Long Island Correspondent Lenn Thompson rejoices in pink.

Halleluiah! -- The Rosé Revival

It has never been so en vogue to drink pink. Fittingly in a state known for setting trends, the winemakers of Long Island are fashioning classic dry rosé from star varietals such as Merlot, Cabernet Franc and Cabernet Sauvignon. These classic barbeque wines will never be looked at the same way again.

by

Lenn Thompson

July 25, 2006

Call it blush, vin gris or just plain "pink" if you want, but rosé is back. And local winemakers — and wine lovers — are rejoicing the revival of these underappreciated and misunderstood wines.

It could be argued rosé never really left. White Zinfandel, the most well known pink wine this side of France, is made and sold by the lake full. But while Zinfandel is the most-used grape for pink wines in California, grapes like Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc dominate Long Island's rosé scene.

It could be argued rosé never really left. White Zinfandel, the most well known pink wine this side of France, is made and sold by the lake full. But while Zinfandel is the most-used grape for pink wines in California, grapes like Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc dominate Long Island's rosé scene.

The sugary sweet style popularized by California White Zin isn't all there is in the pink wine realm, however. In fact, those grown up versions of kool-aid bear little resemblance to the always dry, often bold and interesting rosé wines of Provence and Anjou. White Zin is just one of the many versions being made today and there are as many styles as there are shades of pink.

So why is rosé on the comeback trail — across the country and on Long Island?

Wine consumption is on the rise. Wine has passed beer as the most popular alcoholic beverage in America. More people drinking wine means more people drinking rosé — most likely because it's easy to drink for those who are new to wine.

According to Kareem Massoud from Paumanok Vineyards there is more to it, "more and more Americans are drinking 'premium' wines, having graduated from inexpensive jug wines and wine coolers — to more complex yet easy-to-drink wines such as Pinot Grigio, Merlot, Chardonnay, Riesling and rosé."

Bedell Cellars' Trent Preszler agrees, saying "rosé's popularity might be the result of increased consumer appreciation of the dry, classic style. There are more producers now making dry, elegantly structured rosés that are a departure from some people's perceptions."

Rosé is also a terrific alternative to white wine for red wine lovers as well, making it an ideal summertime sipper. Well-made rosé combines the complexity and structure of red wine with the refreshing, thirst quenching qualities of whites. In the late afternoon, Theresa Dilworth, co-owner and winemaker for Comtesse Therese, likes to drink a chilled rosé – especially while she's cooking dinner. Says Therese, "it is refreshing, and I usually prefer it to white wine. I usually drink red wine later, with dinner."

Rosé is also incredibly versatile for gourmands. Did you just buy some fresh fish from our local waters? Rosé will complement them well. Serving smoky-sweet barbequed chicken and burgers? It works there too. You can even serve rosé with a steak.

Christopher Tracy, a former chef and the current winemaker at Channing Daughters Winery loves rosé because "no other wine style, red or white, offers so many options at the table. The old adage is rosé pairs well with (everything from) seafood to steak. It's not only comfortable with a variety of foods, but dry rosé is happy on a checkered picnic table or a four star white linen table cloth. Rosé can be casual and serious at the same time. We drink everything with rosé, the foods just change with the seasons. Our favorites include raw bar, spring vegetable frittatas, tomatoes and mozzarella, charcuterie, almost anything off the grill, cheese, stuffed squash blossoms, roasted turkey and chicken. We also love dry rosé because it is easy, delicious, beautiful to look at and just plain fun."

There are two main ways to make rosé. The first and most traditional is the saignée method. Saignée means “to bleed” and it involves draining off some of the red wine juice to increase the skin-to-juice ratio during the red wine making process – making the red wines more concentrated and flavorful. The juice that is ‘bled’ off is used to make rosé.

The second method is used when rosé wine is the primary goal. Red wine grapes are crushed and the skins are allowed to remain in contact with the juice for only a short time. The grapes are then pressed, and the skins are discarded rather than left in contact throughout fermentation as with red wine making. Because the skins contain much of the flavor and color compounds, this leaves the wine tasting more similar to a white wine and looking pink rather than red. In both methods, although not traditional, some white grape juice may be added before fermentation — usually to bring added acidity and vibrance.

No matter the method, rosé is rarely, if ever, the focus for any winery. They aren't necessarily afterthoughts, but few wineries set out to make a truly spectacular rosé – instead producing them to improve their red wines, round out their portfolios and/or meet consumer demand.

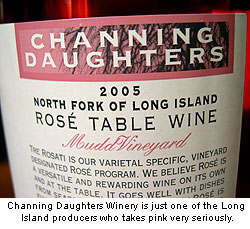

Two Long Island wineries, however, recognize rosé’s potential are taking the lead in moving beyond rosé as a postscript.

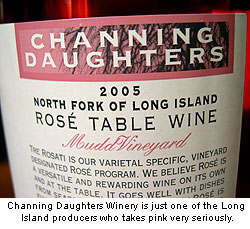

Channing Daughters Winery has a reputation for being experimental and trying new things. While most Long Island wineries focus on Bordeaux varieties, Channing Daughters thinks the region more closely resembles Northern Italy. They also grow unique-to-Long Island varieties like Tocai Friulano, Muscat Ottonel and and Aligoté.

Channing Daughters Winery has a reputation for being experimental and trying new things. While most Long Island wineries focus on Bordeaux varieties, Channing Daughters thinks the region more closely resembles Northern Italy. They also grow unique-to-Long Island varieties like Tocai Friulano, Muscat Ottonel and and Aligoté.

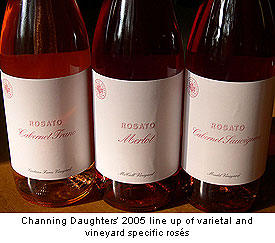

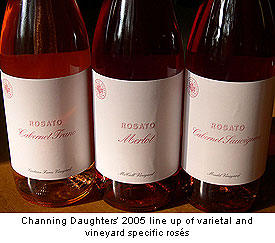

Now, with the 2005 vintage, they've introduced their Tre Rosati (three rosé) – a line of vineyard and variety specific rosés. They have produced three rosés in 2005 – the 2005 Rosati di Cabernet Franc from the Croteau Farm Vineyard, the 2005 Rosati di Merlot from the McCall Vineyard and the 2005 Rosati di Cabernet Sauvignon from the Mudd Vineyard.

"We wanted to take rosé to the next level in our region. We wanted to put rosé on the forefront. We want to celebrate rosé, especially with the bounty of the ocean, the bays and the land where we grow our grapes and make our wine. We like to encourage specificity and individuality so a vineyard-designated, varietal-specific rosé program just made sense." Tracy said, adding "we also wanted to show ourselves and our customers the range of expression that dry rosati can have. Each one offers a different experience and varied opportunity for food pairings."

At Shinn Estate Vineyards on the

It could be argued rosé never really left. White Zinfandel, the most well known pink wine this side of France, is made and sold by the lake full. But while Zinfandel is the most-used grape for pink wines in California, grapes like Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc dominate Long Island's rosé scene.

It could be argued rosé never really left. White Zinfandel, the most well known pink wine this side of France, is made and sold by the lake full. But while Zinfandel is the most-used grape for pink wines in California, grapes like Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc dominate Long Island's rosé scene.The sugary sweet style popularized by California White Zin isn't all there is in the pink wine realm, however. In fact, those grown up versions of kool-aid bear little resemblance to the always dry, often bold and interesting rosé wines of Provence and Anjou. White Zin is just one of the many versions being made today and there are as many styles as there are shades of pink.

So why is rosé on the comeback trail — across the country and on Long Island?

Wine consumption is on the rise. Wine has passed beer as the most popular alcoholic beverage in America. More people drinking wine means more people drinking rosé — most likely because it's easy to drink for those who are new to wine.

According to Kareem Massoud from Paumanok Vineyards there is more to it, "more and more Americans are drinking 'premium' wines, having graduated from inexpensive jug wines and wine coolers — to more complex yet easy-to-drink wines such as Pinot Grigio, Merlot, Chardonnay, Riesling and rosé."

Bedell Cellars' Trent Preszler agrees, saying "rosé's popularity might be the result of increased consumer appreciation of the dry, classic style. There are more producers now making dry, elegantly structured rosés that are a departure from some people's perceptions."

Rosé is also a terrific alternative to white wine for red wine lovers as well, making it an ideal summertime sipper. Well-made rosé combines the complexity and structure of red wine with the refreshing, thirst quenching qualities of whites. In the late afternoon, Theresa Dilworth, co-owner and winemaker for Comtesse Therese, likes to drink a chilled rosé – especially while she's cooking dinner. Says Therese, "it is refreshing, and I usually prefer it to white wine. I usually drink red wine later, with dinner."

Rosé is also incredibly versatile for gourmands. Did you just buy some fresh fish from our local waters? Rosé will complement them well. Serving smoky-sweet barbequed chicken and burgers? It works there too. You can even serve rosé with a steak.

Christopher Tracy, a former chef and the current winemaker at Channing Daughters Winery loves rosé because "no other wine style, red or white, offers so many options at the table. The old adage is rosé pairs well with (everything from) seafood to steak. It's not only comfortable with a variety of foods, but dry rosé is happy on a checkered picnic table or a four star white linen table cloth. Rosé can be casual and serious at the same time. We drink everything with rosé, the foods just change with the seasons. Our favorites include raw bar, spring vegetable frittatas, tomatoes and mozzarella, charcuterie, almost anything off the grill, cheese, stuffed squash blossoms, roasted turkey and chicken. We also love dry rosé because it is easy, delicious, beautiful to look at and just plain fun."

There are two main ways to make rosé. The first and most traditional is the saignée method. Saignée means “to bleed” and it involves draining off some of the red wine juice to increase the skin-to-juice ratio during the red wine making process – making the red wines more concentrated and flavorful. The juice that is ‘bled’ off is used to make rosé.

The second method is used when rosé wine is the primary goal. Red wine grapes are crushed and the skins are allowed to remain in contact with the juice for only a short time. The grapes are then pressed, and the skins are discarded rather than left in contact throughout fermentation as with red wine making. Because the skins contain much of the flavor and color compounds, this leaves the wine tasting more similar to a white wine and looking pink rather than red. In both methods, although not traditional, some white grape juice may be added before fermentation — usually to bring added acidity and vibrance.

No matter the method, rosé is rarely, if ever, the focus for any winery. They aren't necessarily afterthoughts, but few wineries set out to make a truly spectacular rosé – instead producing them to improve their red wines, round out their portfolios and/or meet consumer demand.

Two Long Island wineries, however, recognize rosé’s potential are taking the lead in moving beyond rosé as a postscript.

Channing Daughters Winery has a reputation for being experimental and trying new things. While most Long Island wineries focus on Bordeaux varieties, Channing Daughters thinks the region more closely resembles Northern Italy. They also grow unique-to-Long Island varieties like Tocai Friulano, Muscat Ottonel and and Aligoté.

Channing Daughters Winery has a reputation for being experimental and trying new things. While most Long Island wineries focus on Bordeaux varieties, Channing Daughters thinks the region more closely resembles Northern Italy. They also grow unique-to-Long Island varieties like Tocai Friulano, Muscat Ottonel and and Aligoté. Now, with the 2005 vintage, they've introduced their Tre Rosati (three rosé) – a line of vineyard and variety specific rosés. They have produced three rosés in 2005 – the 2005 Rosati di Cabernet Franc from the Croteau Farm Vineyard, the 2005 Rosati di Merlot from the McCall Vineyard and the 2005 Rosati di Cabernet Sauvignon from the Mudd Vineyard.

"We wanted to take rosé to the next level in our region. We wanted to put rosé on the forefront. We want to celebrate rosé, especially with the bounty of the ocean, the bays and the land where we grow our grapes and make our wine. We like to encourage specificity and individuality so a vineyard-designated, varietal-specific rosé program just made sense." Tracy said, adding "we also wanted to show ourselves and our customers the range of expression that dry rosati can have. Each one offers a different experience and varied opportunity for food pairings."

At Shinn Estate Vineyards on the

Print this article | Email this article | More about Long Island | More from Lenn Thompson