Oregon's wine culture is as diverse as its terroir.

Oregon Wines: Exploring Terroir of the Land and the Mind

"For wine lovers, Oregon’s contrasting character is manifest in our wines and the people who grow and make them. In Oregon, there is a terroir of the mind as much as there is a terroir of the land."

by

Cole Danehower

November 1, 2006

Oregon Vintage 2006: The Challenge of Change

Forty years ago this spring, David Lett went against the best advice of his UC Davis professors and put Oregon’s first Pinot Noir plants into the hilly red earth outside Dundee, just southwest of Portland. Vintage 2006 marks the 40th anniversary of the birth of Oregon’s Pinot Noir industry. And yet the occasion passed with relatively little notice as winemakers went about harvesting their grapes.

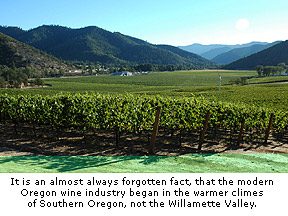

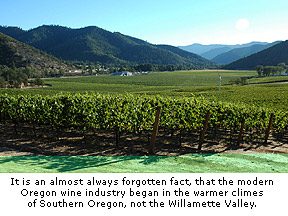

A few years before Lett arrived, another offbeat pioneer had planted Riesling

in what he considered to be an optimal site outside of Roseburg, in the warmer climate of Southern Oregon. Richard Sommer was the founder of Oregon’s fine wine industry, yet today his name is little more than an historical footnote, and Riesling has been relegated to an eccentric, niche status.

A few years before Lett arrived, another offbeat pioneer had planted Riesling

in what he considered to be an optimal site outside of Roseburg, in the warmer climate of Southern Oregon. Richard Sommer was the founder of Oregon’s fine wine industry, yet today his name is little more than an historical footnote, and Riesling has been relegated to an eccentric, niche status.

Perhaps the breakneck growth of today’s Oregon wine industry has simply overwhelmed any collective sense of history here, or maybe the opportunities are simply so great that people would rather look forward than backward. Yet it is the history of Oregon’s wine industry that provides the frame for a canvas of new challenges facing the state’s wine growers and producers. With the 2006 harvest, Oregon’s wine industry finds itself 40 years old, and in a condition of transition that is both painful and exhilarating.

On the one hand, Oregon’s vintners are experiencing more success and respect than ever before. After a long history of struggling for market success, economic good times, great quality wines, and expanding demand means that Oregon’s wineries are selling out their wines with unprecedented speed -- and with easy support for premium prices. Good vintages and more experienced growing and winemaking is resulting in more reliable wine quality, which in turn is bringing higher critical wine scores and unprecedented market attention.

These are good times for Oregon.

On the other hand, the industry is struggling to deal with the less savory effects of its own success. An explosive growth in new wineries and premium labels has introduced a new level of variability that could risk Oregon’s reputation for quality. Not every new label deserves a $45 price tag. An influx of new money and development visions are creating polarizing views of how to best use the state’s wine country resources. Do you embrace resort development or not? And many wonder whether the Oregon wine industry’s distinctive culture of cooperation, craft, and community will be able to survive in the face of economic growth and success.

These are challenging times for Oregon.

And you can add to this potentially volatile mix, the natural changing of generations as the founding pioneers of Oregon’s wine community begin to retire, sell their businesses, or transition ownership to their children. Change may be inevitable, but it is rarely easy.

Defining Oregon Pinot

Oregon is best known for its Pinot Noirs. One important point of change for the state’s industry is in the ongoing evolution of a distinctly Willamette Valley-style of Pinot Noir. Is there an Oregon-specific Pinot Noir style?

Oregon is best known for its Pinot Noirs. One important point of change for the state’s industry is in the ongoing evolution of a distinctly Willamette Valley-style of Pinot Noir. Is there an Oregon-specific Pinot Noir style?

I attended a recent trade tasting, where a flight of 2002 Willamette Valley Pinot Noirs was presented to a knowledgeable group of distributors. The color of the wines was fairly uniform, but for one obvious exception. One wine was distinctly wan-colored, slightly brickish, and lacked hue intensity. “Must be an old vintage,” ventured one attendee, as they pondered the anomalous wine.

The paler Pinot was not an older vintage; it was the current product of The Eyrie Vineyards, David Lett’s founding Pinot Noir winery. It stood out because Lett makes Oregon Pinot Noir in the same style in which he has always made it: fully organic winegrowing, hand-picking at maximum flavor ripeness, native fermentation, gravity-fed wine movement, minimal oak. Eyrie Pinot Noirs are almost always lighter colored than the average for the area.

The Eyrie Pinot stood out because the predominant style of Oregon Pinot noir has shifted over the years away from Lett’s style. Here is how he describes it:

“I’ve been frustrated for the last decade, by the wine press which has promoted, and in effect created, an international-style Pinot Noir whose varietal characteristics seem to be high alcohol, lots of oak, deep color, and plummy-jammy flavors. This to my mind means artificially manipulated wines made from over-ripe grapes that could come from anywhere!”

In more recent years -- partly due to warm vintages that produced high sugars and heavy wines, and partly due to a winemaking style that emphasizes highly extracted Pinots that seem to win high scores -- the more typical Willamette Valley Pinot Noir has had deep coloration, alcohol levels at 14% or more, heavy oak influence, and weighty, substantial tannins and texture.

Which of these styles is the “proper” Oregon Pinot Noir? Indeed, is there even a “typical” Oregon Pinot Noir?

In Lett’s opinion, there is a proper Oregon style . . . and it is not today’s trend (though he has hope . . .):

“The pinnacle that a wine maker can reach is to preserve the varietal characteristic of a grape grown in a proper climate (which is the only place you can get that varietal characteristic) and translate that into wine. I’m glad to see the glimmering of a new trend for Pinot Noir, away from the score-driven excesses of the 90s, and more towards what Oregon can do better than almost anywhere else on earth: produce Pinot Noir that tastes like Pinot Noir. That’s why I came to the Willamette Valley!”

Many new Oregon Pinot producers aren’t paying a great deal of attention to “style” and are making wines in a manner that they believe will sell well. Look down a lineup of current releases of Willamette Valley Pinot and you’ll see high alcohol, deep colors, jammy flavors and big wood. You’ll also see big scores and hefty prices.

Yet, talk to the winemakers and you detect a desire to identify an indigenous character that is more a reflection of the Willamette Valley’s broad terroir, than a winemaker’s stylistic stamp.

“I think the hallmarks of Oregon Pinot are fruit and intensity,” says Laurent Montalieu, who makes wine for a variety of labels, as well as his own Soléna brand in Carlton. “For me, Oregon Pinots are characterized by great intensity -- particularly red fruits -- and though there are differences among the AVAs, they all have lots of brightness and liveliness in the mouth, and good fresh aromatics.”

Alex Sokol Blosser, vice president at Sokol Blosser winery, agrees. “I think Oregon’s Pinots are driven primarily by forward fruit and also by structure, par

Forty years ago this spring, David Lett went against the best advice of his UC Davis professors and put Oregon’s first Pinot Noir plants into the hilly red earth outside Dundee, just southwest of Portland. Vintage 2006 marks the 40th anniversary of the birth of Oregon’s Pinot Noir industry. And yet the occasion passed with relatively little notice as winemakers went about harvesting their grapes.

A few years before Lett arrived, another offbeat pioneer had planted Riesling

in what he considered to be an optimal site outside of Roseburg, in the warmer climate of Southern Oregon. Richard Sommer was the founder of Oregon’s fine wine industry, yet today his name is little more than an historical footnote, and Riesling has been relegated to an eccentric, niche status.

A few years before Lett arrived, another offbeat pioneer had planted Riesling

in what he considered to be an optimal site outside of Roseburg, in the warmer climate of Southern Oregon. Richard Sommer was the founder of Oregon’s fine wine industry, yet today his name is little more than an historical footnote, and Riesling has been relegated to an eccentric, niche status.Perhaps the breakneck growth of today’s Oregon wine industry has simply overwhelmed any collective sense of history here, or maybe the opportunities are simply so great that people would rather look forward than backward. Yet it is the history of Oregon’s wine industry that provides the frame for a canvas of new challenges facing the state’s wine growers and producers. With the 2006 harvest, Oregon’s wine industry finds itself 40 years old, and in a condition of transition that is both painful and exhilarating.

On the one hand, Oregon’s vintners are experiencing more success and respect than ever before. After a long history of struggling for market success, economic good times, great quality wines, and expanding demand means that Oregon’s wineries are selling out their wines with unprecedented speed -- and with easy support for premium prices. Good vintages and more experienced growing and winemaking is resulting in more reliable wine quality, which in turn is bringing higher critical wine scores and unprecedented market attention.

These are good times for Oregon.

On the other hand, the industry is struggling to deal with the less savory effects of its own success. An explosive growth in new wineries and premium labels has introduced a new level of variability that could risk Oregon’s reputation for quality. Not every new label deserves a $45 price tag. An influx of new money and development visions are creating polarizing views of how to best use the state’s wine country resources. Do you embrace resort development or not? And many wonder whether the Oregon wine industry’s distinctive culture of cooperation, craft, and community will be able to survive in the face of economic growth and success.

These are challenging times for Oregon.

And you can add to this potentially volatile mix, the natural changing of generations as the founding pioneers of Oregon’s wine community begin to retire, sell their businesses, or transition ownership to their children. Change may be inevitable, but it is rarely easy.

Defining Oregon Pinot

Oregon is best known for its Pinot Noirs. One important point of change for the state’s industry is in the ongoing evolution of a distinctly Willamette Valley-style of Pinot Noir. Is there an Oregon-specific Pinot Noir style?

Oregon is best known for its Pinot Noirs. One important point of change for the state’s industry is in the ongoing evolution of a distinctly Willamette Valley-style of Pinot Noir. Is there an Oregon-specific Pinot Noir style?I attended a recent trade tasting, where a flight of 2002 Willamette Valley Pinot Noirs was presented to a knowledgeable group of distributors. The color of the wines was fairly uniform, but for one obvious exception. One wine was distinctly wan-colored, slightly brickish, and lacked hue intensity. “Must be an old vintage,” ventured one attendee, as they pondered the anomalous wine.

The paler Pinot was not an older vintage; it was the current product of The Eyrie Vineyards, David Lett’s founding Pinot Noir winery. It stood out because Lett makes Oregon Pinot Noir in the same style in which he has always made it: fully organic winegrowing, hand-picking at maximum flavor ripeness, native fermentation, gravity-fed wine movement, minimal oak. Eyrie Pinot Noirs are almost always lighter colored than the average for the area.

The Eyrie Pinot stood out because the predominant style of Oregon Pinot noir has shifted over the years away from Lett’s style. Here is how he describes it:

“I’ve been frustrated for the last decade, by the wine press which has promoted, and in effect created, an international-style Pinot Noir whose varietal characteristics seem to be high alcohol, lots of oak, deep color, and plummy-jammy flavors. This to my mind means artificially manipulated wines made from over-ripe grapes that could come from anywhere!”

In more recent years -- partly due to warm vintages that produced high sugars and heavy wines, and partly due to a winemaking style that emphasizes highly extracted Pinots that seem to win high scores -- the more typical Willamette Valley Pinot Noir has had deep coloration, alcohol levels at 14% or more, heavy oak influence, and weighty, substantial tannins and texture.

Which of these styles is the “proper” Oregon Pinot Noir? Indeed, is there even a “typical” Oregon Pinot Noir?

In Lett’s opinion, there is a proper Oregon style . . . and it is not today’s trend (though he has hope . . .):

“The pinnacle that a wine maker can reach is to preserve the varietal characteristic of a grape grown in a proper climate (which is the only place you can get that varietal characteristic) and translate that into wine. I’m glad to see the glimmering of a new trend for Pinot Noir, away from the score-driven excesses of the 90s, and more towards what Oregon can do better than almost anywhere else on earth: produce Pinot Noir that tastes like Pinot Noir. That’s why I came to the Willamette Valley!”

Many new Oregon Pinot producers aren’t paying a great deal of attention to “style” and are making wines in a manner that they believe will sell well. Look down a lineup of current releases of Willamette Valley Pinot and you’ll see high alcohol, deep colors, jammy flavors and big wood. You’ll also see big scores and hefty prices.

Yet, talk to the winemakers and you detect a desire to identify an indigenous character that is more a reflection of the Willamette Valley’s broad terroir, than a winemaker’s stylistic stamp.

“I think the hallmarks of Oregon Pinot are fruit and intensity,” says Laurent Montalieu, who makes wine for a variety of labels, as well as his own Soléna brand in Carlton. “For me, Oregon Pinots are characterized by great intensity -- particularly red fruits -- and though there are differences among the AVAs, they all have lots of brightness and liveliness in the mouth, and good fresh aromatics.”

Alex Sokol Blosser, vice president at Sokol Blosser winery, agrees. “I think Oregon’s Pinots are driven primarily by forward fruit and also by structure, par