilting examples of their producers’ houses, and that all 10 were actually drinkable, was a real testament to quality wine making. However, in the rush to judgment on May 24, 2006, a number of major messages about this event were ignored and may be lost forever if we don’t address them. And one of these is the simple fact that the regional character of these wines was never a factor in their evaluation.

The judges knew which wines would be in the evaluation – the same ones that took part in the 1976 evaluation. But since the California wines fooled the French back then, it was assumed one reason was that the evaluators in 1976 had pretty much ignored the terroir aspect of the judging and simply voted on which wines were best. Either that or the California wines were similar in many regards to their Bordeaux competitors.

Certainly, one could have assumed, the evaluators in 2006 would not ignore the terroir elements. They would undoubtedly factor in regional character and make it a part of their determination of what constituted quality.

As one of the California judges, I can say that the thought crossed my mind more than once during the 45-minute evaluation period of the older wines. The major problem was that the parameters of the tasting focused on preference. We were, in effect, asked “Which wines are best?” and not, “Which wines display their terroir and remain great-tasting?”

Unwieldy? Perhaps, but the issue may be more germane than it seems. Of course, since the tasting was blind, no one could seek terroir, wine by wine, since the tasters did not know which wine was a St-Estèphe, which a Pauillac, and which a product of the Napa Valley. However, the tasting was single-blind, and thus evaluators knew which wines would be in the tasting, and could have tried to identify the wines by terroir components.

Then again, with wines so old, is it quite likely that terroir components would still be visible? As a professional wine evaluator for 30 years, I can say that any wine that reaches that exalted age ought to be considered a miracle if it retains sufficient fruit to be called enjoyable. Any terroir components left in the wine would be a bonus.

On judging the younger wines:

So dwelling any further on the older wines seems at this point to be rather pointless, and we should move on to the younger wines of Paris ’76 Redux. There were groups of six Bordeaux and six California wines that were judged side-by-side, but not against each other. (The French were opposed to yet another tête-à-tête comparison judging in which they could well be shown up yet again.)

Curiously enough, for the vast majority of the tasters at both the Napa and London sessions, had the comparison been staged as a real competition between the wines, I believe the French would unquestionably have won. I say this after casual conversations with most of the judges as well as the observers who tasted the wines.

This is due in part to the fact that most of the judges were professionals who seek a more classical construction than was evident in the California wines.

From my own notes, I can say that my first two French wines in terms of overall quality, 2000 Château Montrose and 2000 Château Latour, both showed distinctive terroir-based elements that were most intriguing and which gave the wines a je ne sais quoi “Bordeauxishness” that seemed anticipatory to what the wines will be in a few years.

By contrast, the California Cabernet Sauvignons we tried, including some reputedly monumental wines, were uniformly soft and uninteresting from a historical point of view. By that I mean that they were radically different from the wines that had just beaten the French a second time, 30 years later. Those earlier wines were made in a more refined, classical style, emulating what the Bordelais themselves were forced into by their soils and their continental climate – conditions that set the paradigm for classic Cabernet Sauvignon based wines.

The newer California wines had evolved in terms of style. Far riper and more “fruit” forward (and I use the term with a jaundiced eye, since the fruit referred to is almost entirely raisin or prune like) style of wine without the underpinnings to age more than a few years.

California wine makers tell me all the time that this is what the consumer wants. The almost complete lack of any terroir based elements in these wines is of absolutely no concern to these point guided wine makers, for whom a score in the high 90s by one of the power reviewers is the end all of life.

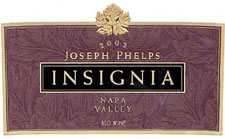

Indeed, the Wine Spectator’s selection for ‘Wine of the Year’ is a “monumental” red wine from Joseph Phelps; the iconic Insignia from the 2002 vintage.

My tasting notes on the wine, however, differ radically from that point of perception. Tasting the wine double-blind, my tasting notes reflect a lower ranking:

My tasting notes on the wine, however, differ radically from that point of perception. Tasting the wine double-blind, my tasting notes reflect a lower ranking:

- “Faintly over-ripe, fat, tannic, soft and juicy. Made from excellent fruit that was partially and inappropriately allow to raisin. The wine has a higher alcohol than appropriate for a classic red wine. Age it three to four years max.”

Note, in my tasting notes, there was a complete lack of any reference to terroir components. That’s because there were none. In fact, Insignia is a blend from various areas of the Napa Valley and has never exhibited a terroi