Steve Shepard recognizes the Yadkin Valley is still defining itself. But you have to draw a line

in the sand somewhere.

Discovering North Carolina's Yadkin Valley with Steve Shepard of RayLen Vineyards

"I believe the potential for this region is huge. We can produce world class wines. We can compete with wines from around the world in terms of quality and price."

by

Barbara Ensrud

September 12, 2006

Barbara Ensrud (BE): What brought you to North Carolina as a winemaker, and specifically to Yadkin Valley?

Steve Shepard (SS): After finishing college in 1984, I had completed an apprentice program in Pennsylvania and moved on to another winery in the state. In 1989, after 5 years at Shuster Cellars, I had the opportunity to move to North Carolina to help start Westbend Vineyards. After seeing what Virginia was doing, I felt that the climate in North Carolina was more appropriate to growing vinifera Westbend was actually pioneering the wine industry in the entire state, and they were making great strides in the vineyards with Vinifera. I worked over 10 years at Westbend, before moving on to RayLen in 2000. At Westbend we were in the middle of what would become the Yadkin Valley AVA.

BE: The Yadkin Valley is North Carolina's first AVA. As one of the earliest winemakers in this appellation, what characteristics have you seen evolve that are particular to this region?

BE: The Yadkin Valley is North Carolina's first AVA. As one of the earliest winemakers in this appellation, what characteristics have you seen evolve that are particular to this region?

SS: The quality and characteristics of the wine have evolved in the Yadkin Valley over the past several years largely because of the increase in the number of wineries. This area has not shown its best yet, but it is only a matter of time.

One of the exciting developments is that many new growers are experimenting with varieties other than the traditional Chardonnay, Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon. Growers are planting Italian and Spanish varieties as well. In the next 10 years, we’ll gradually learn what varieties are best suited for particular sites.

BE: What were the main criteria used to delineate Yadkin Valley as an appellation?

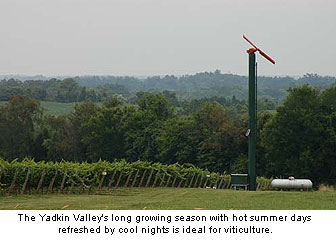

SS: The Yadkin Valley is an area that follows the contour of the Yadkin River. The elevation is a significant aspect of the region, ranging from about 1300 feet down to around 700 feet. This seems to provide the proper climatic conditions for wine grape growing in our region. The winters are not extreme but yet we observe temperatures in the teens overnight which help minimize fungus spores, insect populations and possibly Pierce's disease. Springtime normally brings ample rainfall. Our summers are usually hot and dry which drives sugar to optimum levels. The cool nights traditionally don’t start until September so later varieties (red varieties) benefit from this aspect. All in all, the growing season is long so that the vines have plenty of time to harden off even after harvest. This contributes to the health of vine for a month and a half or two before frost so that vines can slowly acclimate to cooler temperatures after harvest.

The soils vary from higher to lower elevations. The higher elevations tend to have higher percentages of organic matter contained in heavier clay. Clay soils have a greater moisture holding capacity, so during a long dry summer, vines will thrive. Some of the better vineyard sites are on slopes, so if heavy rains occur in the late summer, most of the water runs off. Some vineyards have tried to plant close to the river where the soils are sandy with silt and very well drained, but spring frost can be the worst enemy on these sites.

BE: Has a greater understanding of the terroir of Yadkin led to changes in viticultural practices since you came here? I’m thinking of the trellising systems, for instance.

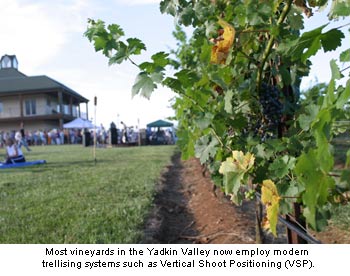

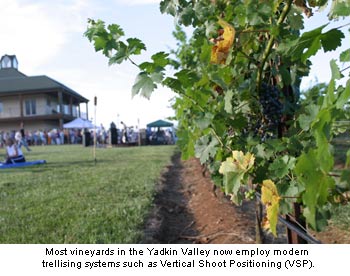

SS: Vertical shoot positioning or VSP has mostly been the system of choice. The open lyre system is showing up at various locations and it is proving to be the better choice on vigorous sites. The main change in viticultural practice is that trellis systems, whatever they may be, are more professionally installed. Many vineyards in the past used old locust trees or cedar trees for post. Minimal fixed wires (1-3 total) were used whereas now several catch wires (2-3 sets) that are movable during the growing season along with fruiting wires are being used.

SS: Vertical shoot positioning or VSP has mostly been the system of choice. The open lyre system is showing up at various locations and it is proving to be the better choice on vigorous sites. The main change in viticultural practice is that trellis systems, whatever they may be, are more professionally installed. Many vineyards in the past used old locust trees or cedar trees for post. Minimal fixed wires (1-3 total) were used whereas now several catch wires (2-3 sets) that are movable during the growing season along with fruiting wires are being used.

Another development is that many new growers are installing irrigation in the first year. Hedging is becoming normal practice as well.

BE: Do you believe the appellation's designated boundaries are valid and meaningful? Do they need to be revised?

SS: The designated boundaries are based on topographic and geological research. When it comes to drawing a line in the sand you have to choose a spot. The original proposed boundaries have been revised to extend further south along the river basin. The boundaries must be valid and meaningful or they would not be there. I feel that there are other potential appellations in our state with unique soil types and climatic factors. Some day we may discover them and when that happens, we’ll have to draw more lines in the sand.

BE: Do you think there are identifiable sub-regions within the Yadkin Valley appellation?

SS: Yes, as I mentioned before, I believe that other AVAs will most likely be discovered in our state. I think sub-regions will also follow. A good example is the Swan Creek area within the Yadkin Valley which is currently in petition.

BE: In the early years, French American hybrids such as Seyval Blanc and Chambourcin were the focus for growers. When did Vinifera come to dominate in the Yadkin, and how did that come about?

SS: I think the Yadkin Valley has the potential to grow many different varieties, which would give us diversity. It's a new appellation. We now know that the soils and climate are appropriate to grow Vitis vinifera, which at one time was thought to be impossible.

Most of the newer plantings and wineries followed the Westbend trend. Vinifera has always been more desirable with wine drinkers or consumers. Planting unknown varieties was risky when it came to marketing so the Vinifera started dominating in the Valley in the late 90’s. Most new plantings now contain some hybrids and so did many of the older plantings. Growers and wineries plant them as an insurance policy in case of disaster. The hybrids are definitely more resilient. Seyval Blanc and Chambourcin used to be the most widely planted varieties but you now see Vidal Blanc, Chardonel and

Most of the newer plantings and wineries followed the Westbend trend. Vinifera has always been more desirable with wine drinkers or consumers. Planting unknown varieties was risky when it came to marketing so the Vinifera started dominating in the Valley in the late 90’s. Most new plantings now contain some hybrids and so did many of the older plantings. Growers and wineries plant them as an insurance policy in case of disaster. The hybrids are definitely more resilient. Seyval Blanc and Chambourcin used to be the most widely planted varieties but you now see Vidal Blanc, Chardonel and

Steve Shepard (SS): After finishing college in 1984, I had completed an apprentice program in Pennsylvania and moved on to another winery in the state. In 1989, after 5 years at Shuster Cellars, I had the opportunity to move to North Carolina to help start Westbend Vineyards. After seeing what Virginia was doing, I felt that the climate in North Carolina was more appropriate to growing vinifera Westbend was actually pioneering the wine industry in the entire state, and they were making great strides in the vineyards with Vinifera. I worked over 10 years at Westbend, before moving on to RayLen in 2000. At Westbend we were in the middle of what would become the Yadkin Valley AVA.

BE: The Yadkin Valley is North Carolina's first AVA. As one of the earliest winemakers in this appellation, what characteristics have you seen evolve that are particular to this region?

BE: The Yadkin Valley is North Carolina's first AVA. As one of the earliest winemakers in this appellation, what characteristics have you seen evolve that are particular to this region? SS: The quality and characteristics of the wine have evolved in the Yadkin Valley over the past several years largely because of the increase in the number of wineries. This area has not shown its best yet, but it is only a matter of time.

One of the exciting developments is that many new growers are experimenting with varieties other than the traditional Chardonnay, Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon. Growers are planting Italian and Spanish varieties as well. In the next 10 years, we’ll gradually learn what varieties are best suited for particular sites.

BE: What were the main criteria used to delineate Yadkin Valley as an appellation?

SS: The Yadkin Valley is an area that follows the contour of the Yadkin River. The elevation is a significant aspect of the region, ranging from about 1300 feet down to around 700 feet. This seems to provide the proper climatic conditions for wine grape growing in our region. The winters are not extreme but yet we observe temperatures in the teens overnight which help minimize fungus spores, insect populations and possibly Pierce's disease. Springtime normally brings ample rainfall. Our summers are usually hot and dry which drives sugar to optimum levels. The cool nights traditionally don’t start until September so later varieties (red varieties) benefit from this aspect. All in all, the growing season is long so that the vines have plenty of time to harden off even after harvest. This contributes to the health of vine for a month and a half or two before frost so that vines can slowly acclimate to cooler temperatures after harvest.

The soils vary from higher to lower elevations. The higher elevations tend to have higher percentages of organic matter contained in heavier clay. Clay soils have a greater moisture holding capacity, so during a long dry summer, vines will thrive. Some of the better vineyard sites are on slopes, so if heavy rains occur in the late summer, most of the water runs off. Some vineyards have tried to plant close to the river where the soils are sandy with silt and very well drained, but spring frost can be the worst enemy on these sites.

BE: Has a greater understanding of the terroir of Yadkin led to changes in viticultural practices since you came here? I’m thinking of the trellising systems, for instance.

SS: Vertical shoot positioning or VSP has mostly been the system of choice. The open lyre system is showing up at various locations and it is proving to be the better choice on vigorous sites. The main change in viticultural practice is that trellis systems, whatever they may be, are more professionally installed. Many vineyards in the past used old locust trees or cedar trees for post. Minimal fixed wires (1-3 total) were used whereas now several catch wires (2-3 sets) that are movable during the growing season along with fruiting wires are being used.

SS: Vertical shoot positioning or VSP has mostly been the system of choice. The open lyre system is showing up at various locations and it is proving to be the better choice on vigorous sites. The main change in viticultural practice is that trellis systems, whatever they may be, are more professionally installed. Many vineyards in the past used old locust trees or cedar trees for post. Minimal fixed wires (1-3 total) were used whereas now several catch wires (2-3 sets) that are movable during the growing season along with fruiting wires are being used.Another development is that many new growers are installing irrigation in the first year. Hedging is becoming normal practice as well.

BE: Do you believe the appellation's designated boundaries are valid and meaningful? Do they need to be revised?

SS: The designated boundaries are based on topographic and geological research. When it comes to drawing a line in the sand you have to choose a spot. The original proposed boundaries have been revised to extend further south along the river basin. The boundaries must be valid and meaningful or they would not be there. I feel that there are other potential appellations in our state with unique soil types and climatic factors. Some day we may discover them and when that happens, we’ll have to draw more lines in the sand.

BE: Do you think there are identifiable sub-regions within the Yadkin Valley appellation?

SS: Yes, as I mentioned before, I believe that other AVAs will most likely be discovered in our state. I think sub-regions will also follow. A good example is the Swan Creek area within the Yadkin Valley which is currently in petition.

BE: In the early years, French American hybrids such as Seyval Blanc and Chambourcin were the focus for growers. When did Vinifera come to dominate in the Yadkin, and how did that come about?

SS: I think the Yadkin Valley has the potential to grow many different varieties, which would give us diversity. It's a new appellation. We now know that the soils and climate are appropriate to grow Vitis vinifera, which at one time was thought to be impossible.

Most of the newer plantings and wineries followed the Westbend trend. Vinifera has always been more desirable with wine drinkers or consumers. Planting unknown varieties was risky when it came to marketing so the Vinifera started dominating in the Valley in the late 90’s. Most new plantings now contain some hybrids and so did many of the older plantings. Growers and wineries plant them as an insurance policy in case of disaster. The hybrids are definitely more resilient. Seyval Blanc and Chambourcin used to be the most widely planted varieties but you now see Vidal Blanc, Chardonel and

Most of the newer plantings and wineries followed the Westbend trend. Vinifera has always been more desirable with wine drinkers or consumers. Planting unknown varieties was risky when it came to marketing so the Vinifera started dominating in the Valley in the late 90’s. Most new plantings now contain some hybrids and so did many of the older plantings. Growers and wineries plant them as an insurance policy in case of disaster. The hybrids are definitely more resilient. Seyval Blanc and Chambourcin used to be the most widely planted varieties but you now see Vidal Blanc, Chardonel and

Print this article | Email this article | More about Yadkin Valley | More from Barbara Ensrud