You should be able to discern the vineyard in your glass but you can't if high alcohol masks the appellation. Thus, appellation transparency.

Regional Transparency - When Marketing Trumps Winemaking

In the second of his two part series, Editor-at-Large Dan Berger shows how he thinks wineries are producing wines calculated to garner select critical praise and resulting sales, all at the sacrifice of appellation distinctiveness. While Berger cites the Rutherford AVA as a vehicle for his argument, he is merely using it as an illustrative example of a practice that sadly is widespread.

by

Dan Berger

September 25, 2007

Some might argue that the loss of varietal and regional characteristics has occurred as a result of factors totally out of the hands of man’s control (such as “global warming” or “super yeasts” or some other nonsense). It is clear to me that what has happened in Napa and other areas in California is a conscious effort on the part of wine makers to deal with a number of difficult factors. Winemakers are trying to make wines that both justify a high price and appeal to some of the more recognizable wine critics who prefer wines that are powerful and flavored rather atypically to what was previously rated as great. (Such as the wines that vanquished the French in 1976.)

This was not the case in the 1970s and 1980s when wines were made from grapevines grown far differently from the way they are today, and when wines weren’t being compared with some ethereal paradigm that, frankly, does not represent very good wine. Back then, the top Napa Valley Cabernets were seen as collectibles mainly because they were balanced, improved in the bottle, and delivered a charming level of fruit and complexity over a decade or two. Or more.

Today’s more heavy-handed styles of wines don’t appear to be aging as long or delivering as much complexity. Indeed, the lack of regional definition has left many of the wines with a hollow mid-palate that is filled mainly with alcohol and oak. In fact, the instant hedonism that some ascribe to some of these wines is more likely a result of aging in expensive French oak barrels. Caramelized flavors are, after all, appealing in a circus atmosphere.

Goodbye Phylloxera, Hello Big Vines

The key factors in how we got to this point - where alcohol is up, regional character is out, and flavor definition is compromised - probably began two decades ago when we began to hear reports of phylloxera hitting Napa Valley vineyards (and elsewhere). A lot of the vines were planted on the AxR1 rootstock, which was well known to be susceptible to that particular root louse. Soon after it was developed, AxR1 was prized for its ability to produce significantly larger crops than did other rootstocks.

The transition from AxR1 to less phylloxera susceptible rootstocks combined with virus free budwood has thrown off the balance between vine vigor and sugar development in many California vineyards.

When phylloxera hit, most wineries began to tear out the infected vines and many in the North Coast decided to use devigorating rootstocks, a complete reversal from the vigorous AxR1 that had existed before.

Moreover, the top wood (called scion wood) varietal material they chose to graft on top was virus free. Prior to phylloxera, much of the vine material in the North Coast was infected with viruses. Leaf roll virus in particular was actually beneficial, say many growers, because it helped to retard sugar development and allowed the grapes to ripen in terms of flavor maturity longer into the season without high sugars threatening the ultimate balance of the wine with excessive alcohols. It was the root system’s vigor that kept the vine in balance.

This was the situation for California’s North Coast for some 20 to 30 years or more, and growers got to know how to deal with their vines under this regime: vigor below ground, retarded

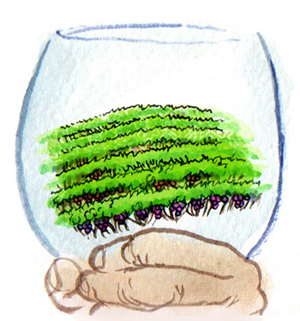

Vertical Shoot Positioning controls vine canopies exposing

grape clusters to more direct sunlight.

Then came another innovation: a new trellising system called vertical shoot positioning (VSP). Older trellising systems had larger canopies of leaves, which also slowed sugar accumulation by not allowing as much sunlight onto the grapes. The VSP method, which was chosen partially because it was easy to manage, allows the vine’s fruit-bearing arms to be lifted well above the level at which they once grew, making the leaf canopy thinner and accordingly, exposing the fruit more directly to sunlight. Among other things, this insured what some wine makers said was complete ripeness of the fruit.

Make Mine Ultra-Ripe Please

Many wine makers saw this as a crucial factor in pleasing some wine critics who liked the more ultra-ripe flavors and seemed to dislike the more varietal/regional elements found in Cabernet Sauvignon from more shaded vines. Such wines are slightly greener and more herbal. The key ingredient in Cabernet Sauvignon as well as Merlot and other varieties was methoxypyrazine (or simply pyrazine for short). It was soon the target of near-universal derision and scorn.The California Sprawl trellising systems of the past seemed to encourage the grapes to retain traces of this naturally occurring component, which is related to both varietal as well as regional character. It was regularly seen in Bordeaux of vintages prior to 1982. By switching to VSP trellises, California growers made life a bit easier in terms of canopy management, and they were able to get more direct sunlight onto the grapes, which generally had the effect of diminishing pyrazine character.

As a result, three major changes had occurred in the vineyards (new roots, new virus-free scion wood, new trellising). So those growers and wine makers who had learned what was happening in their vineyards for decades under varying weather conditions now had to discard what they knew and had to re-learn how to deal with their vines. Moreover, the (new) demand to make a wine with no pyrazine elements encouraged growers to harvest later and later.

Alas, ultra-late har

Read

Read  READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,