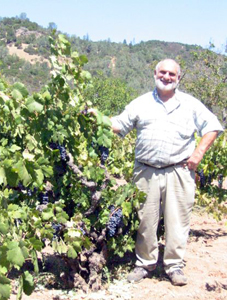

Jim Frediani and Clarence Luvisi tend their top dollar vines the old fashioned way.

Nothing New About the Success of These Old Napa Vineyards

Jim Frediani and Clarence Luvisi are two Calistoga grape growers who command some of the highest prices for their fruit, which is sourced from vines that date as far back as 100 years. How do they do it? As Alan Goldfarb found out, it's the good old-fashioned way.

by

Alan Goldfarb

October 22, 2007

nlike most of today’s vineyard managers who use the latest sophisticated techniques to monitor what’s going on, first cousins Clarence Luvisi and Jim Frediani seem to operate viscerally and through empirical knowledge; but they are no less informed.

nlike most of today’s vineyard managers who use the latest sophisticated techniques to monitor what’s going on, first cousins Clarence Luvisi and Jim Frediani seem to operate viscerally and through empirical knowledge; but they are no less informed.

“You could say I’m a Luddite, but this is my life,” Frediani replies when it’s observed that he doesn’t seem to have anything written on paper. “Some people have careers and they retire. I’ll work until I expire. This is what I thought farming was all about.”

Adds his cousin, “In today’s world, a lot of your grape growers are technically savvy. I don’t socialize with a lot of people but I pay attention to what I see in the soils. You pay attention to the vines.”

“And you hope you remember it,” Frediani concludes his thought.

Jim Frediani with Carignane vines which date back to 1953.

The oldest vines – Zinfandel, Carignane, Valdigue (Napa Gamay), Petite Sirah, and Charbono – go back to 1935 although Frediani says he doesn’t believe the county records which say they were first planted in 1920.

Those varieties, plus Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot,Cabernet Franc, Syrah, Grenache, Pinot Meunier, and Sauvignon Blanc are highly prized and coveted by more than 20 producers, who consider them to be some of the most intense valley floor grapes in the Napa Valley.

From Frediani’s 130 acres, such wineries as Caymus, Duxoup, Etude, Martini, Saddleback, Stag’s Leap Winery, T-Vine and Selene buy grapes, paying anywhere from $1,800 to $5,400 a ton. Across the narrow, dusty road immediately to the north, Etude, Ravenswood, SLW, Signorello and Cosentino source grapes from Luvisi’s 27 acres for which they pay up to $4,500.

The flat Frediani and Luvisi vineyards – located in the middle of the valley - have four different soil types and cool breezes. But Luvisi points out Calistoga’s vineyards are hotter than those down-valley in St. Helena and Yountville.

But Frediani reminds, “We can be cooler.”

Everything is NOT Up To Date in Calistoga

But not all is copasetic in Calistoga. Aside from the region being stymied in its effort to gain AVA (American Viticultural Area) status due to two brands with Calistoga geographical names, a certain percentage of the region’s soils are just not conducive to growing wine grapes.That’s because of a mineral called boron, which in high doses kills grapevines; and in Calistoga, especially north of the city, boron is prevalent. Although it’s precisely what lends a hand in geothermal water which gave rise to the area’s famous hot springs, boron is an anathema to growing grapes. One must, therefore, tread cautiously when planting a vineyard.

Even Frediani and Luvisi’s parcels, located south of the town, have some of the element interspersed throughout their vineyards and thus there are areas where no vines survive. Which leads Frediani to call Calistoga’s terroir, with a hearty laugh, "Hot, old Calistoga."

Luvisi calls the region’s water table “unique,” but he points out, there’s a solid rock layer and clay layer which makes the difference between potable water and geothermal; and one has to have those layers in order to avoid boron. “But,” he concedes “the soil is warmer.” Although he’s quick to caution, “It’s a question.

Clarence Luvisi points out Zinfandel vines he says were planted in 1908.

Around the geysers? Forget about it. Frediani chimes in, “Someone once said, boron’s good for nothing, but asparagus.”

Nonetheless, there are some great vineyards in Calistoga and Luvisi and Frediani sit on top of two of them. Their immediate neighbors are the famed Araujo Eisele Vineyard and the vineyards of Sterling and Fisher.

Frediani and Luvisi’s vineyards are older, and in some circles, their grapes are sought more for their old-world growing methods and intensity of flavors. Being the stewards of such grapevines, what does this duo think of the notion of so-called “old vine” grapes?

“To me, ‘old vine’ is before 1960,” says Frediani, “but mine are older than that, going back to the nineteen-forties and certainly before 1950. As you get older though, ‘old’ is a relative term.”

His older cousin is more cautionary. “Buyer beware!” he warns. “It’s a nice marketing tool, but you can’t plant a 100-year-old vineyard.”

In their old vineyards, Jim Frediani and Clarence Luvisi – despite the perception of their anti-technocratic stance - most certainly have to acquiesce to modernity – or do they? “I never used to do leaf removal (in order to allow more sunlight to the grapes). I never did that when my dad was alive,” responds Frediani, whose father Eugene died in 1978.

Luvisi says he’s given in “somewhat.” Over the last 10 or 15 years, he’s installed drip systems, started replanting, changed his spacing and trellising regimens and now does second-crop thinning and pruning. And, as you might expect, modern techniques practiced by these two are, well, not so much.

“I don’t” practice modern grape growing, Frediani declares. “I don’t go in for things like pressure bombs (a device that measures water stress of vines in order to monitor irrigation needs). I’m not into the current vogue trends. Fortunately, I didn’t plant AXR (the rootstock that was fashionable in the ‘80s which was susceptible to vine-destroying phylloxera).”

On this hot summ

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,

READER FEEDBACK: To post your comments on this story,