Riesling and Cabernet Sauvignon...

...unlikely neighbors on Spring Mountain.

Spring Mountain District ~ Napa Valley (AVA)

Spring Mountain winegrower and vintner, Charles Smith

Three and a half decades on the mountain has given Charles Smith a deep understanding of what it takes to grow and produce great wines on these steep slopes.

by

Alan Goldfarb

August 4, 2006

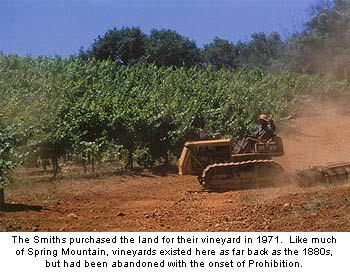

Alan Goldfarb (AG): Why did you and your brother decide to purchase land on Spring Mountain?

Charles Smith (CS): I knew Stony Hill’s whites, and Draper was producing top caliber Cabernet. There was a definite feeling that moving into the hills (to plant grapes) was a good thing. Worldwide it’s not too difficult to define that (hillsides) are the place for making top level wines. It seemed like a fairly easy call.

Charles Smith (CS): I knew Stony Hill’s whites, and Draper was producing top caliber Cabernet. There was a definite feeling that moving into the hills (to plant grapes) was a good thing. Worldwide it’s not too difficult to define that (hillsides) are the place for making top level wines. It seemed like a fairly easy call.

It also turned out that there was water on the property. Contrary to what amateurs think, little grapevines really like water. When they are just a year old, you can’t have struggling little plants. It’s Basic Viticulture 101. I think the books give the wrong idea about that (stressing the vines by providing as little water possible).

AG: How much of an influence did McCrea and Draper have?

CS: Stony Hill is a real model for us. Stony Hill was one of the pioneering wineries in the valley. Their Chardonnay and Riesling were a huge influence; and the fact that there was so much good Cab coming off of Draper’s property. The connection between Draper and Beaulieu was terrific.

AG: How is Spring Mountain different from other areas of the Napa Valley?

CS: Spring Mountain has a great deal in common with Diamond Mountain and Mount Veeder; more so than with the valley floor directly below. We hear and we read about micro-climates, and I’m not entirely clear where the separation is between climate and micro-climate. (But) up in the hills it’s not just a different micro- climate, it’s a different climate. It snows, it’s a lot cooler, and there’s more rain. We have inversion layers where at night it can be warm. We’ve probably got more sunshine, too.

I think hillside wines have a lot of structure and a lot of intensity of fruit. Wines up here can be characterized by a kind of compactness. Parenthetically, a good vintage (up here) is a good vintage in all varieties for us. … You see flavors that are penetrating.

AG: What possessed you to plant Riesling – and continue to plant the variety – when all your neighbors, with the exception of Stony Hill, apparently think that only red grapes do best on the mountain?

CS: Stony Hill, of course, was and is something of an influence. It was our judgment then as it is now, that those four varieties (Cabernet, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and Riesling) are the most interesting and important varieties. We had invested to make quality wines, just like anyone else.

Riesling wasn’t risky in those days. It was widely planted and it was good quality. Pinot Noir was more risky. It was planted for the love of the grape. Leon Adams and Nathan Croman wrote about it. And there was very little planted in the hills. It seemed like an interesting thing to do.

We made it in the old-fashioned, rich, round Burgundy style. It didn’t work for us. It’s a little too warm up here. We were on the same learning curve that everyone else had to go through. Our 1980 (Pinot) was a world-beater but we couldn’t do it again.

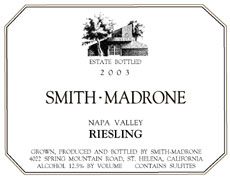

The very first wine we made – Riesling (in ’77) – won this huge tasting in Paris. We were on the front page of the International Tribune. It wasn’t difficult to plant, and it didn’t seem viticulturally or oenologically difficult in any way. The tricky part was keeping it (growing).

People who move up into the hills, generally are people who tend to go their own way. With us (Charles and Stuart), we had a running debate for a long time in the mid-80s about whether or not to pull out the Riesling and plant Chardonnay. Chard was so huge and Riesling was so clearly in decline. So, I thought we should seriously consider abandoning Riesling.

Chard was so huge and Riesling was so clearly in decline. So, I thought we should seriously consider abandoning Riesling.

Fortunately I lost. Stuart kept saying, “We won this tasting, it’s easy to sell, people love it.” He said we should keep on making it for collateral reasons. If everyone stopped making it, we (knew) we could do it very, very well. It would make us a little more visible.

We didn’t understand at the time how beautifully these wines age. There would have been no way to find this out if we had abandoned it. It’s a little miracle when you get to taste the old Rieslings. We didn’t see it coming. We didn’t understand we’d want to drink these wines in 12, 15 years.

AG: Do you foresee a time when Riesling will make a comeback in the valley?

CS: It appears to be making a small comeback (now). But what the extent is isn’t clear to me. There does seem to be an increased interest, especially with the under-40 group.

Of all the wines we make, no wine represents terroir evidence as does Riesling. We’ve never fundamentally changed the way we make it. It is directly aligned from vineyard to bottle. We’re not manipulating or fooling with the wine. We don’t have extended skin contact. You crush it, you ferment it, you bottle it. When you taste a vertical of our Riesling, you are tasting the same wines. The differences are in the vintages.

Of all the wines we make, no wine represents terroir evidence as does Riesling. We’ve never fundamentally changed the way we make it. It is directly aligned from vineyard to bottle. We’re not manipulating or fooling with the wine. We don’t have extended skin contact. You crush it, you ferment it, you bottle it. When you taste a vertical of our Riesling, you are tasting the same wines. The differences are in the vintages.

AG: Do you think then that Spring Mountain is the best place in the valley for Riesling?

CS: I wouldn’t have any idea. I don’t know. It’s entirely likely. If I say yes, I’m putting down Trefethen (which makes the varietal) and I don’t want to do that. … There’s so little Riesling around to comment on that. (But) it’s clear that off the valley floor is very good for Riesling.

AG: Why on Spring Mountain?

CS: It’s cooler and the vines have to struggle. We’re also very pleased with the quality of our Cabernet, and it’s quite reasonable to grow Riesling and Cab side-by-side. It’s quite remarkable, and I think we’re showing that it’s entirely possible. It’s unusual, odd and it’s interesting.

AG: What about your Cabernets? You always seem to have lower-than-14 percent alcohol Cabs. How come you pick less ripe and produce lower alcohol percentage wines, when all your colleagues are pushing those numbers in the opposite direction?

(see Alan Goldfarb's review of the

Charles Smith (CS): I knew Stony Hill’s whites, and Draper was producing top caliber Cabernet. There was a definite feeling that moving into the hills (to plant grapes) was a good thing. Worldwide it’s not too difficult to define that (hillsides) are the place for making top level wines. It seemed like a fairly easy call.

Charles Smith (CS): I knew Stony Hill’s whites, and Draper was producing top caliber Cabernet. There was a definite feeling that moving into the hills (to plant grapes) was a good thing. Worldwide it’s not too difficult to define that (hillsides) are the place for making top level wines. It seemed like a fairly easy call. It also turned out that there was water on the property. Contrary to what amateurs think, little grapevines really like water. When they are just a year old, you can’t have struggling little plants. It’s Basic Viticulture 101. I think the books give the wrong idea about that (stressing the vines by providing as little water possible).

AG: How much of an influence did McCrea and Draper have?

CS: Stony Hill is a real model for us. Stony Hill was one of the pioneering wineries in the valley. Their Chardonnay and Riesling were a huge influence; and the fact that there was so much good Cab coming off of Draper’s property. The connection between Draper and Beaulieu was terrific.

AG: How is Spring Mountain different from other areas of the Napa Valley?

CS: Spring Mountain has a great deal in common with Diamond Mountain and Mount Veeder; more so than with the valley floor directly below. We hear and we read about micro-climates, and I’m not entirely clear where the separation is between climate and micro-climate. (But) up in the hills it’s not just a different micro- climate, it’s a different climate. It snows, it’s a lot cooler, and there’s more rain. We have inversion layers where at night it can be warm. We’ve probably got more sunshine, too.

I think hillside wines have a lot of structure and a lot of intensity of fruit. Wines up here can be characterized by a kind of compactness. Parenthetically, a good vintage (up here) is a good vintage in all varieties for us. … You see flavors that are penetrating.

AG: What possessed you to plant Riesling – and continue to plant the variety – when all your neighbors, with the exception of Stony Hill, apparently think that only red grapes do best on the mountain?

CS: Stony Hill, of course, was and is something of an influence. It was our judgment then as it is now, that those four varieties (Cabernet, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and Riesling) are the most interesting and important varieties. We had invested to make quality wines, just like anyone else.

Riesling wasn’t risky in those days. It was widely planted and it was good quality. Pinot Noir was more risky. It was planted for the love of the grape. Leon Adams and Nathan Croman wrote about it. And there was very little planted in the hills. It seemed like an interesting thing to do.

We made it in the old-fashioned, rich, round Burgundy style. It didn’t work for us. It’s a little too warm up here. We were on the same learning curve that everyone else had to go through. Our 1980 (Pinot) was a world-beater but we couldn’t do it again.

The very first wine we made – Riesling (in ’77) – won this huge tasting in Paris. We were on the front page of the International Tribune. It wasn’t difficult to plant, and it didn’t seem viticulturally or oenologically difficult in any way. The tricky part was keeping it (growing).

People who move up into the hills, generally are people who tend to go their own way. With us (Charles and Stuart), we had a running debate for a long time in the mid-80s about whether or not to pull out the Riesling and plant Chardonnay.

Chard was so huge and Riesling was so clearly in decline. So, I thought we should seriously consider abandoning Riesling.

Chard was so huge and Riesling was so clearly in decline. So, I thought we should seriously consider abandoning Riesling.

Fortunately I lost. Stuart kept saying, “We won this tasting, it’s easy to sell, people love it.” He said we should keep on making it for collateral reasons. If everyone stopped making it, we (knew) we could do it very, very well. It would make us a little more visible.

We didn’t understand at the time how beautifully these wines age. There would have been no way to find this out if we had abandoned it. It’s a little miracle when you get to taste the old Rieslings. We didn’t see it coming. We didn’t understand we’d want to drink these wines in 12, 15 years.

AG: Do you foresee a time when Riesling will make a comeback in the valley?

CS: It appears to be making a small comeback (now). But what the extent is isn’t clear to me. There does seem to be an increased interest, especially with the under-40 group.

Of all the wines we make, no wine represents terroir evidence as does Riesling. We’ve never fundamentally changed the way we make it. It is directly aligned from vineyard to bottle. We’re not manipulating or fooling with the wine. We don’t have extended skin contact. You crush it, you ferment it, you bottle it. When you taste a vertical of our Riesling, you are tasting the same wines. The differences are in the vintages.

Of all the wines we make, no wine represents terroir evidence as does Riesling. We’ve never fundamentally changed the way we make it. It is directly aligned from vineyard to bottle. We’re not manipulating or fooling with the wine. We don’t have extended skin contact. You crush it, you ferment it, you bottle it. When you taste a vertical of our Riesling, you are tasting the same wines. The differences are in the vintages. AG: Do you think then that Spring Mountain is the best place in the valley for Riesling?

CS: I wouldn’t have any idea. I don’t know. It’s entirely likely. If I say yes, I’m putting down Trefethen (which makes the varietal) and I don’t want to do that. … There’s so little Riesling around to comment on that. (But) it’s clear that off the valley floor is very good for Riesling.

AG: Why on Spring Mountain?

CS: It’s cooler and the vines have to struggle. We’re also very pleased with the quality of our Cabernet, and it’s quite reasonable to grow Riesling and Cab side-by-side. It’s quite remarkable, and I think we’re showing that it’s entirely possible. It’s unusual, odd and it’s interesting.

AG: What about your Cabernets? You always seem to have lower-than-14 percent alcohol Cabs. How come you pick less ripe and produce lower alcohol percentage wines, when all your colleagues are pushing those numbers in the opposite direction?

(see Alan Goldfarb's review of the

Print this article | Email this article | More about Spring Mountain District ~ Napa Valley | More from Alan Goldfarb